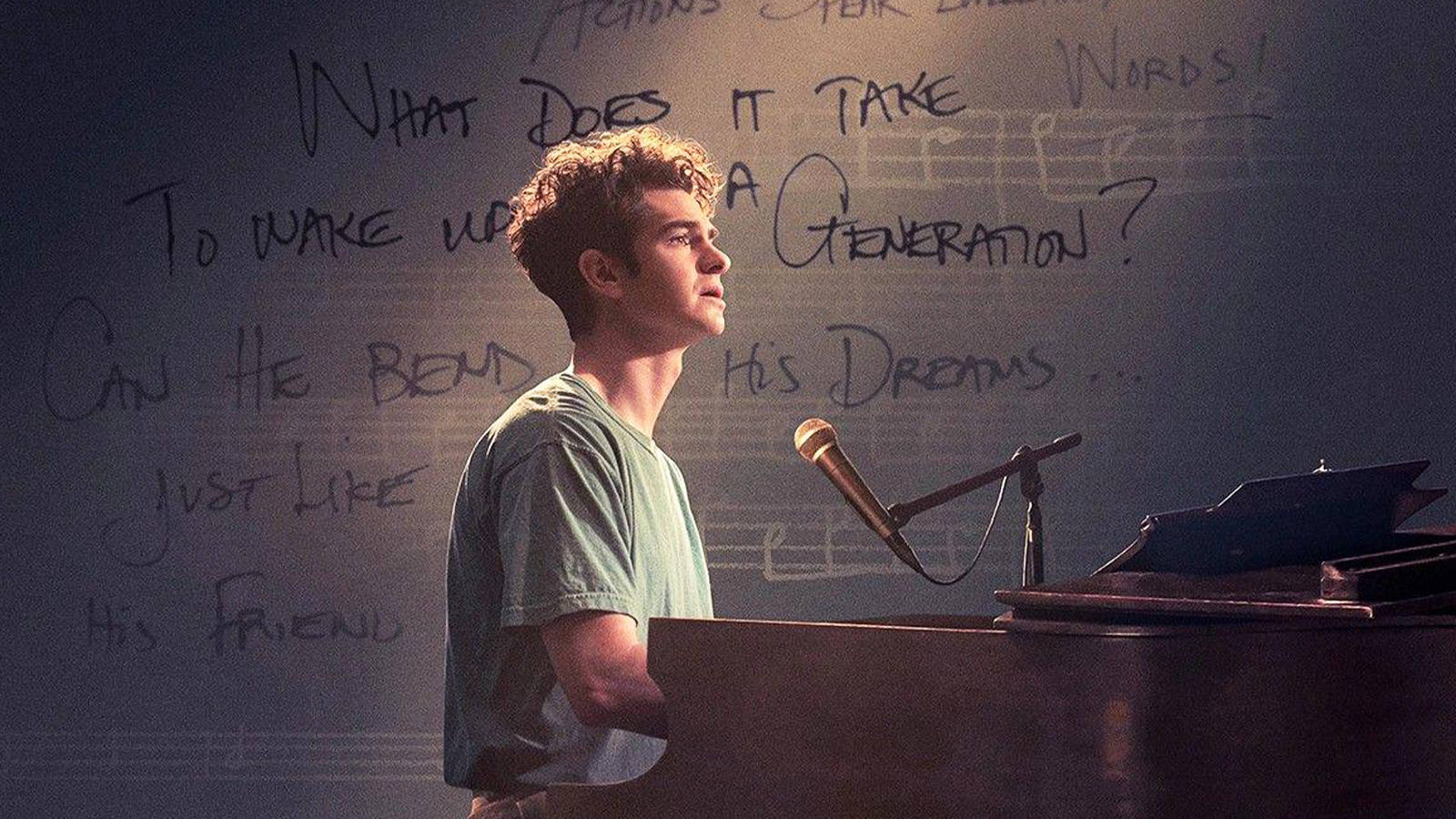

Tick, Tick… Boom! (2021)

Tick, Tick… Boom! seeps with a zest for life shared by both director Lin-Manuel Miranda and his subject of fascination, musical theatre writer Jonathan Larson, openly embracing notions of bohemia and self-aware numbers in a deconstruction of artistic ambitions, obsessions, and egos.