Sydney Pollack | 2hr 41min

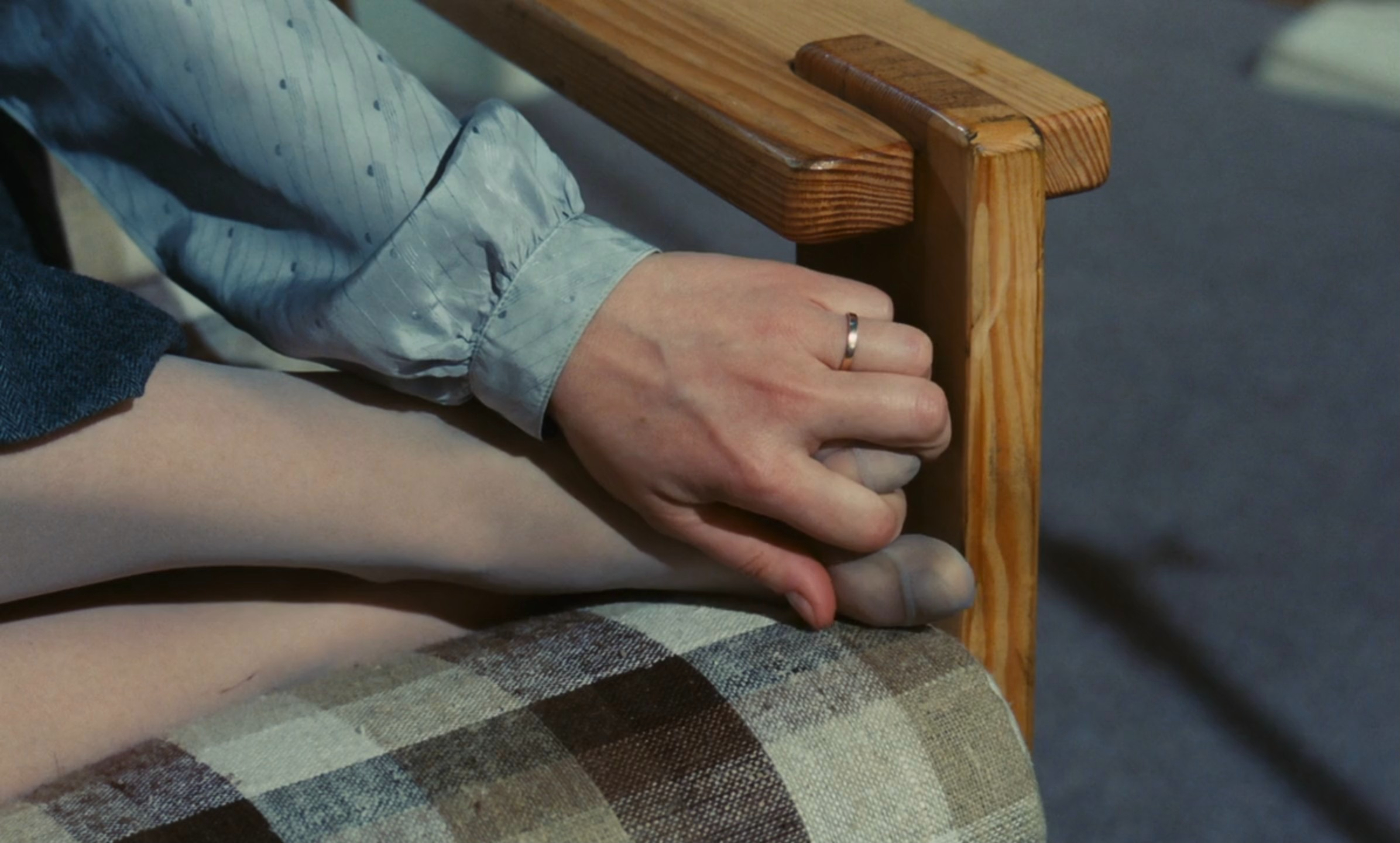

For Baroness Karen von Blixen, the vast plains and farming communities of Africa are a liberating escape. The Danish aristocracy she was born into is one of cold conservatism and rigid social conventions, necessitating a marriage to Baron Bror Blixen – not her first choice, given that he is the brother of the man who spurned her romantic approach, but a satisfactory match nonetheless. The ranch he has purchased in East Africa is to be their new residence, and in time will expose the suffocating confines of her previous home in Europe, as a rejuvenating enlightenment unfolds through meditative voiceovers destined to one day be recorded in the pages of her memoir Out of Africa.

