Cristian Mungiu | 1hr 53min

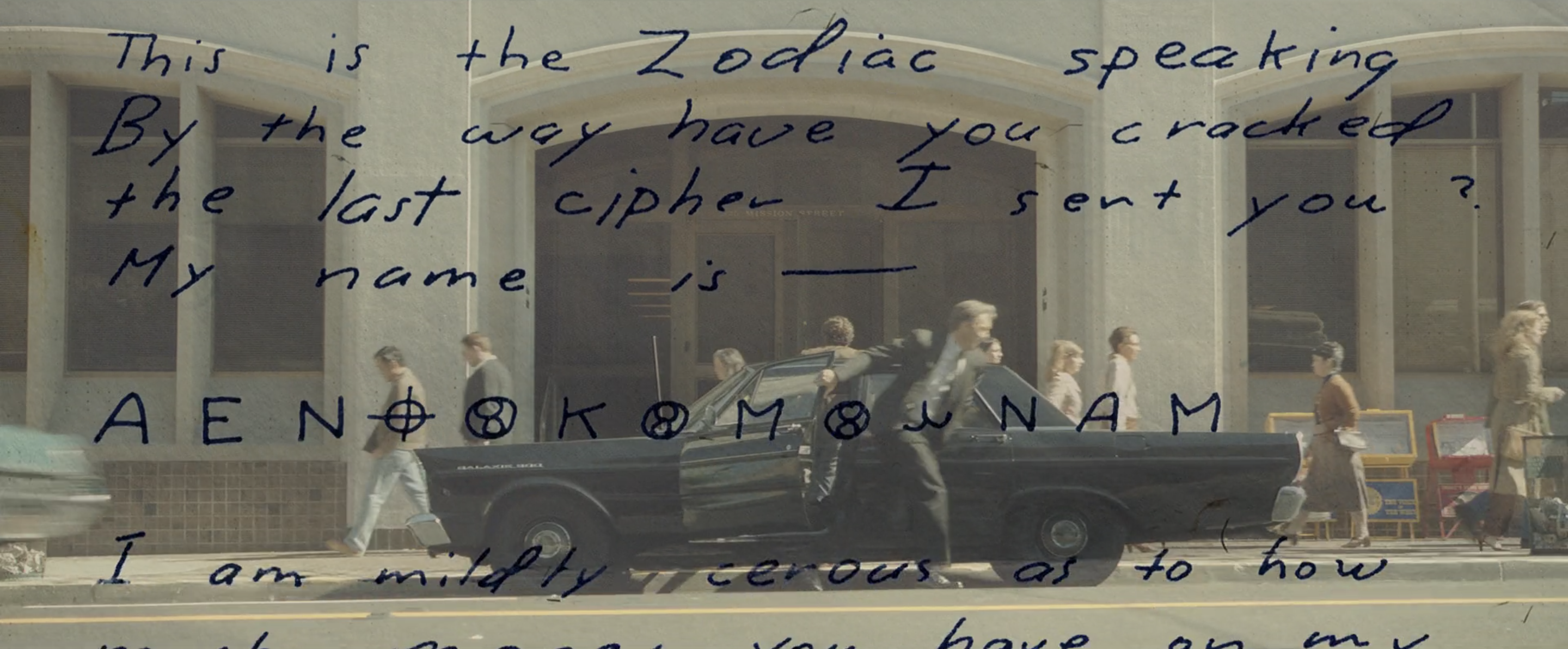

The word ‘abortion’ is not spoken until thirty-five minutes into 4 Months, 3 Weeks and 2 Days, but even with all the awkward side-stepping around the point, Cristian Mungiu still forms a clear, excruciating picture of the harrowing ordeal at hand. In fact, it is more often through those details purposefully kept out of view that this story progresses, and the formal justification of this withholding, minimalist style is powerful. Living in 1987 Communist Romania, university students Otilia and Găbița would be threatened with lengthy prison sentences if their plans to terminate an unwanted pregnancy were to get out, and so it is precisely in their covert conduct that we can surmise their unspoken motives and profound discomfort. Leading the peak of the Romanian New Wave, Mungiu turns his government’s historic oppression into a pervasive, unseen antagonist, haunting the claustrophobic silences of this naturalistic thriller with cold, passive cruelty.

