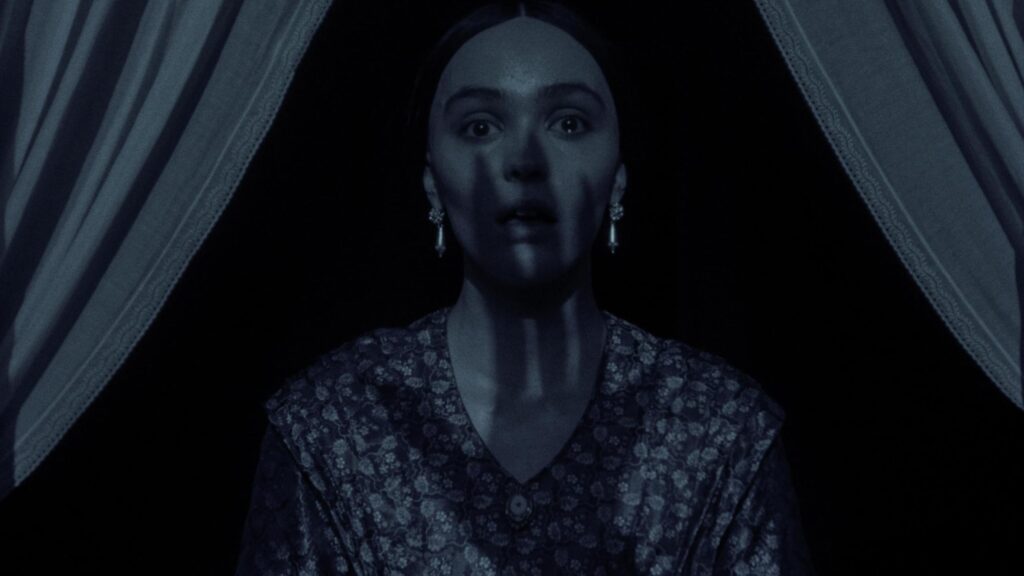

La Bête Humaine (1938)

The affliction which plagues one mild-mannered train driver with bouts of rage might as well be a blood curse in La Bete Humaine, and fate does not look kindly on those who tempt the beast, as Jean Renoir delicately lays out the blueprint of corrupted antiheroes and femme fatales in his tragic fable of man’s inner madness.