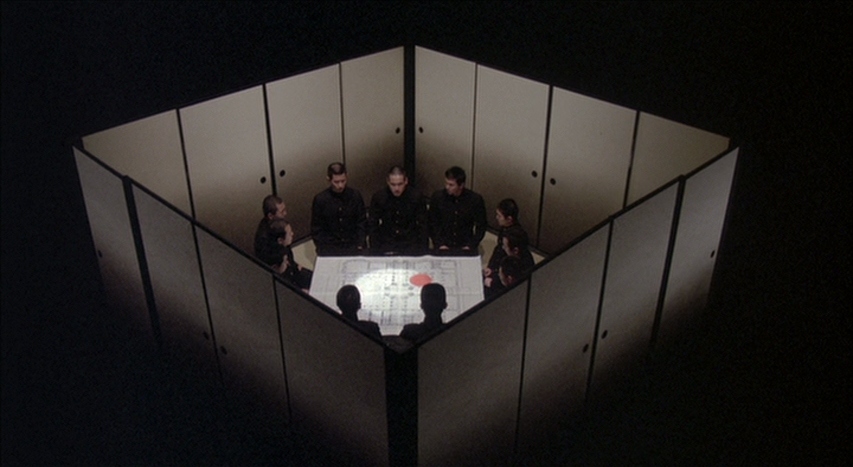

For big-game hunter Denys Finch Hatton however, Africa is not merely an escape when the pressures of the world grow too intense. From the moment he arrived as a young man, there was nowhere else he could have possibly lived. These grasslands and savannahs are his home, not so much soothing his restless soul than embodying the untamed zest for life that has existed inside him since birth. It is clear to see how the romance between Karen and Denys blossoms in their mutual appreciation for this environment and its surrounding culture, yet this subtle difference is not an easy one to overcome. Just as this land of primal beauty defies the influence of its colonisers, so too does Denys resist the expectations of domesticity imposed by European tradition, and its attempts to impose arbitrary structures on life’s natural order.