Though it is Găbița who is pregnant, Mungiu wisely sticks us in the perspective of her friend, Otilia, tasking her with finding an illegal abortionist, booking a hotel room for the procedure, and eventually disposing of the foetus. Anamaria Marinca consequently does most of the speaking in this cast, and yet it is her silent, expressive acting which is her most impressive ability, kept at a distance in medium and wide shots. Duration is one of Mungiu’s greatest tools here, both in the confined time span of 24 hours that instil the film with pressing urgency, and in uncomfortably long takes which let us feel those minutes tangibly slip by. Slotted in between the abortion-centric scenes, Otilia finds the low-stakes mundanity of everyday life creeping in, and as she sits at a crowded table where her boyfriend’s mother is celebrating her birthday, Mungiu hangs on her face for close to eight minutes. Tedious conversation, hands, and dishes move all around her, she is briefly chided by a guest for smoking, and in her anxious, detached expression we can see that this is the last place she wants to be after everything that has just gone down.

Otilia often finds herself centred in Mungiu’s compositions all throughout the film, as earlier in the hotel room where the surly abortionist, Mr Bebe, informs, warns, and patronises the two women, she is staged between him and Găbița like the mediator in this transaction. Of course, her role goes far beyond that though. She is also a confidant, an advisor, and an agent acting on her friend’s behalf when she is too nervous. There is no word to explain the role Otilia is forced to play though when it comes to light that they do not have the money for the whole procedure, as Mr Bebe darkly reveals the price that must be paid to go through with it.

“I’ll go in the bathroom. When I come out, you give me your answer. If it’s yes, tell me who goes first. If it’s no, I get up and go.”

Sex is currency in this seedy underworld, and for this particular transaction to go ahead, both women must contribute. Mungiu’s camera stays in the bathroom throughout this sequence, first with Găbița as she turns on the tap to block out the noise and fearfully waits for her turn, and then with Otilia as she enters and immediately starts scrubbing herself clean.

