RaMell Ross | 2hr 20min

Not long after Black teenager Elwood begins at an internally segregated reform school, and after about forty minutes of looking at the world through his eyes, Nickel Boys shifts its first-person perspective. As a group of bullies mock him in the cafeteria, fellow student Turner quickly comes to his defence, beginning a friendship that will eventually become a lifeline for both during their time here. Before moving on though, RaMell Ross takes a leaf out of Ingmar Bergman’s Persona playbook and runs through the scene a second time, removing us from Elwood’s seat and placing us in Turner’s. For the first time, we see Elwood as a full being outside of reflections caught in shiny surfaces, granting us a fresh view of the world beyond his bright childhood and troubled adolescence.

From then on, Ross’s in-scene editing is freed up as he cuts between both points-of-view rather than sticking to long takes. On an even broader level though, his device also binds these boys within the film’s astonishing formal framework, presenting them as equal vessels through which we experience their growing disillusionment in a systematically racist institution. Nickel Boys may be Ross’ foray into narrative filmmaking, yet his avant-garde instincts come fully formed in his subjective camerawork and impressionistic montages, nostalgically slicing through memories that have been fragmented, reconstructed, and replayed in one’s mind a thousand times.

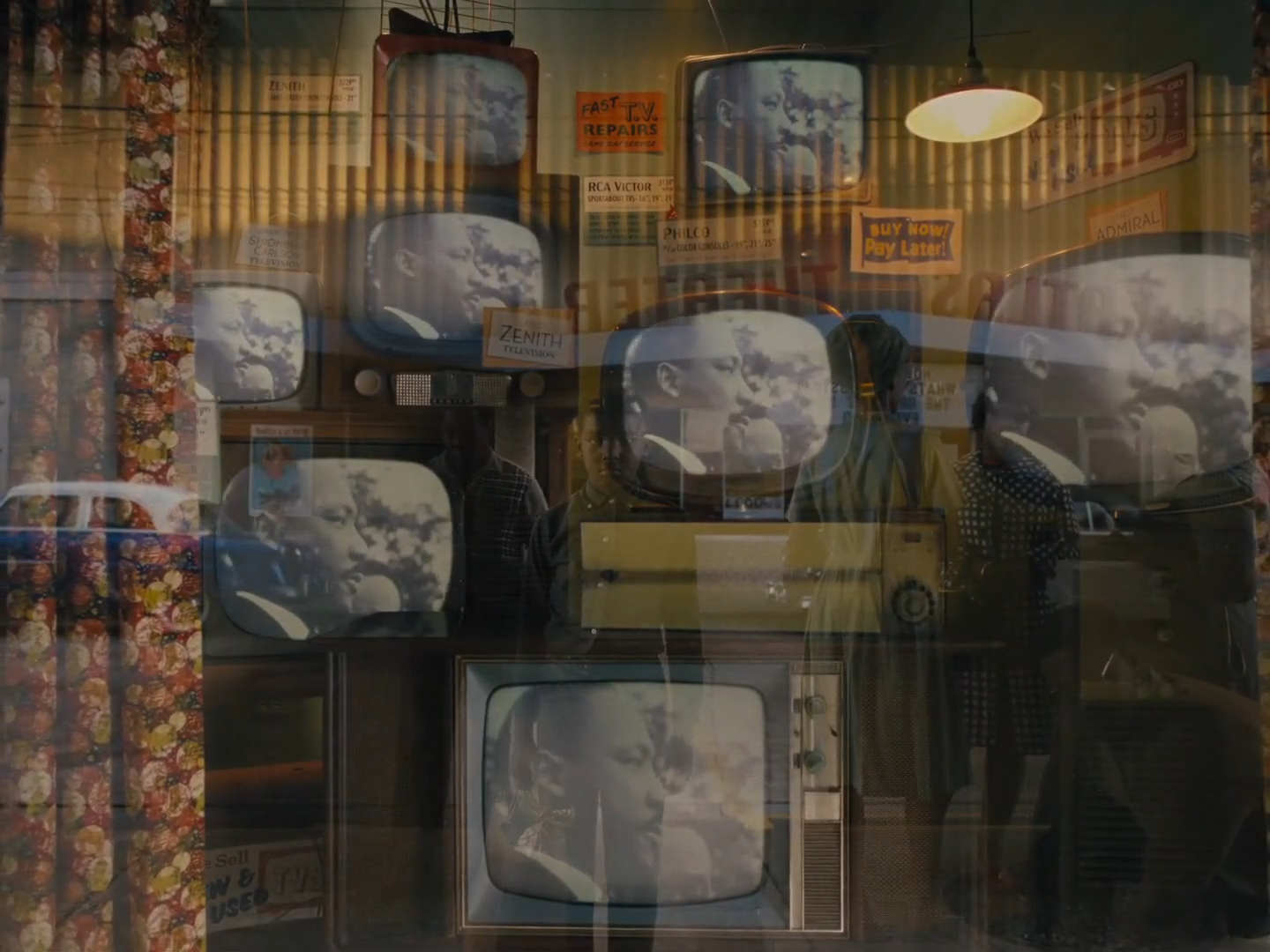

Monumental historic events are deeply tied to these recollections as well, not merely using the civil rights movement of 1960s America as a backdrop to Ross’ narrative, but as a gateway into his characters’ minds. As Martin Luther King Jr. speaks to enormous crowds on television screens, we catch a young Elwood watching through the shop window, absorbing a message which would later inspire his attempts to expose the abusive staff at Nickel Academy. Sidney Poitier films also engage his curious mind, while archival cutaways to the space race underscore the bitter irony between America’s grand ambition and the marginalisation of its most disadvantaged citizens. Within this context, the primary split between Elwood and Turner takes clear form – one being an idealistic advocate for social progress, and the other a cynic just looking to keep his head down.