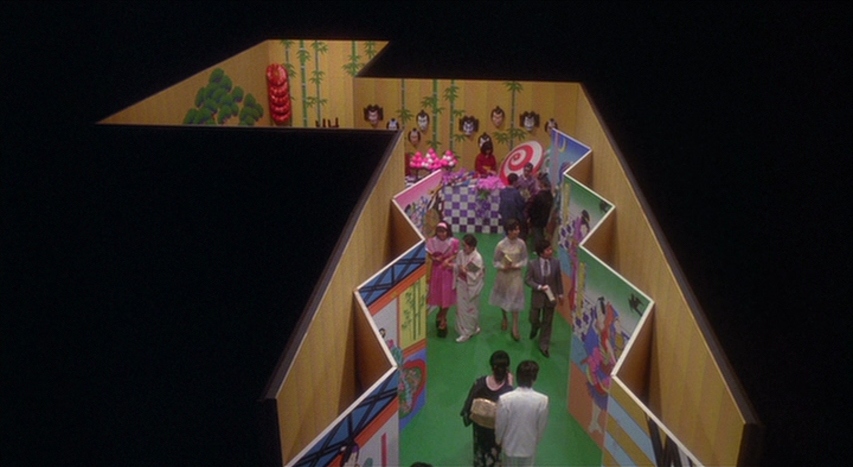

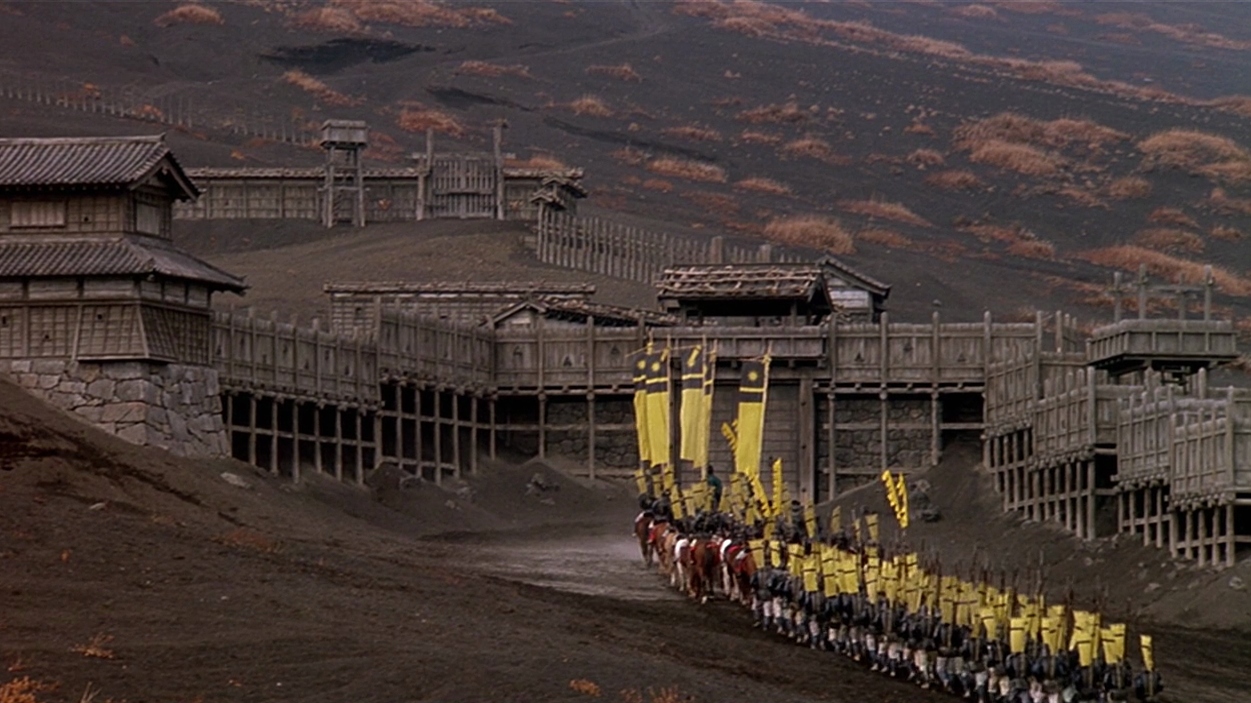

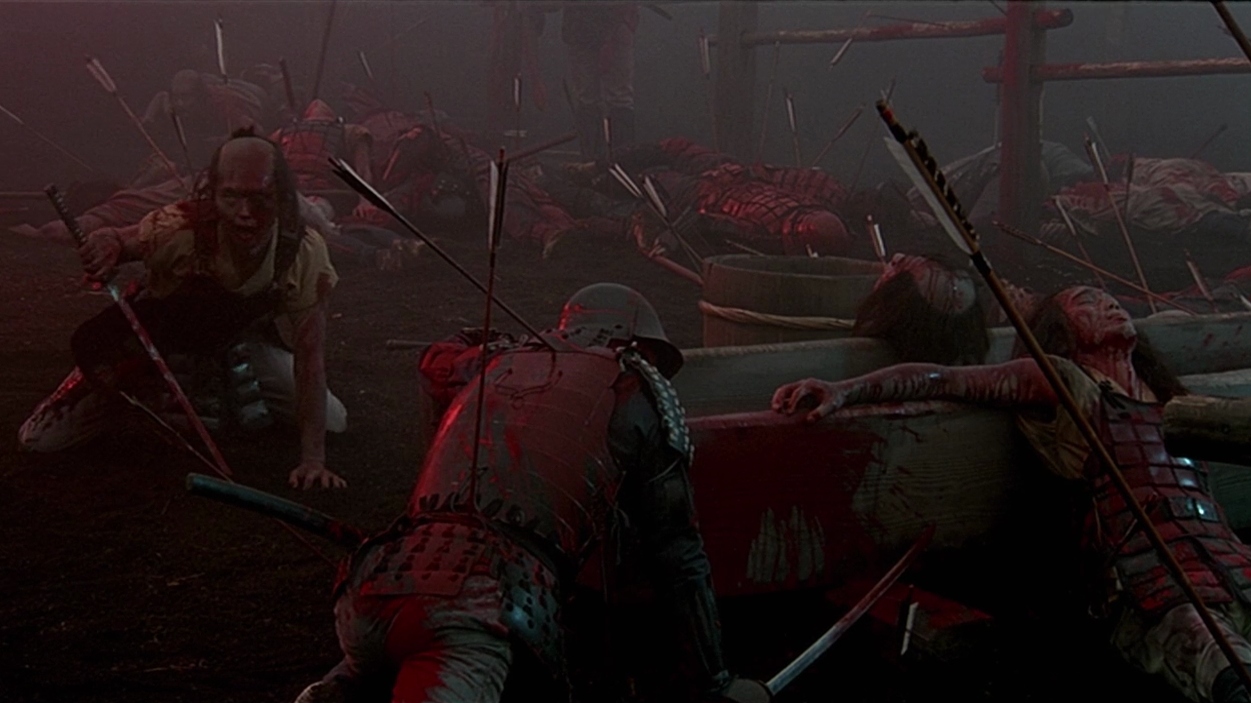

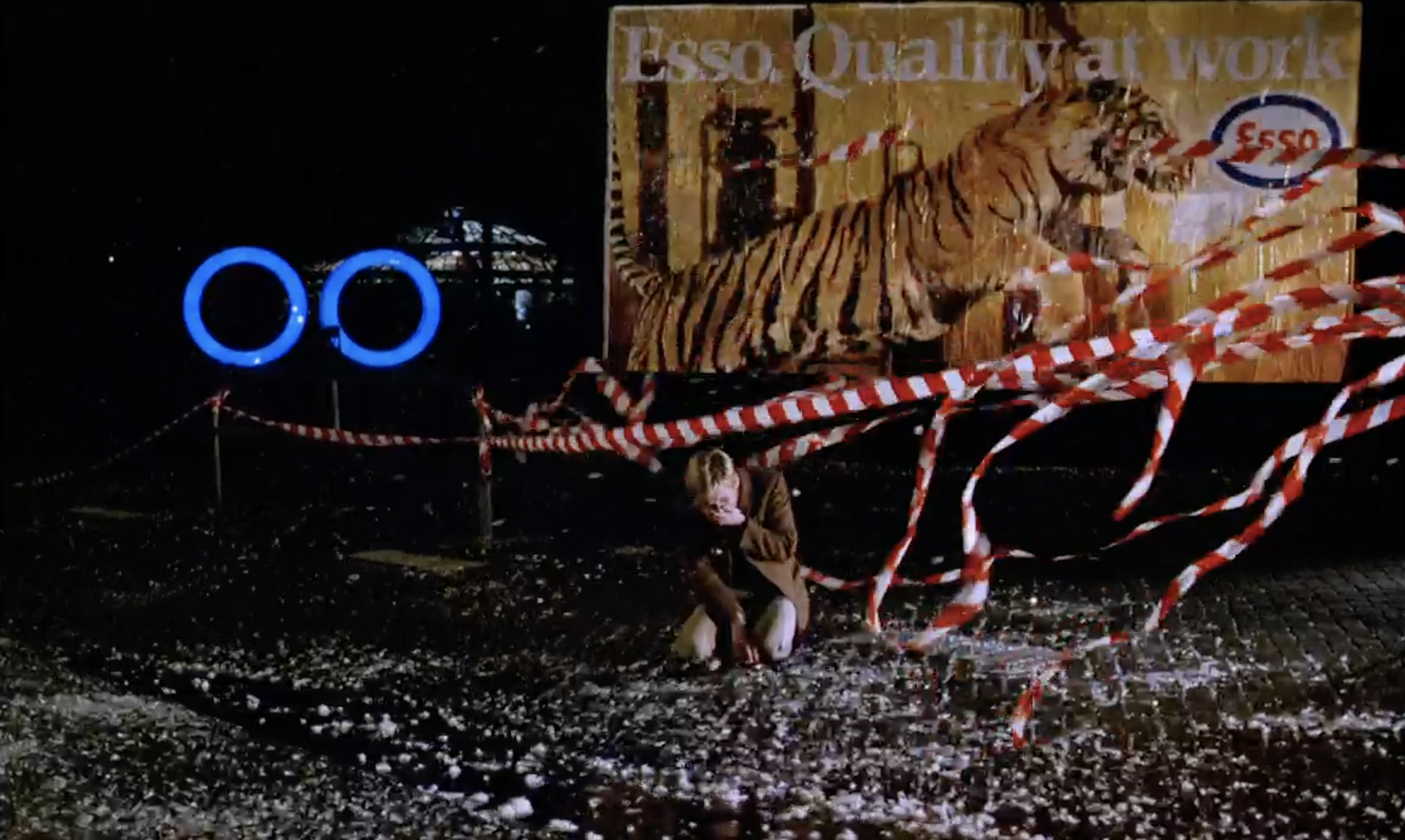

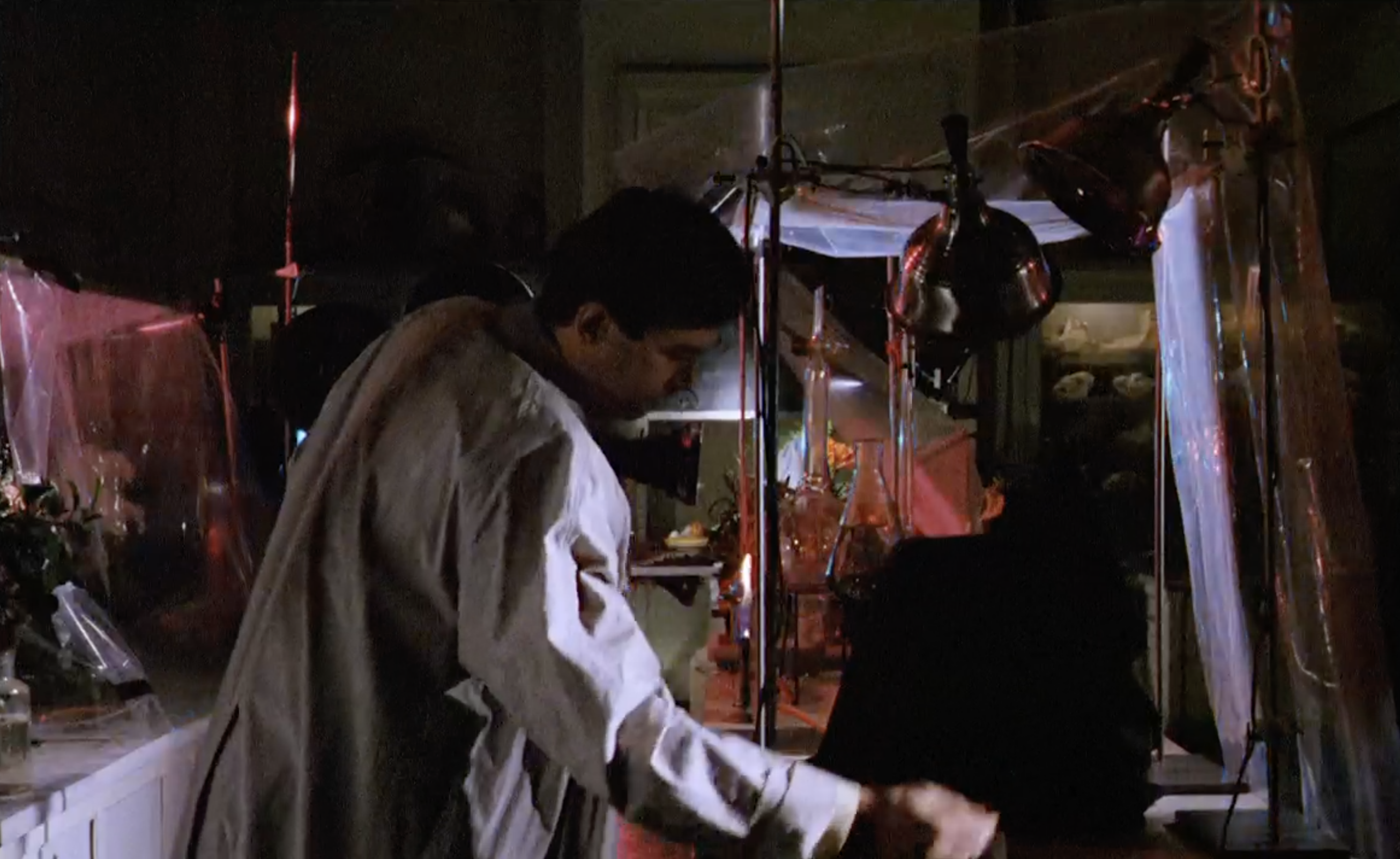

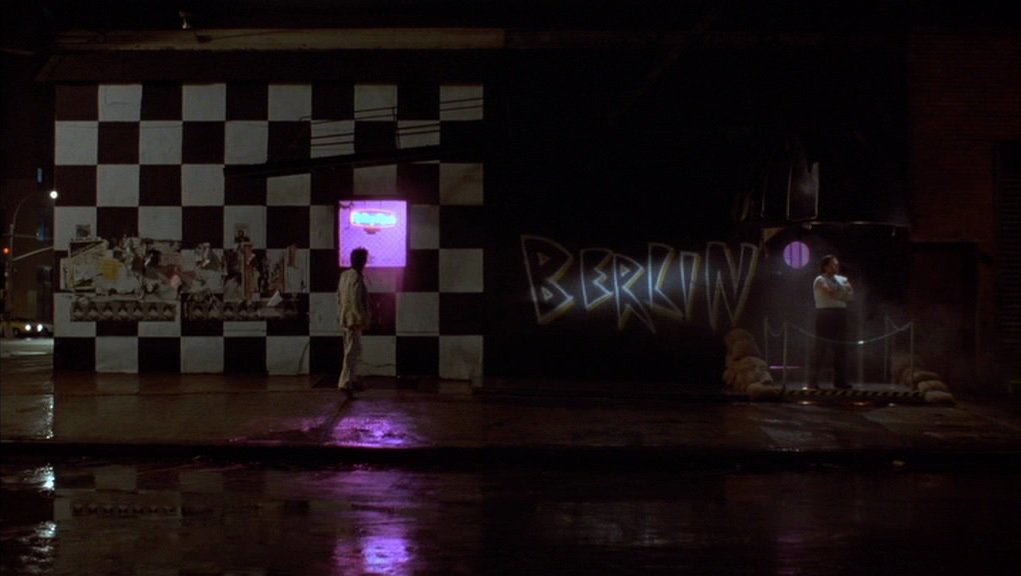

Set against the 1910s colonial backdrop of the nation soon to be officially recognised as Kenya, there are no two ways around Karen’s romanticisation of a disruptive, traumatic era in the history of the region, yet there is little else one can expect from the sentimental reminiscences of a Danish noblewoman. Though she labours alongside Kikuyu workers on her coffee plantation, she lives in a bubble of idyllic bliss distant from their hardships, gracefully delineated through the entwining of her lyrical narration with Sydney Pollack’s impressionistic editing. Long dissolves weave a dreamy elegance through scene transitions, and gentle montages formally bridge gaps in time between each episode in her life as she poetically reflects on her deep connection to the land, persisting even during her brief return home to Denmark. Naturally, this development unfolds purely through voiceover, as the visuals effectively keep us present with her distracted heart and mind in Africa.

