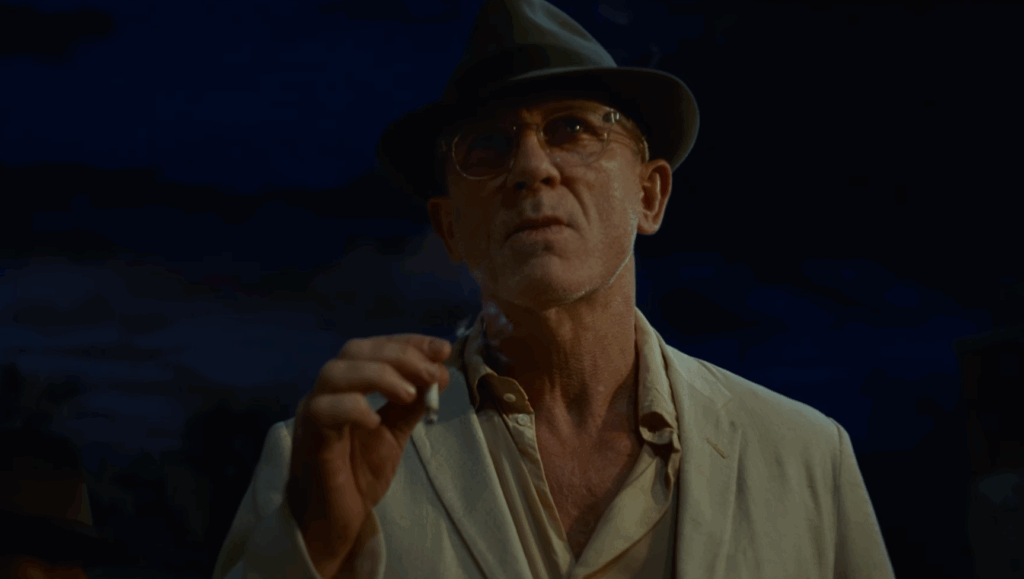

F1 (2025)

Joseph Kosinski swaps jets for race cars in F1’s thrilling sports drama, stylishly redressing familiar tropes with sleek technical mastery, and turning its predictable rivalry into an electrifying, finely choreographed dance of collaboration.