Greg Kwedar | 1hr 47min

Prison inmate Divine G may not have committed the crime he was found guilty of, but the shame and atonement which Sing Sing interrogates has nothing to do with the eyes of the law. Not once do we even learn what the other incarcerated participants of Divine G’s theatre program did to wind up here. Their rehabilitation is purely a matter of the soul, placing each on the same level regardless of their past. “We’re here to become human again,” one of them explains to the troupe’s newest member, Divine Eye, justifying the playful whimsy with which they conduct themselves in this safe space. “To put on nice clothes and dance around and enjoy the things that is not in our reality.”

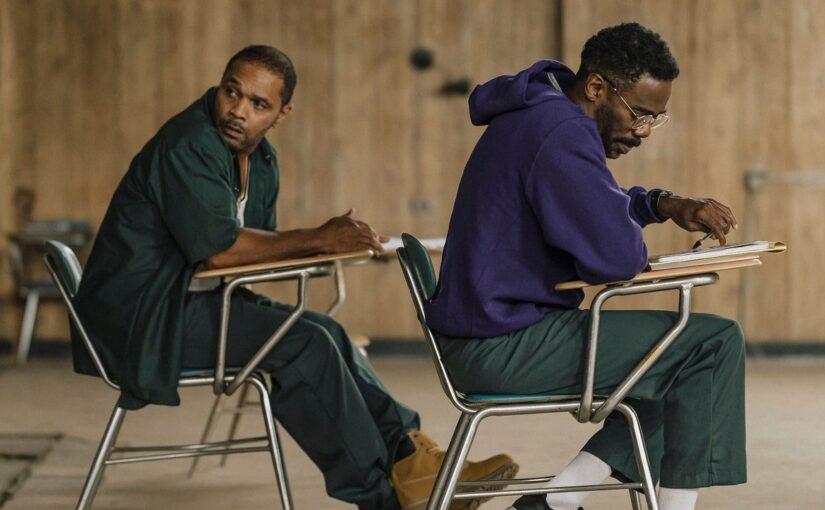

So sincere is Greg Kwedar in humanising these inmates that many are played by the actual men of the story this film is based on. Not only did the Rehabilitation Through the Arts program at Sing Sing Maximum Security Prison provide them a means of self-expression, a supportive community of fellow Black men, and a path forward – it also honed their talent enough for them to effectively fill in the ensemble of this character-driven prison drama. Through the act of performance, Divine G and his troupe find realer versions of themselves beyond a criminal record or their public infamy. Emotional wounds are revealed beneath outward displays of anger, and in the case of the kind, intelligent Divine G, flashes of bitterness escape his sensitive resolve.

Among the few professional actors in this cast, Colman Domingo leads Sing Sing with calm composure, acting as the unofficial leader of his troupe. When Divine G isn’t leading productions of Shakespeare, he is writing original scripts and modelling emotional maturity as a mentor for his fellow inmates. He passes no judgement, and neither do his fellow actors, until the arrival of Divine Eye threatens the community he has carefully cultivated. Their theatre exercises are goofy, Divine Eye remarks, and Divine G’s dreary dramas are far from exciting – so why not consider a zany time travel comedy for their next show?

While most of the troupe supportively rallies around Divine Eye’s suggestion, Divine G can’t help but feel threatened by this shifting power dynamic. His theatre group is his life, and Divine Eye’s inability to take any of this seriously cuts to his core. As such, the friction between both personalities takes centre stage in Sing Sing, with both Domingo and the real Divine Eye thoughtfully navigating a pair of intertwined character arcs. Kwedar does not fare so well in letting us feel the span of time spent with these men, but the bumpy road they travel towards a lifelong friendship is nevertheless a compelling one, seeing both step in for each other at different points when they are at their lowest.

For Divine G, this support is delivered through the conquest of his own ego, understanding Divine Eye’s desperate need for someone to help him articulate deeply buried emotions. Bit by bit, we see his development as an actor, bringing intonation to monologues rather than falling back on the anger and aloofness that he knows too well. For Divine Eye on the other hand, it is that newfound ability to relate with others which motivates him to reach out to his demoralised friend. After all Divine G’s hard work building the theatre group, we can feel his frustration when it is barely considered in his clemency hearing, and instead gives them ammunition for their harshest, most insulting question.

“So are you acting at all during this interview?”

That Divine G’s appeal should be rejected when Divine Eye is granted release seems totally unfair, and very gradually, we begin to see both men’s attitudes cross over. Where the mentor once guided the troublemaker into a welcoming community, he now rejects the brotherhood with biting resentment, broken by a system that is fundamentally rigged against Black people. Clearly Divine G is not immune to the repressed anger that so many of these incarcerated men reckon with, and the raw despair in Domingo’s performance makes for a particularly bleak contrast against his earlier self-assuredness. Nevertheless, the seeds that he spent years sowing into the community have finally sprouted, and in a rehabilitated Divine Eye, he finds his own compassion and wisdom reflected right back at him.

Each of these prisoners are fighting their own internal battles, and Divine G is no exception, learning to accept his place among peers despite his lawful innocence. What Kwedar lacks in visual style, he makes up for with delicate attention to character detail, demonstrating an inspired approach to casting which blurs truth and representation. Through this metafictional angle, Sing Sing merges its sensitive consideration of art’s healing power with its very form, producing a fresh, nuanced understanding of those disenfranchised by an institution specifically designed to break them down.

Sing Sing is coming soon to video on demand.