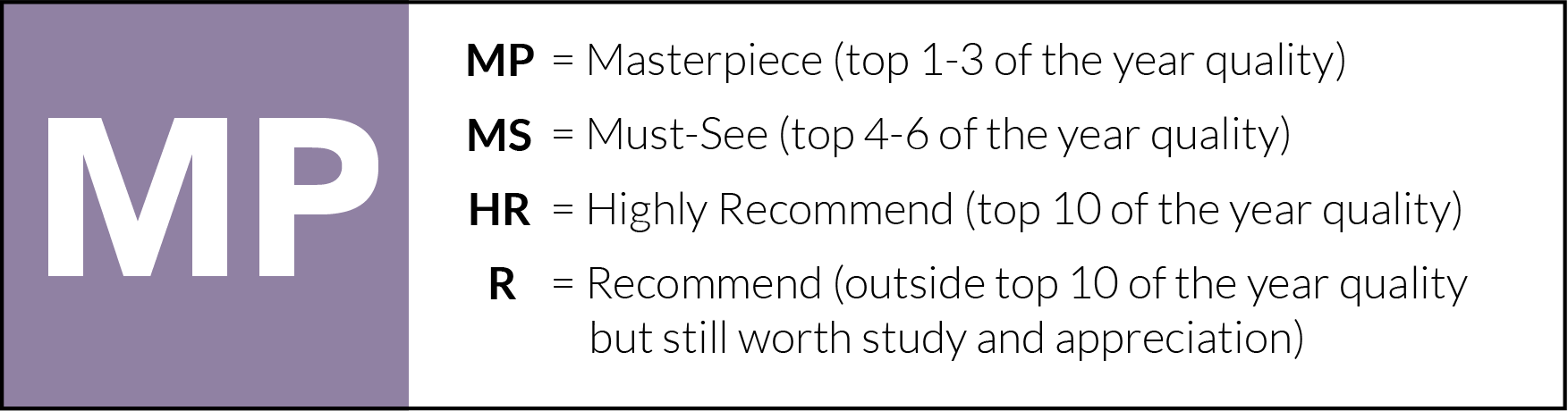

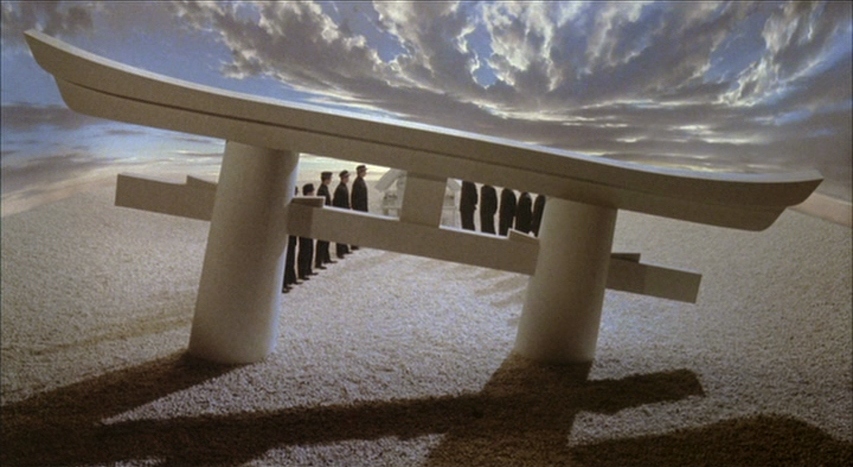

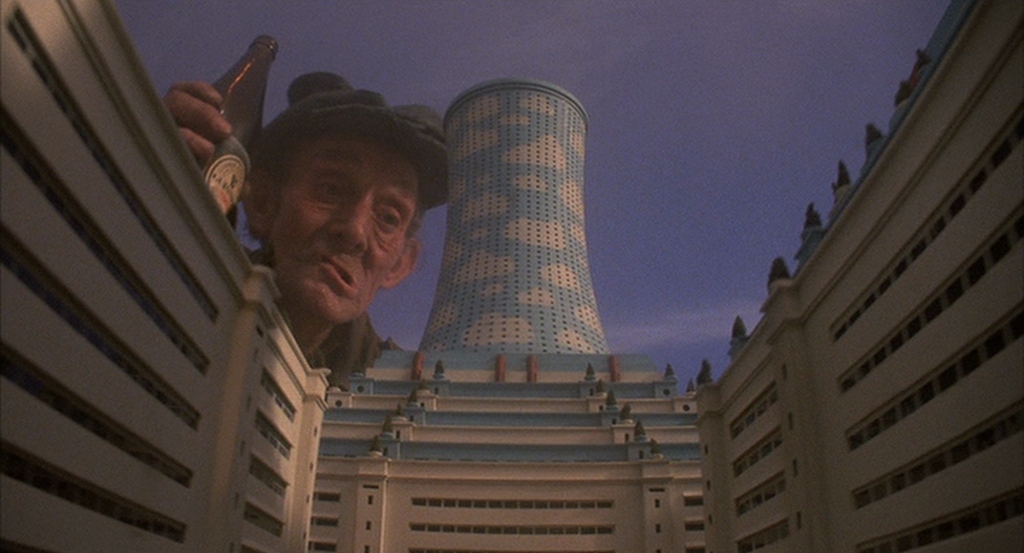

The impact of these montages are only magnified by Pollack’s vibrant photography of Kenya’s expansive vistas, imprinting silhouettes of men and animals against hazy, red sunsets, and composing establishing shots from its dry desert scenery with a picturesque grandeur. The period production design of 1910s colonial Africa is certainly a fine accomplishment too, capturing Europe’s attempt to maintain a semblance of noble sophistication as they impose their highbrow culture on such rugged landscapes, though Out of Africa rises to even greater stylistic heights when Denys finally invites Karen aboard his biplane. Even the film’s greatest detractors cannot deny the raw power of this sequence, gliding through aerial shots of flamingos flocking across lakes, wildebeest herds galloping through plains, and waterfalls cascading into lush green forests. John Barry’s grand orchestral score reaches its dynamic peak here too, evocatively recapitulating the film’s main theme which, like the plane itself, continues ascending until it reaches a scintillating climax.

