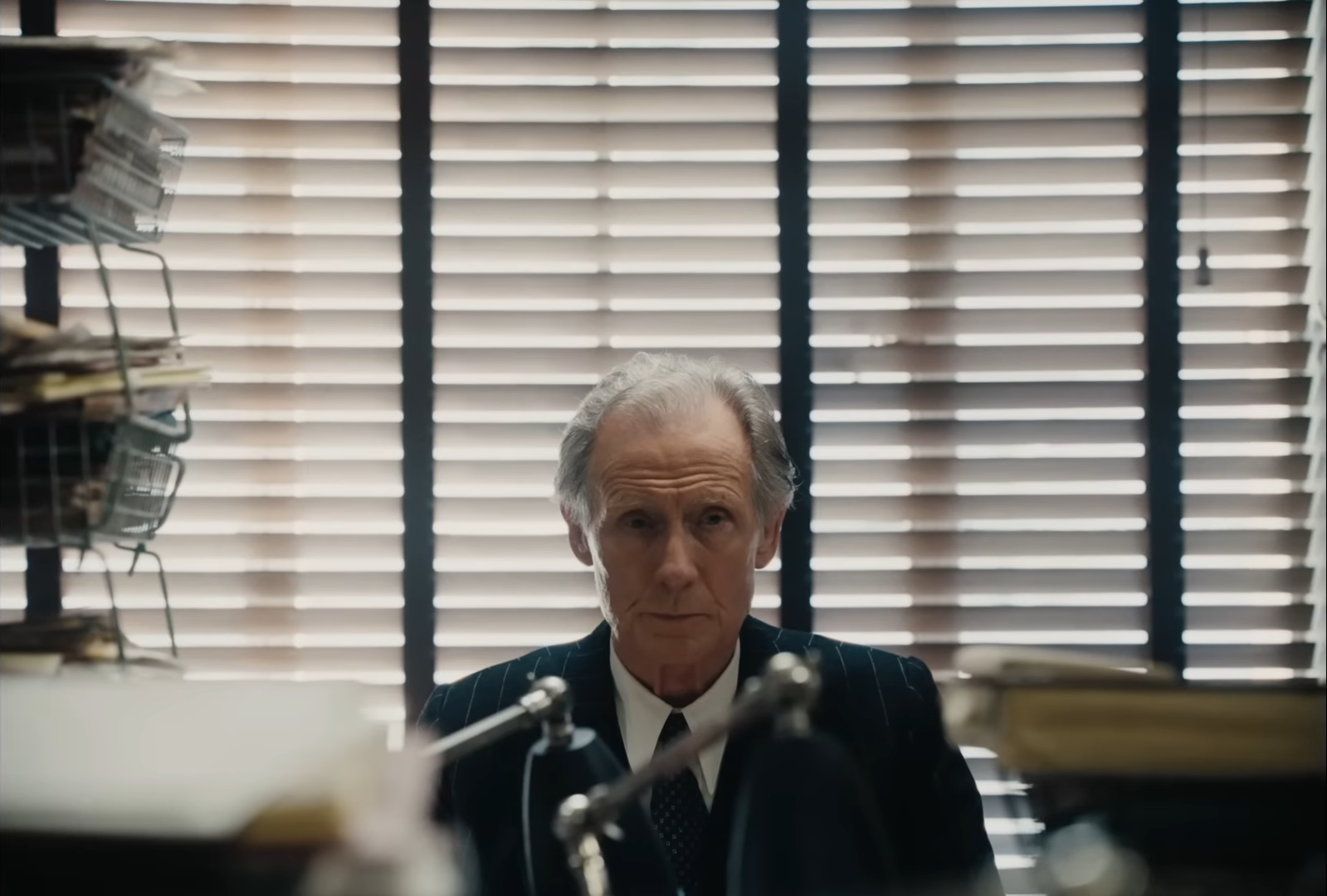

The Pale Blue Eye (2022)

As the chilly mist clears across Scott Cooper’s frozen landscapes in The Pale Blue Eye, an intriguing murder mystery of occult horror and dark family secrets emerges, conceiving what Gothic evils and melancholy regrets might have given birth to the morbid imagination of Edgar Allen Poe.