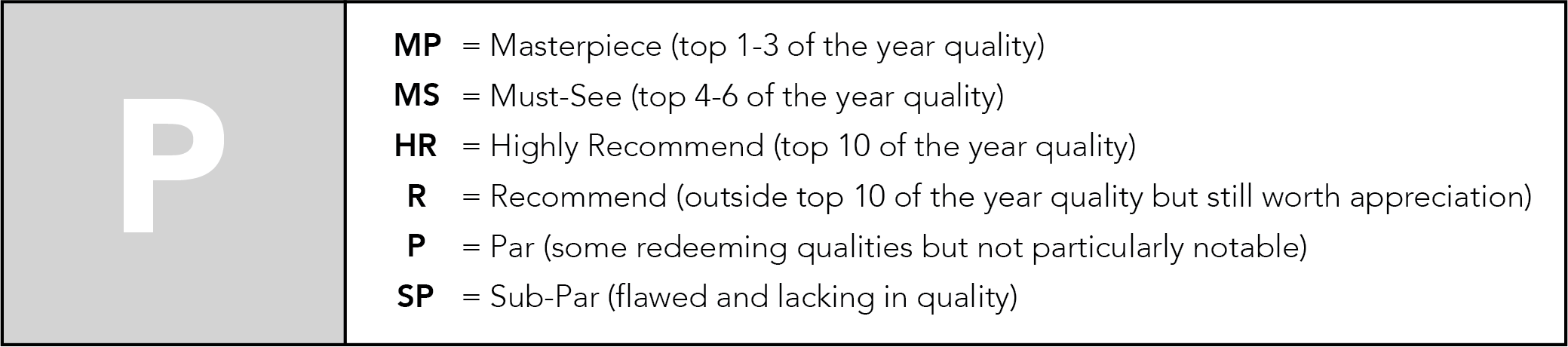

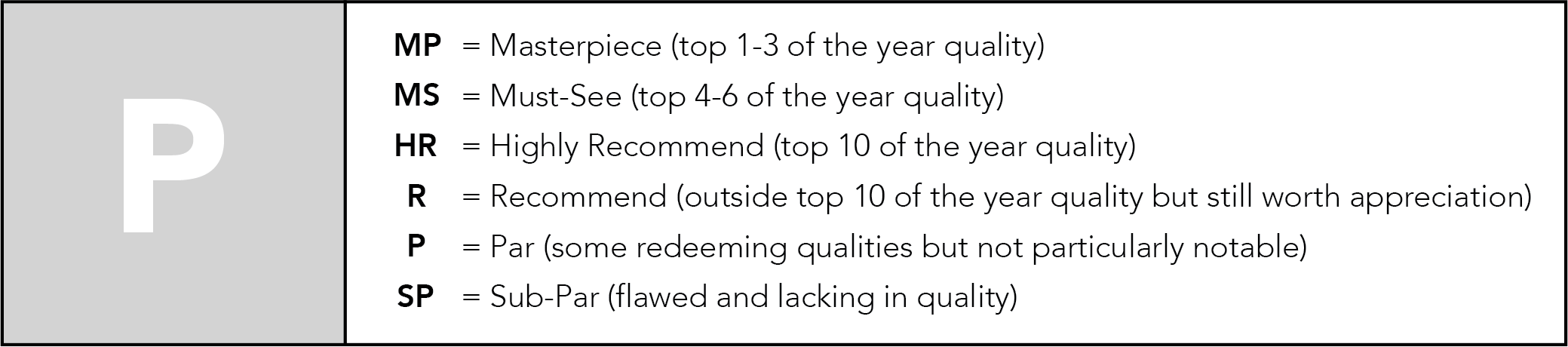

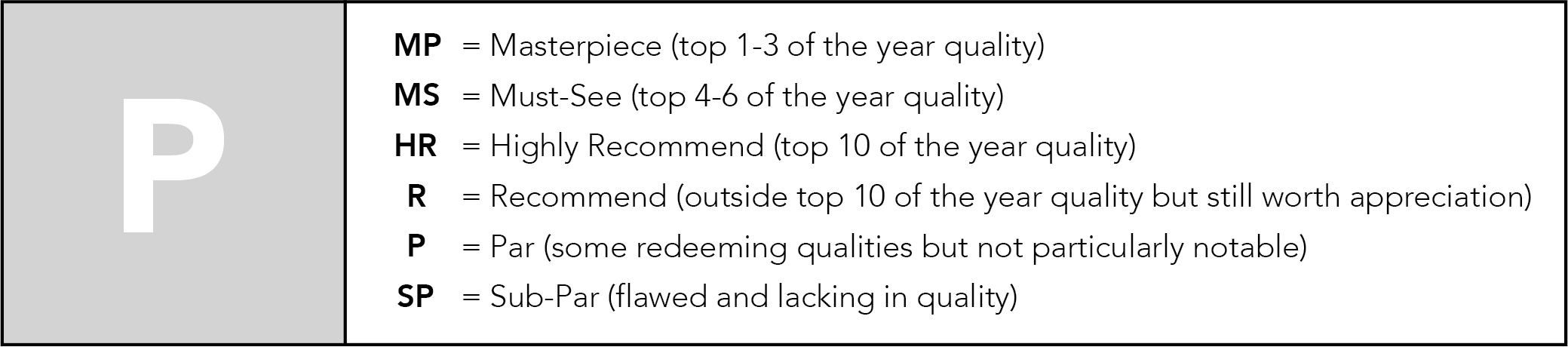

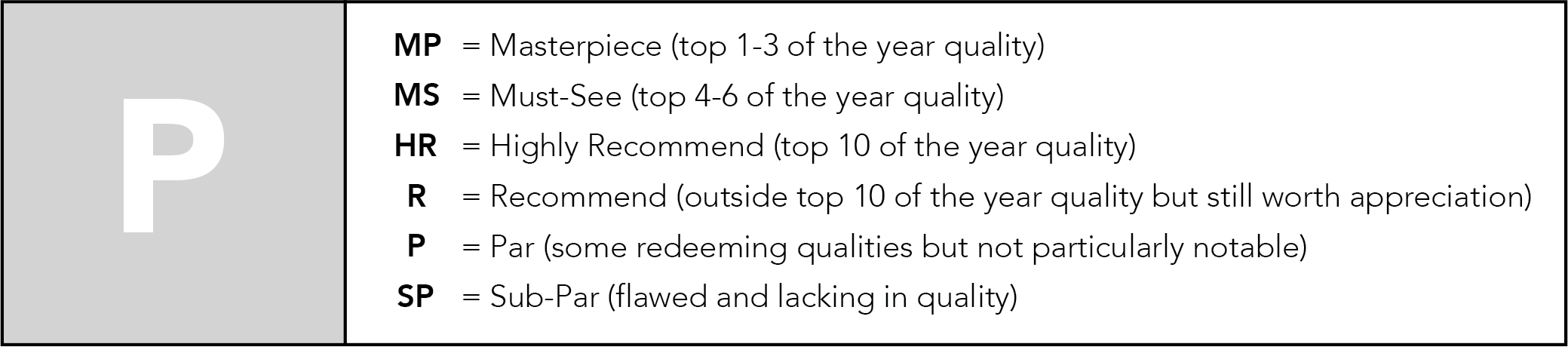

Matt Shakman | 1hr 55min

Leading up to its release, The Fantastic Four: First Steps seemed to have all the right ingredients for a standout instalment in the Marvel Cinematic Universe, poised to defy the iconic superhero team’s history of poor movie adaptations. WandaVision and It’s Always Sunny in Philadelphia have previously benefited from Matt Shakman’s direction, and even the marketing heralded a rare Marvel film with its own unique aesthetic, blending retro-futurism with mid-century modern production design. For the first act too, we’re given exactly what we were promised – a cosy family dynamic à la The Jetsons, set in an eternally optimistic, never-ending Space Age held together by these noble astronauts.

It is once the threat of the planet-devouring Galactus emerges that The Fantastic Four falters, shedding its kitschy 60s fashion and Kubrickian interiors for overblown digital effects rendered with far less imagination. Either Shakman suddenly forgot how to use colour at this point, or he was too distracted by the apocalyptic scale to carry through his commendable style, but either way there’s little which gives these climactic stakes any visual character. For what is effectively one of the most powerful beings in the Marvel multiverse, Galactus is disappointingly dull, only vaguely becoming a figure of interest when he carelessly treads through New York City like some cosmic kaiju. Even when Shakman does return to his inspired production design, it feels wasted, relegated to the background of conversations and denied any thoughtful framing.

This is a film which works best when its central cast is simply allowed to relax in each other’s company, letting Mr. Fantastic and Sue Storm work through their new roles as parents, while Johnny Storm and the Thing fill in as uncles to the newborn Franklin. Besides the insufferably forced running gag around one character’s cheesy catchphrase, their collective chemistry is organic, especially capturing the joys and concerns of raising a child in Pedro Pascal and Vanessa Kirby’s performances. With each core member of the team representing the four classical elements, they are firmly rooted in archetypes that shape and balance their relationships, yet are also given room to evolve beyond them.

Family is about having something bigger than yourself, we are told, though it’s hard not to wish their story engaged more closely with the moral dilemma which forces them to choose between their baby and the world at large. That it takes little agonising to decide which direction to take is fine, though even the social consequences are relatively muted in this utopia which elevates them to an almost unquestionable, godlike status. Their ability to unite every single nation against an alien threat is effortless, and as such, the story never truly tests our heroes beyond the superficial strength of their willpower. Shakman’s vision of the The Fantastic Four may gesture towards greatness, but it ultimately retreats into hollow grandeur, leaving behind a world rich in style and depth for a simulation that never dares to challenge its own ideals.

The Fantastic Four: First Steps is currently playing in theatres.