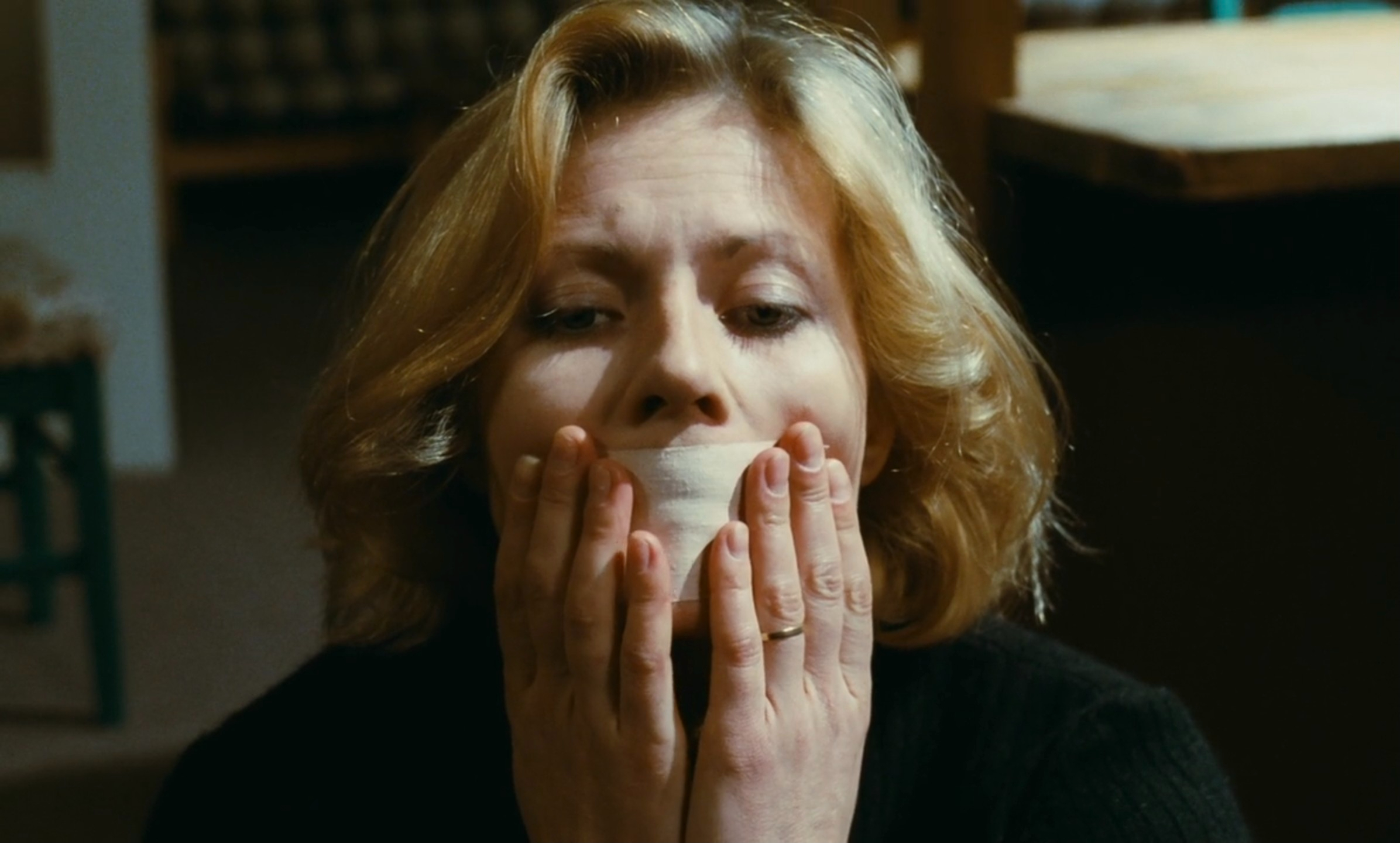

The irony that underlies this scene’s long shots sets in with a mournful realisation – our appreciation of Africa’s staggering beauty only increases the further up we fly, with the scenery eventually disappearing altogether once we are above the clouds. These stunning landscapes can be remotely admired, but never fully embraced by an outsider like Karen, and through this conceit Out of Africa develops an eloquent metaphor for her own relationship with Denys. The nostalgic subtext of her narration tenderly illustrates this yearning, reflecting on just how much her love for both the man and his habitat has magnified from a distance, while Meryl Streep’s astounding emulation of the real Karen von Blixen’s Danish accent imbues her contemplations with an almost musical quality.

