Coralie Fargeat | 2hr 20min

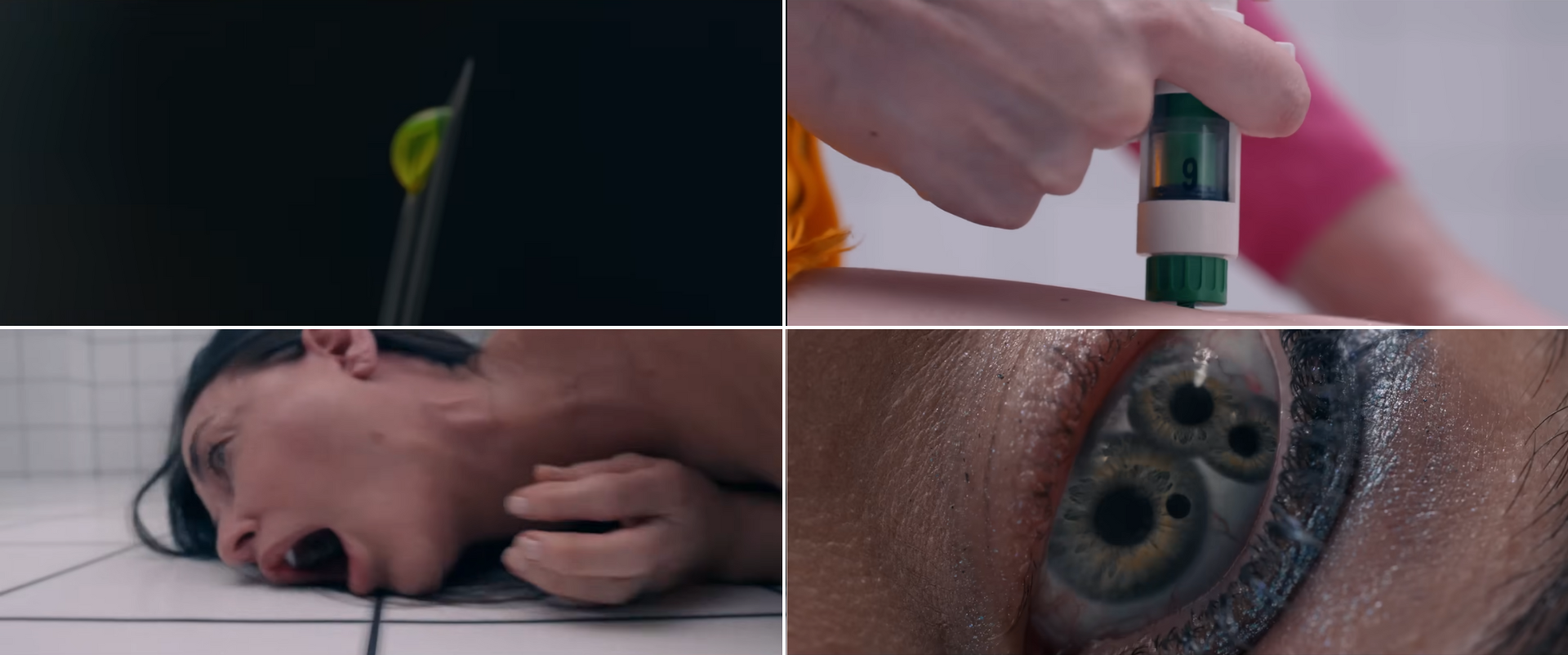

The first time that fading Hollywood actress Elisabeth Sparkle injects the fluorescent, black-market drug that is the Substance, her metamorphosis is shocking. As she writhes in agony on her bathroom floor, her skin bulges with the birth of new bones and organs, and her irises split like regenerating cells. Along her back, a large, gaping slit opens, and from it a creature is born. Stumbling towards the mirror, we adopt this newborn’s perspective, our eyes adjusting to its bizarre existence. There, we witness Elisabeth’s younger, more beautiful self ‘Sue’ come into focus, successfully reclaiming youth from the wrinkles, sags, and insecurities of middle age.

There are several caveats which come with the use of this drug, chief among them being the time limit – seven days in the young body, seven days in old, or else there will be severe side effects. “What is taken by one, is lost by the other,” we are frequently reminded by the distributor’s deep, disembodied voice, and upon this simple warning, director Coralie Fargeat builds her allegory for the physical deterioration of ageing bodies. Any attempts to recklessly cling to youth will inevitably be felt further down the track, forming destructive, self-loathing habits which give our younger selves greater reason to scorn us.