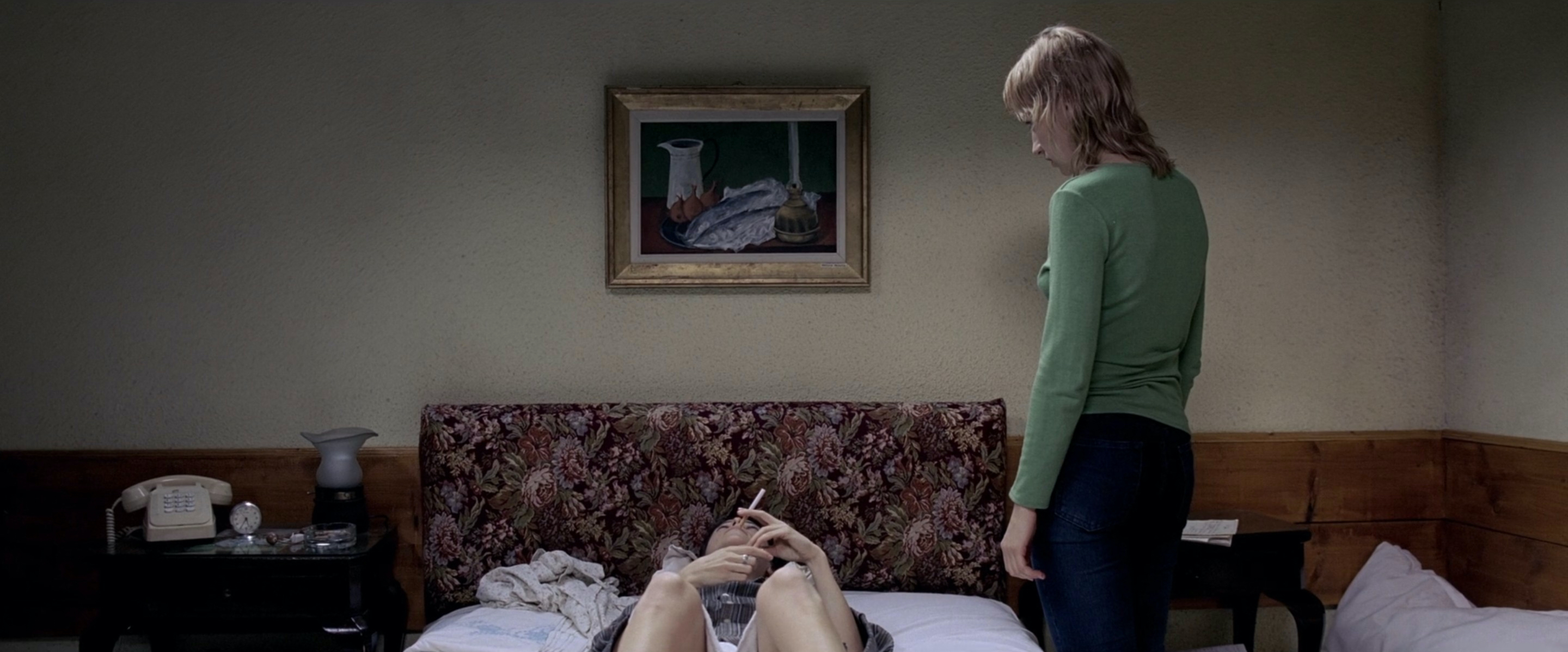

Even in these drably realistic settings, there is a precision to Mungiu’s staging, as immediately following the abortion he sits his camera at the head of the bed where Mr Bebe and Otilia continue to dominate the image, while all that is visible of Găbița are her legs poking into the frame. When we get the reverse shot as well, she is still shoved right down to its bottom-centre, leading our eyes first to Otilia as the largest presence, and secondly to the dreary still life painting hanging above the bed – a meagre flourish of beauty in this bleak hotel room. As if forcing Găbița to the edges of her own story, Otilia’s guilty resentment spills outwards into these visuals, angrily directed at her friend’s lack of independence that has partially offloaded her trauma onto others. After all they have gone through, perhaps it is this tragic wedge driven between them which will affect their relationship most deeply.

It is a rigorous, unforgiving aesthetic which Mungiu commits to, comparable to Michael Haneke’s films in the chilling severity of its long, distant takes, though far more embracing of handheld camerawork to build an almost Hitchcockian suspense through tracking shots. As we walk with Otilia through the streets, we both get a fright as children playing nearby kick a ball against a car. When it’s time to bring this slow-burn tension to an end and pull back the curtains on the horror, he doesn’t hold back there either, lingering on the image of the expelled foetus and sucking all remaining mystery out of the daunting procedure.

At times like these, we desperately hang onto the few answers Mungiu gives us, trying to use those to fill the void of questions he has purposefully avoided addressing. Who is the father of Găbița’s unborn baby? What were the circumstances of the pregnancy, and the decision to abort? Who exactly is Romana, the woman who recommended Mr Bebe? With as bare bones an attitude to storytelling as Mungiu displays here, such details are extraneous and don’t figure into the kind of unconditional empathy he evokes for these two women. It is rather in the smothering silences, distant camerawork, and careful staging that we feel the Communist state’s stranglehold over its citizens’ intimate lives, and where this cinematic cornerstone of social realism holds us in its own tight, uncompromising grip.

4 Months, 3 Weeks and 2 Days is not currently available to stream in Australia.