Wings of Desire (1987)

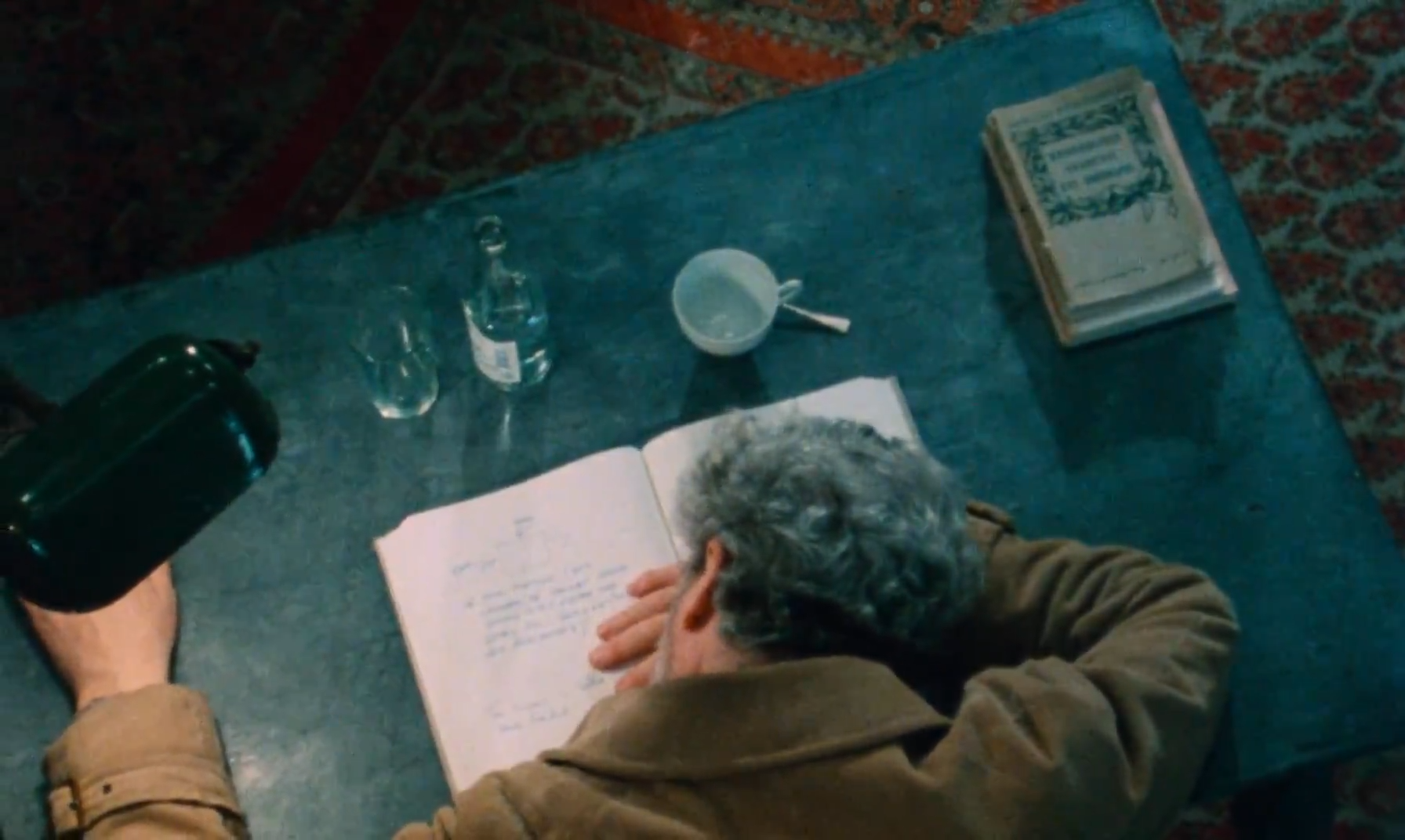

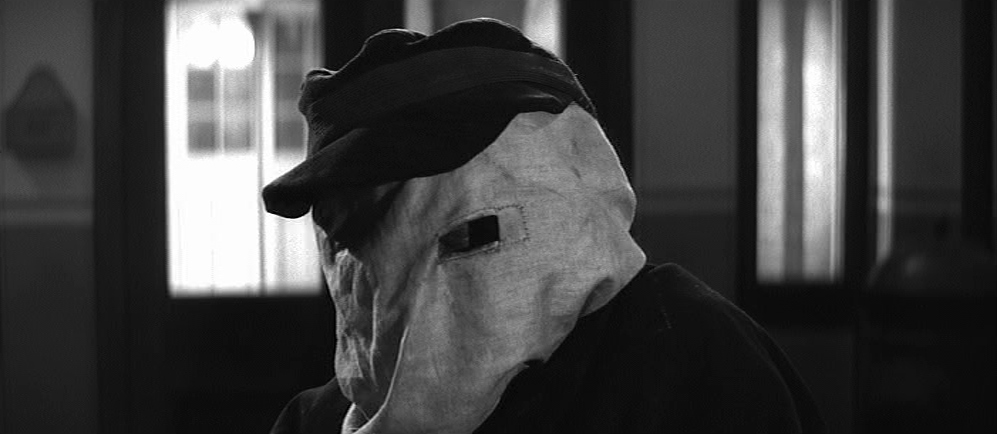

The god’s-eye view of humanity that Wim Wenders grants us in Wings of Desire flies high above 1980s West Berlin with watchful angels, and swoops down low to tune into the intimate thoughts of its citizens, crafting a dreamy city symphony that finds childlike wonder in its everyday pleasures and private sufferings.