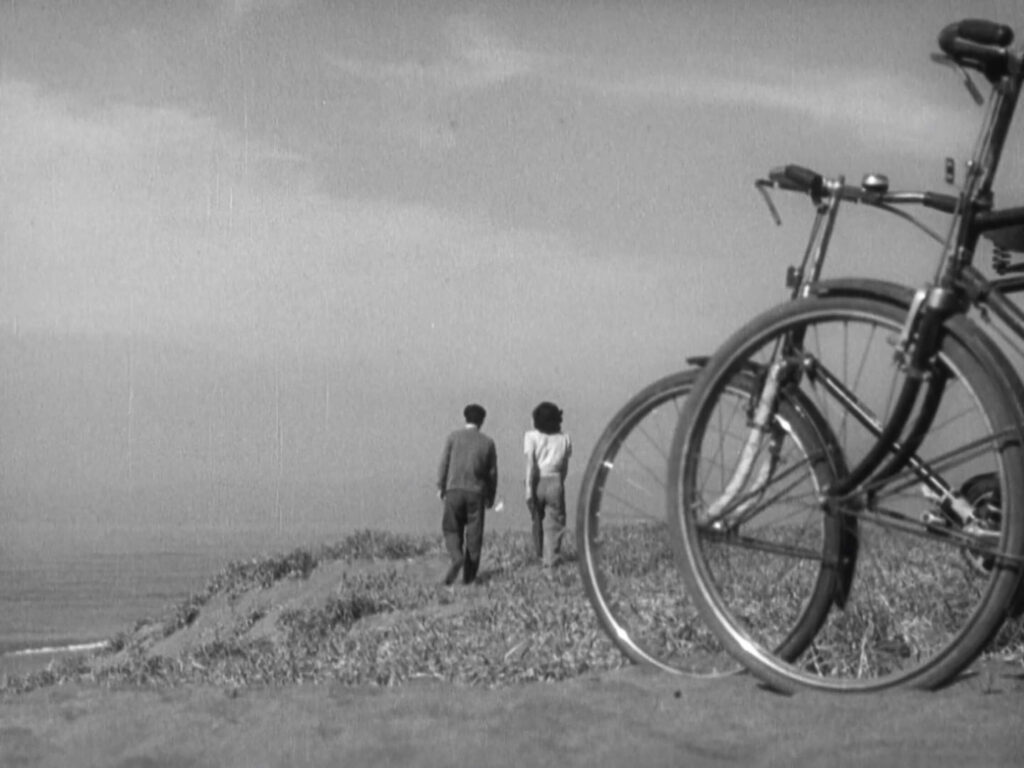

Late Autumn (1960)

Overshadowed it may be compared to Yasujirō Ozu’s other family dramas, but Late Autumn’s examination of marriage and remarriage in mid-century Japan still finds fresh emotional textures in its colour cinematography, intertwining love, duty, and generational bonds.