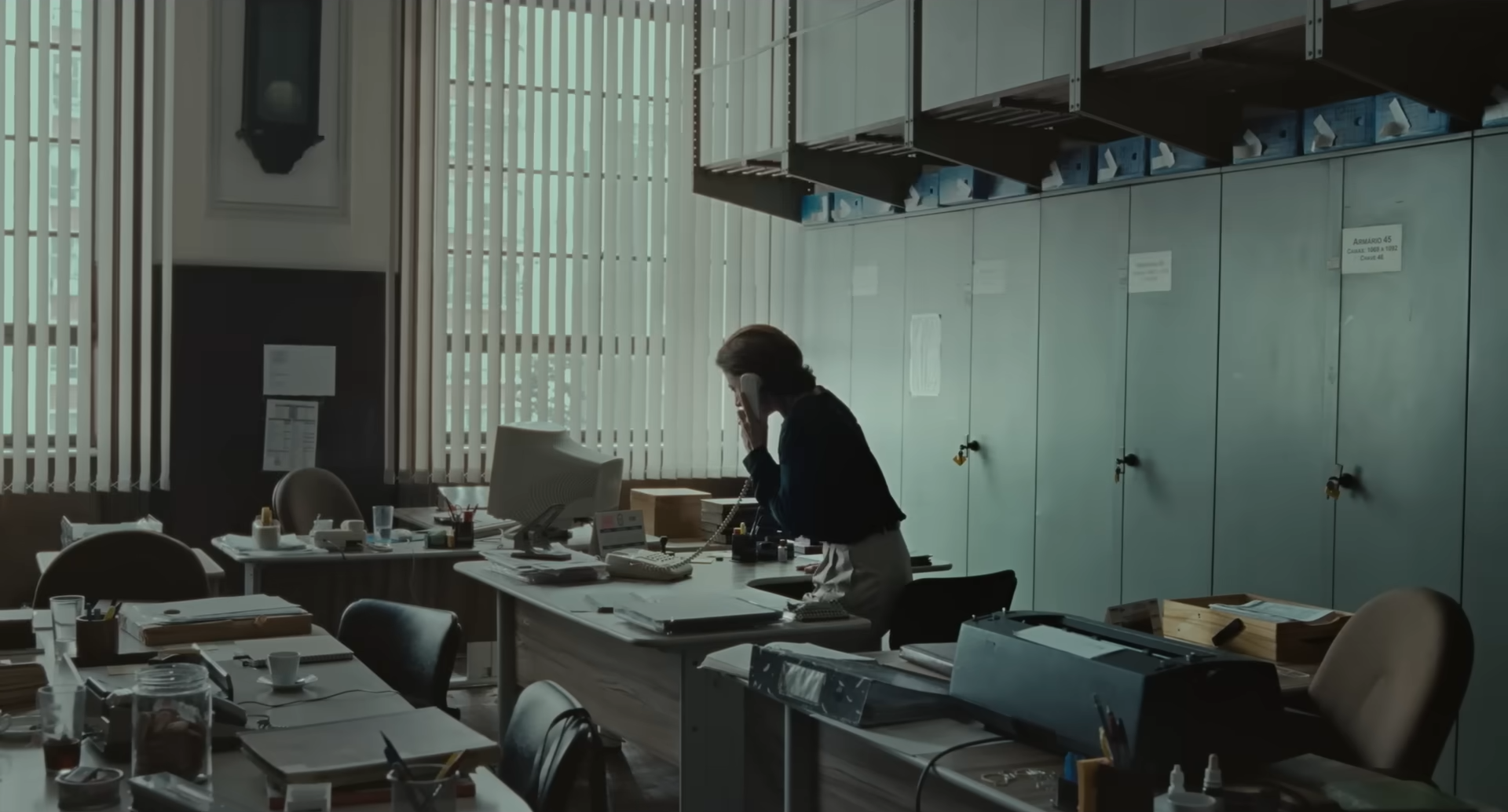

As such, it is fitting that Ross should ground the visual style of Nickel Boys in first-person perspectives, playing with camera angles, orientations, and movements that we are intimately familiar with in our own lives. During Elwood’s childhood, the camera stares up at towering environments and reveals his growing sense of self through reflective surfaces. When he lays on the ground, the whole world seems to shift around him too, and it isn’t uncommon for his gaze to drift off to other distractions mid-conversation.

Perhaps the most notable feature of this cinematic technique though is the abundant fourth wall breaks, seeing characters peer directly down the lens and invite us into their lives. What could easily be used as a gimmick instead melds beautifully with Ross’ evocative storytelling and cinematography, calling to mind László Nemes’ psychological dramas which hover the camera around his protagonists’ heads, and using similarly tight blocking of bodies and objects to crowd the frame. Striking an even closer comparison to Ross’ stylistic triumph here though is Barry Jenkins’ distinctive combination of shallow focus, close-ups, and direct eye contact, forging a profound connection with the ostracised subjects of his own films. That the dreamlike harmonies of this soulful score bear resemblance to If Beale Street Could Talk only deepens this likeness, and considering that both Nickel Boys and The Underground Railroad are based on novels by Colson Whitehead, it is evident that Ross and Jenkins inhabit a shared cinematic space.

Nevertheless, Ross’ style is very much his own, eroding our sense of linear time through abstract editing rhythms which flit through the past like old film reels and leap into the future with sober melancholy. The adult Elwood we meet in these flashforwards is far removed from the teenage boy living at Nickel Academy, as is Ross’ camera which hovers right behind his head rather than looking through his eyes. The effect is dissociating, recognising the lingering trauma