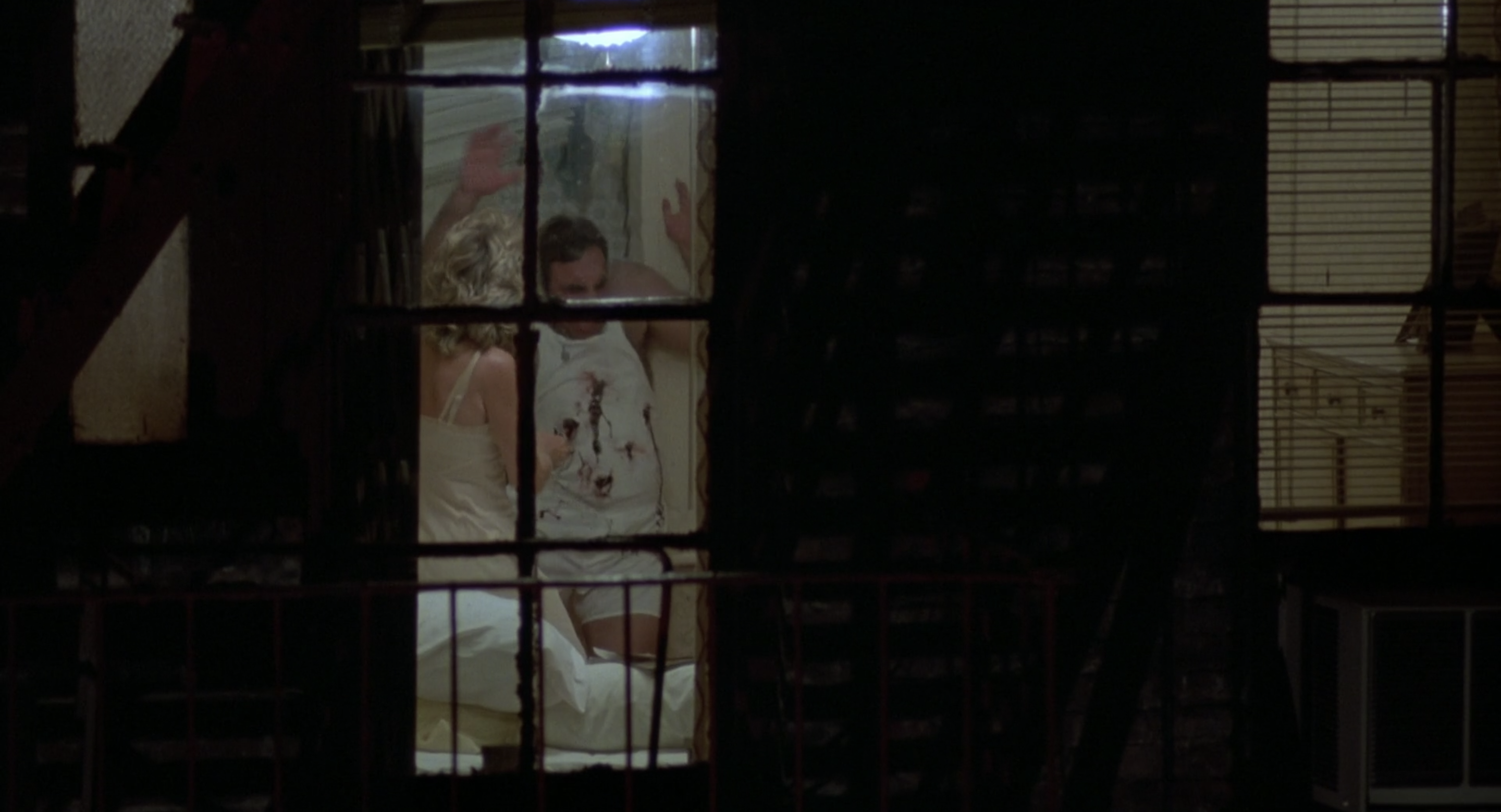

If there is any regret expressed in these voiceovers, then it comes with full understanding that there was never any possible long-term relationship between Karen nor Denys that would have satisfied both parties. She requires stability following her divorce from Bror, yet Denys makes it abundantly clear that he does not wish to be tied down to any oppressive institution that might potentially tear him away from the wild whims of his heart. As such, their passionate romance begins to fade into memory, and is soon definitively buried with Denys’ body after a tragic biplane accident. “He brought us joy, and we loved him well,” Karen dolefully eulogises at his funeral. As she gazes out over the spectacular view from his grave though, she knows she cannot lay claim to his heart.

“He was not ours. He was not mine.”

If Africa and Denys are one in Karen’s mind, then the fire which destroys her farm and sends her back home to Denmark is essentially analogous with her lover’s death. As she quietly wanders among its people and terrains for the last time, her voiceover delivers the concluding passage of her memoir, romantically pondering what remnants of their relationship might remain after she has departed.

“If I know a song of Africa, of the giraffe and the African new moon lying on her back, of the ploughing the fields and the sweaty faces of the coffee pickers, does Africa know a song of me? Will the air over the plain quiver with a colour that I have had on? Or will the children invent a game in which my name is? Or the full moon throw a shadow over the gravel of the drive that was like me? Or will the eagles of the Ngong Hills look out for me?”

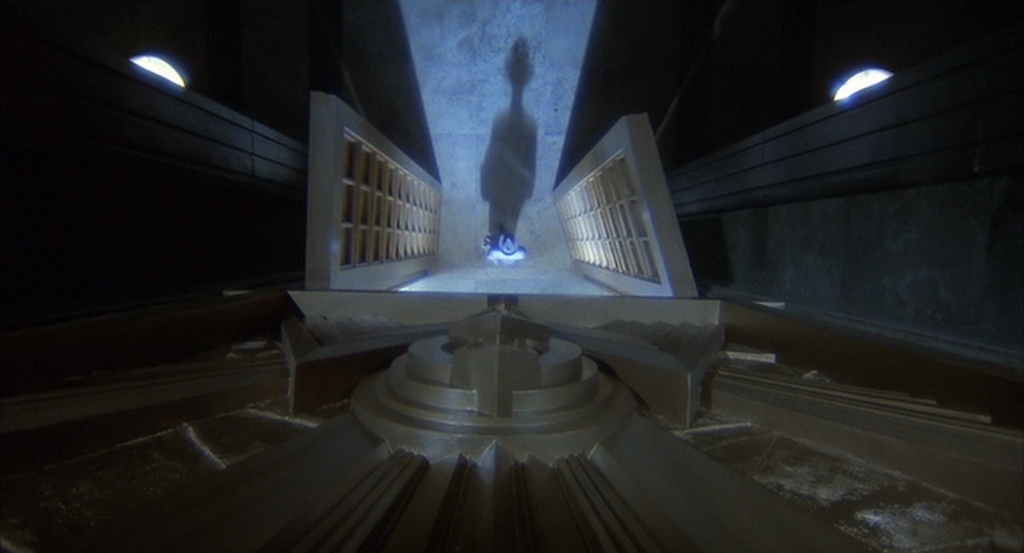

Karen understands that to revere a land as incomprehensibly vast and complex as Africa is to also realise that it will never admire her back, yet through her memory of Denys, Out of Africa preserves a vestige of hope. With her greatest love laid to rest in its rugged wilderness, Pollack’s exquisite final shot points to the remnant of her presence that eternally lingers with his spirit – the respectful, unassuming humility of an outsider, freely exchanging material possession for a divine connection to the Earth, to humanity, and to one’s own mortal soul.

Out of Africa is currently streaming on Binge, is available to rent or buy on Apple TV, YouTube, and Amazon Video, and is available to purchase on Amazon.