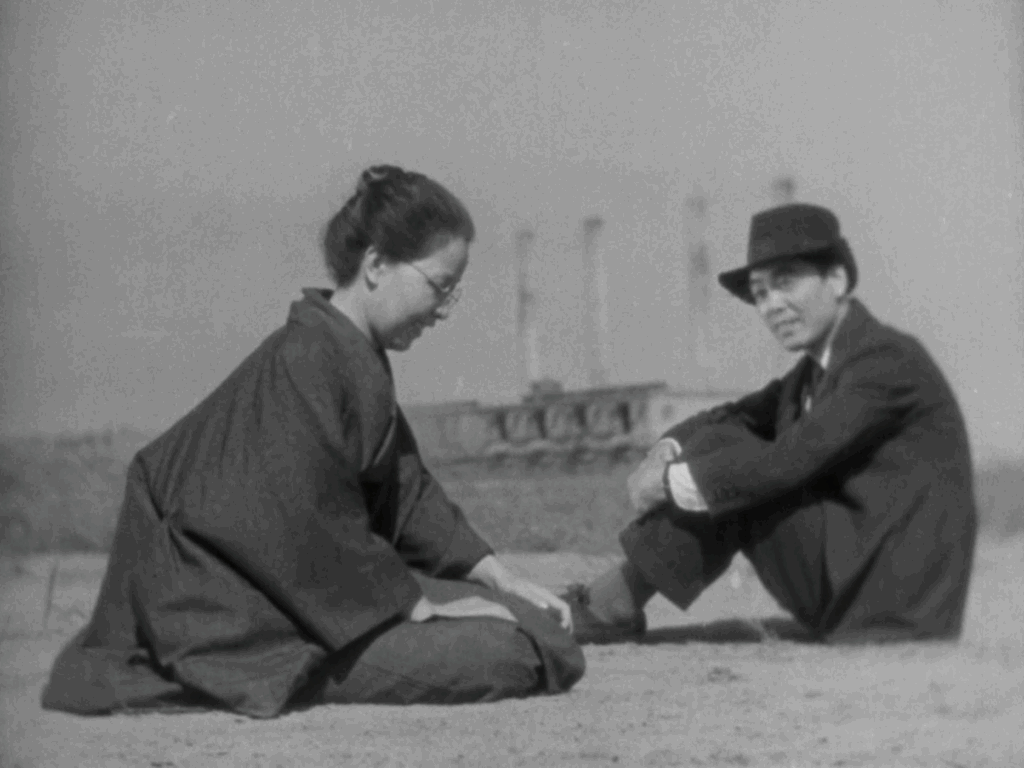

No Other Choice (2025)

Never has Park Chan-wook wielded his fatalistic irony with such a darkly comedic edge as he does in No Other Choice, sending one unemployed paper specialist on a murderous trail against rival job candidates, and sharply exposing the bureaucratic nihilism of modern capitalism.