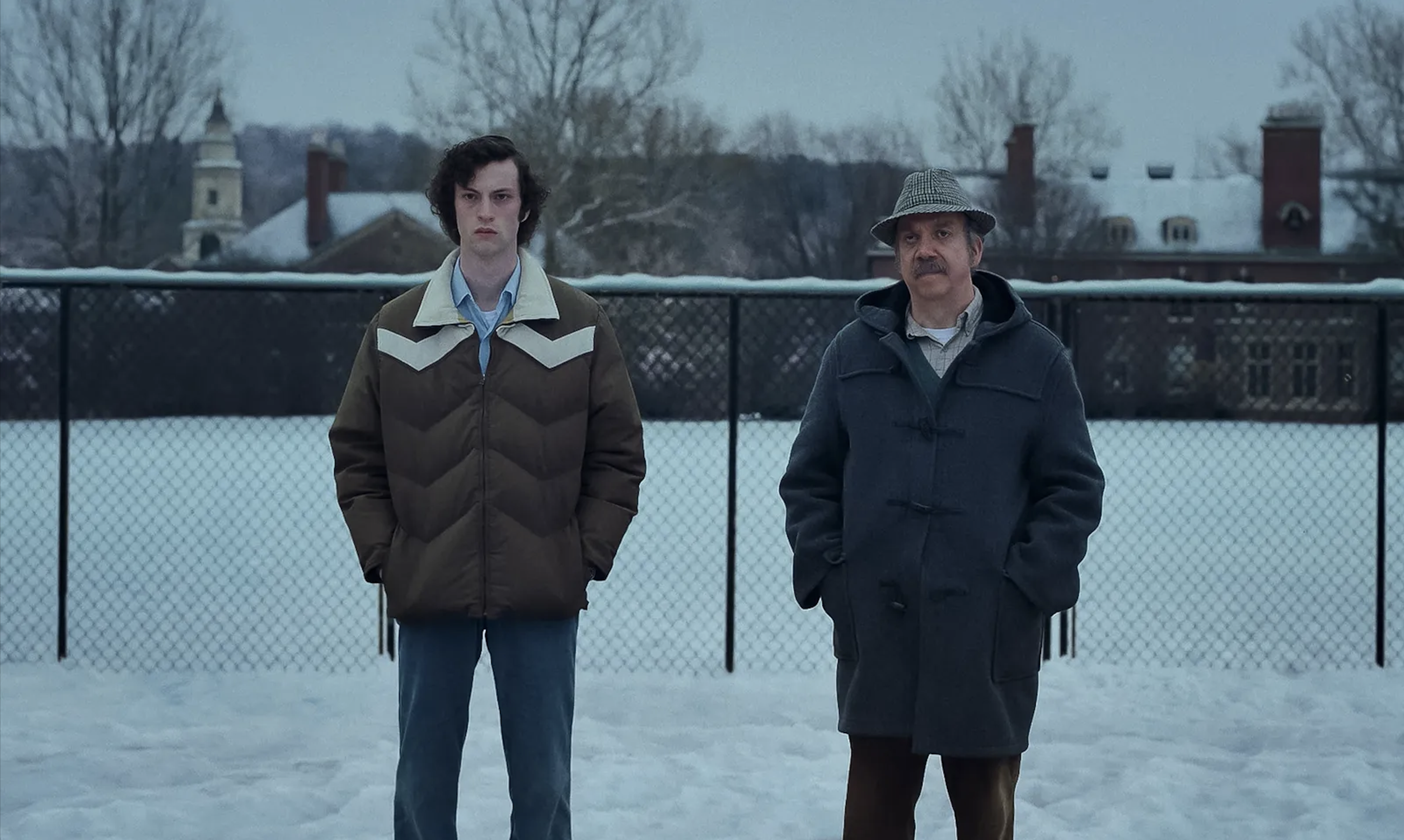

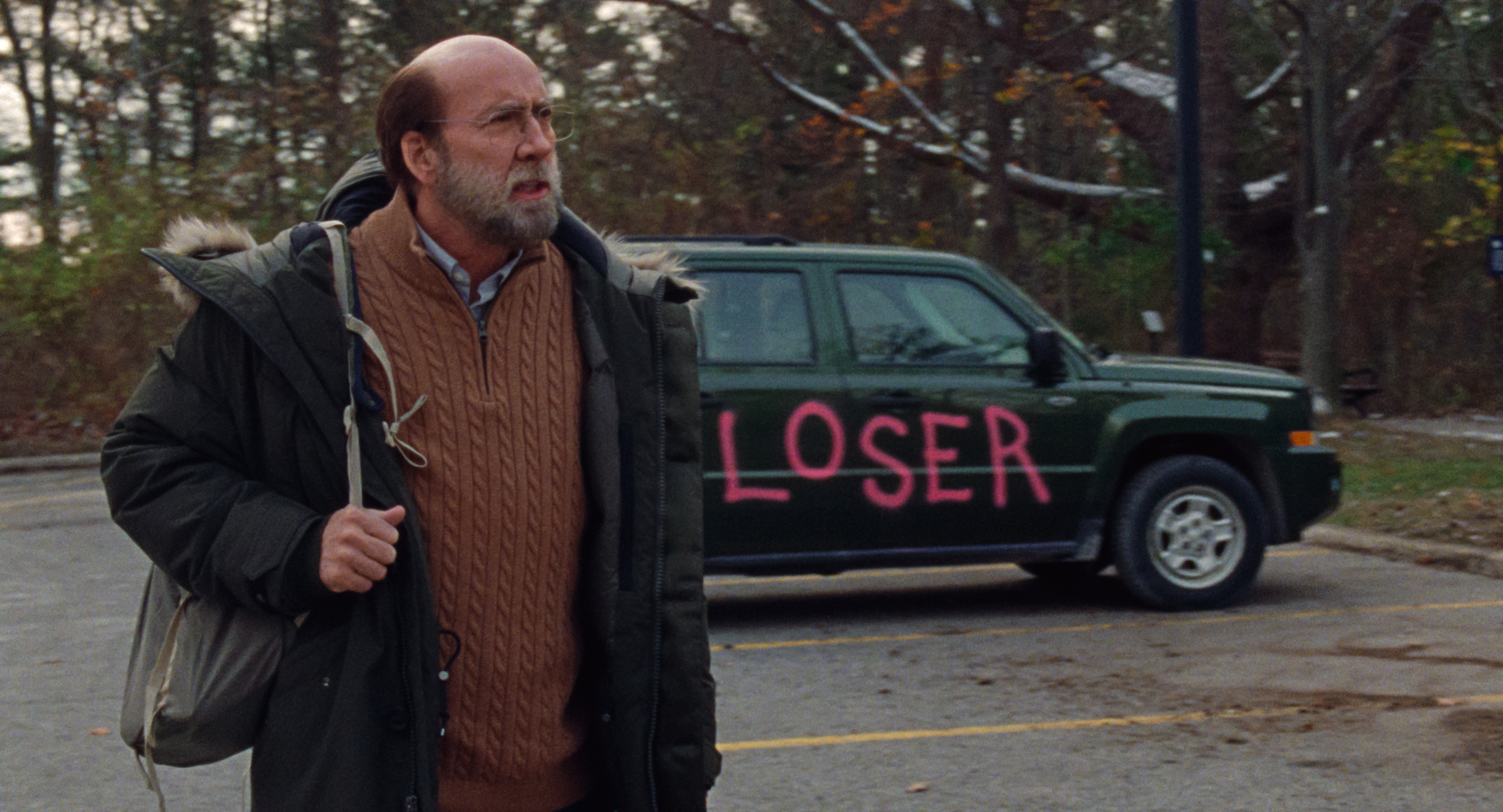

Maestro (2023)

To work as both a conductor and composer is to live two separate lives, Leonard Bernstein ruminates in Maestro, and it is this duality which Bradley Cooper reverberates all through his biopic of the great musician, revealing with sweeping passion and subdued restraint the contradictions that lie at the heart of genius.