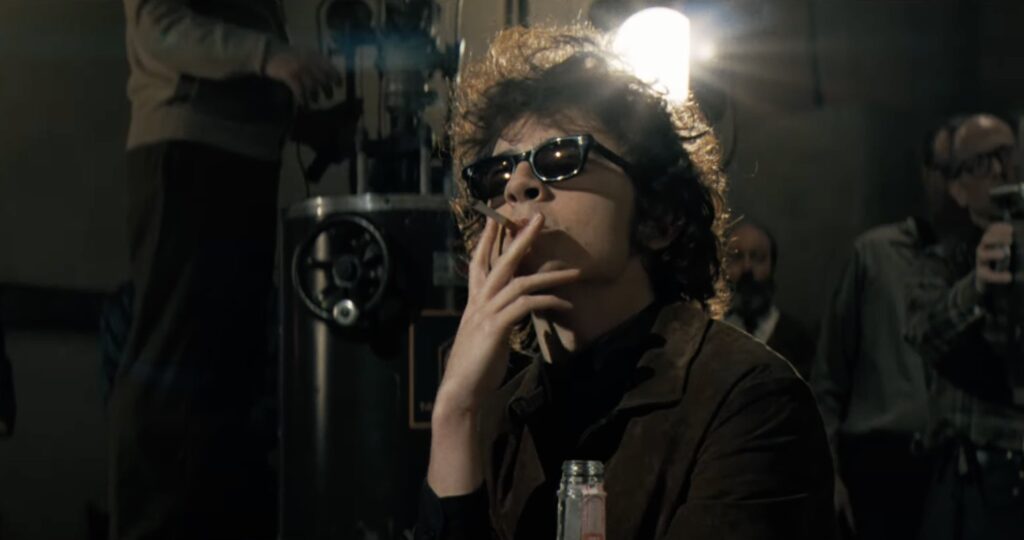

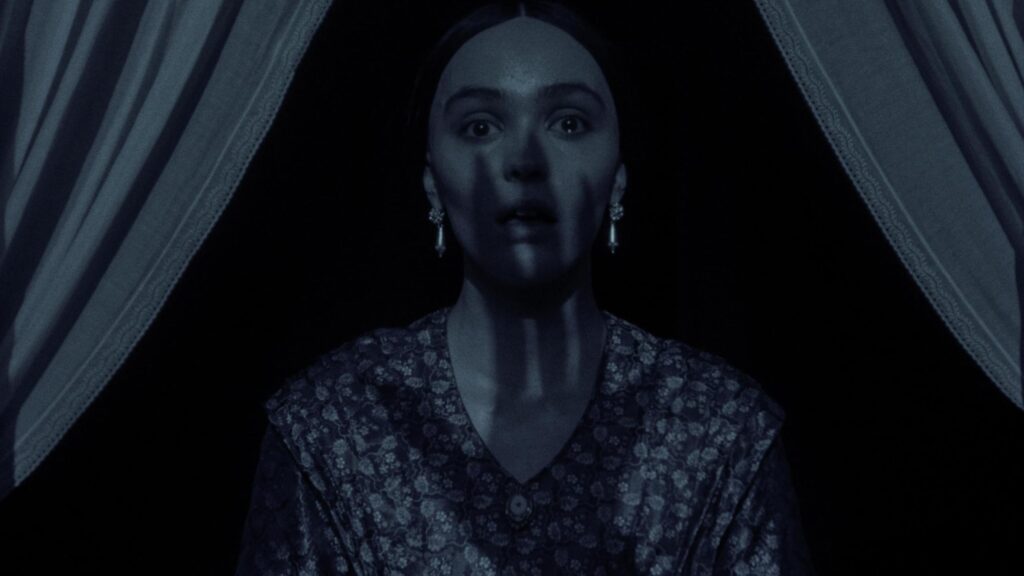

Emilia Pérez (2024)

Jacques Audiard is no hack, and there is some merit to the outlandish ambition of this pulpy, musical melodrama about a cartel kingpin’s transition, yet its constant misfires keep Emilia Pérez from ever settling on a coherent direction.