The Substance is not overly subtle in its metaphor, nor does it need to be. Elisabeth lives in a cartoonish mirror world of 1980s pop aesthetics and old-fashioned chauvinism, working closely with a sleazy producer who embodies every misogynistic stereotype of America’s entertainment industry. He leers uncomfortably over us in wide-angle lenses, physically invading our personal space and tearing into a bowl of prawns with all the etiquette of a salivating dog. His firing of our protagonist and subsequent casting call for “the next Elisabeth Sparkle” only feeds her self-doubt – but with this rejuvenating drug on the market, who better to take her place than Elisabeth herself?

Contrary to what Fargeat’s win for Best Screenplay at Cannes Film Festival may suggest, the writing may be the least interesting aspect of The Substance. This is not to say that it lacks a compelling narrative, but the strength of this psychological horror bleeds through the visual storytelling, often carried along without dialogue by the dynamic editing, subjective camerawork, and brilliantly unhinged acting. Especially for industry veteran Demi Moore and rising star Margaret Qualley, The Substance displays both of their strongest performances to date, playing two sides of one woman simultaneously envying and revelling in her youthful glamour.

Fargeat too clearly has an admiration for the human form, though her camera refuses to submit so cleanly to the objectification it is criticising. The allure and repulsiveness of our physical bodies are woven deeply into each other here, and as Elisabeth comes to realise, we cannot indulge in one without eventually confronting the other. Extreme close-ups of dissolving tablets, needles puncturing flesh, and the Substance’s physiological effects blend seamlessly with the augmented sound design and distorted synth score, and their collective impact is largely magnified by Fargeat’s aggressive, rapid-fire montage editing. It is no coincidence that she is directly referencing Requiem for a Dream here, comparing the processes of beautification to an uncontrollable drug addiction. As much as the older Elisabeth despises her other half, still she is compelled to keep chasing that high of soaring confidence and attention, thus feeding the loop of self-abuse.

“You’re the only lovable part of me.”

The dual visual styles that The Substance establishes for both women draws a harsh dichotomy here. Where Sue luxuriates in smooth, slow-motion photography, Elisabeth’s shame is amplified by handheld camerawork and grating jump cuts, viciously wearing away at her mind and body. Bit by bit, we see pieces of both personalities bleed out into the world as well, alternately polishing and contaminating interiors designed to sanitised, Kubrickian perfection.

Just as several decades’ worth of Elisabeth’s posters are stripped from the film studio’s bright orange hallway to make room for its newest star, so too is her image torn down from the billboard outside her penthouse window, and ultimately replaced with a larger-than-life model shot of Sue. This apartment is the only remaining space that truly belongs to Elisabeth, and so much to the revulsion of her younger self, she believes it is hers to degrade into filth and chaos any way she pleases.

Still, as much as these women furiously complain to the drug distributor about each other, both are firmly reminded of their equal culpability for their afflictions – “Remember you are one.” Elisabeth’s single, withered finger that results from Sue’s first attempt to push the limits of the Substance is only the beginning as well, revealing the long-term effects of those poor choices we make when we are young.

The more Elisabeth transforms into a spiteful, grizzled hag, the more we are reminded of the Evil Queen in Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, jealously comparing her deteriorating beauty against a more youthful replacement. By the time The Substance reaches its final act too, Fargeat fully embraces these fable-like qualities, though not without a nauseating edge of dark, ironic humour. Where the body horror begins with Darren Aronofsky as its primary inspiration, it gradually mutates into Cronenbergian visions of grotesque monstrosities, rendered in practical effects that grow progressively more depraved.

The bookended return to Elisabeth’s star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame makes for a surprisingly poignant conclusion to The Substance, escaping the bloody chaos to mourn her dehumanisation, even if just for a fleeting moment. Self-acceptance is a rarity in this industry of extreme beauty standards, so the point at which it is fearlessly embraced reveals the slightest salvation within reaching distance of catastrophic disaster. For those so consumed by such superficial ideals though, perhaps the physical manifestation of one’s most hideous impulses is the only path to inner peace, tragically confining them to a hollow, obsessive existence where youth fades faster than it can ever be reclaimed.

The Substance is currently playing in cinemas.