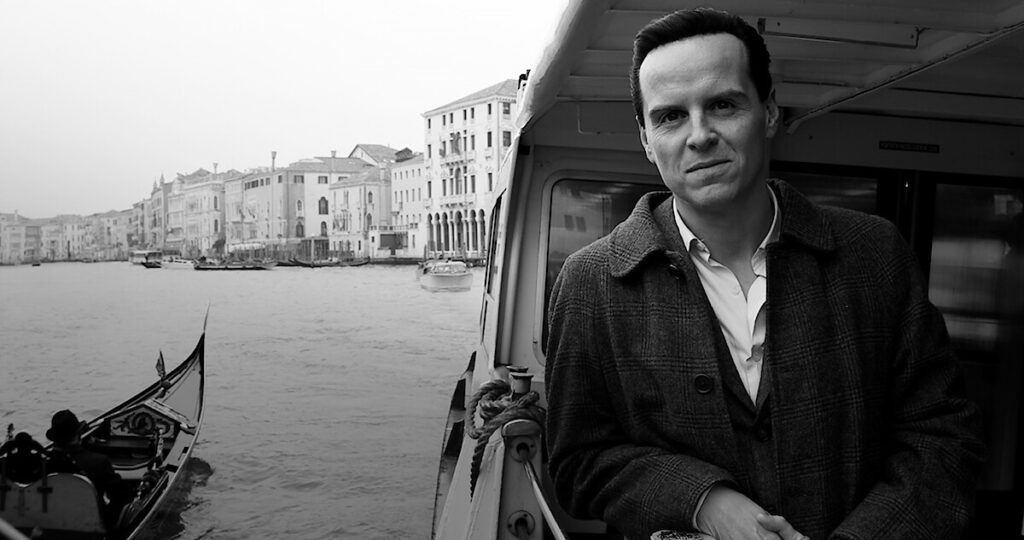

Brothers and Sisters of the Toda Family (1941)

When the patriarch of one affluent family is lost in Brothers and Sisters of the Toda Family, there is little left to hold its fragmented remains together, and Yasujirō Ozu exacts a cutting critique of those intimate bonds weakened by class privilege.