which keeps him from moving forward despite his new start in New York City. All these decades later, he obsessively tracks news stories unearthing Nickel Academy’s sinister history, and watches fellow alumni come forward as witnesses to the abuse inflicted upon Black students. Perhaps the most affecting scene in this narrative strand though arrives during his run-in with former classmate Chickie Pete, where the buried torment of another ill-adjusted survivor is made painfully apparent in the subtext of what goes unsaid.

We can hardly blame these men for their instinctive psychological detachment though, especially given how much we are forced to suffer inside their minds with them. As several boys are woken in the middle of the night and forced to wait their turn in another room, Elwood’s gaze nervously lingers on a swinging lamp, the holy bible, his trembling leg – anything that might distract from the disturbing sounds behind that door he will soon be led through. At the very least, the reflection motif which permeates Ross’ mise-en-scène offers symbolic escapes from Elwood’s immediate reality, delivering one particularly astounding shot looking up at an overhead mirror as he and Turner discuss the prospect of fleeing the school for good.

Given the glimpses we are given of an adult Elwood, we feel assured that this freedom does indeed lie in his future, though the point where Ross connects both timelines makes for a formally staggering and heartbreaking transition. At the core of Nickel Boys’ first-person camera is the question of how one’s identity is formed from outside influences, and as such we see pieces of Elwood and Turner cling to each other, stoking both pragmatic caution and radical resolve. By minimising the display of outward expressions, Ross instead defines his characters by the indelible impressions they absorb from their volatile environments, internalising a shared, intrepid resilience that leads friends, communities, and an entire nation towards liberation.

Nickel Boys is currently streaming on Amazon Prime Video.