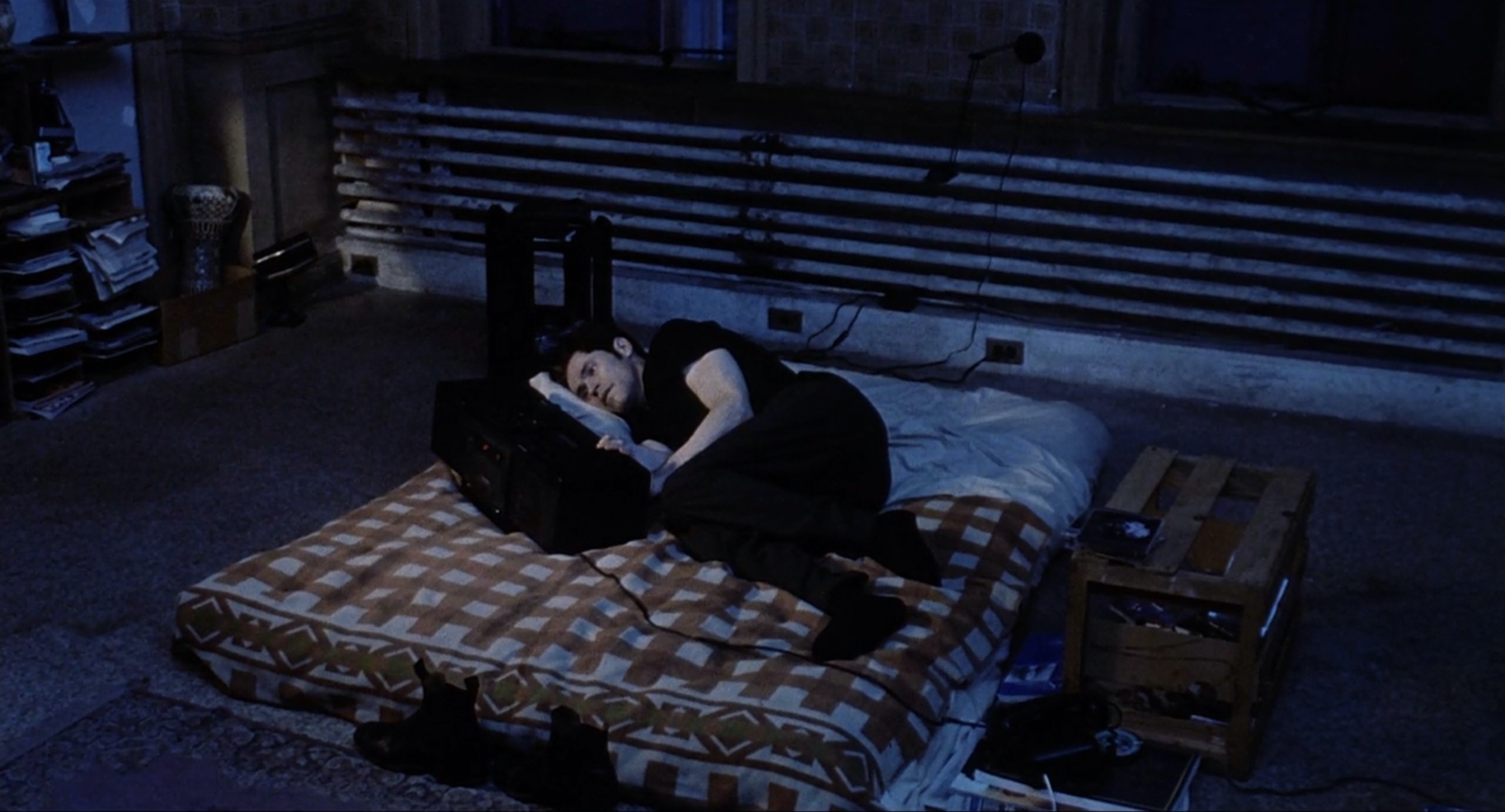

The Last of the Mohicans (1992)

Michael Mann’s grand mythologising of colonial America forecasts a solemn future in The Last of the Mohicans, and yet it is also through the cross-cultural relationships formed between Europeans and Native Americans that seeds of harmony are planted, miraculously blooming in the unfertile soil of war.