Federico Fellini | 2hr 8min

The passengers that gather aboard cruise ship Gloria N. to scatter the ashes of world-renowned opera singer Edmea Tetua are an eclectic mix of European aristocrats. The obese Grand Duke of Harzock is present with his blind sister, a Princess who claims she can see the colour of sounds and voices – besides the General’s, which is drolly described as “a void.” The Count of Bassano is here as well, a reclusive, obsessive fan of Edmea’s who has transformed his chamber into a shrine, and dresses as her ghost to frighten those disrespectfully trying to summon her spirit in a séance. The most dominant demographic by far though are those industry professionals who have come to commemorate their colleague’s passing. Singers, conductors, musicians, and theatre managers have no inhibitions when it comes to showing off their talents on this journey, and consequently expose egos as large as the vessel they travel on.

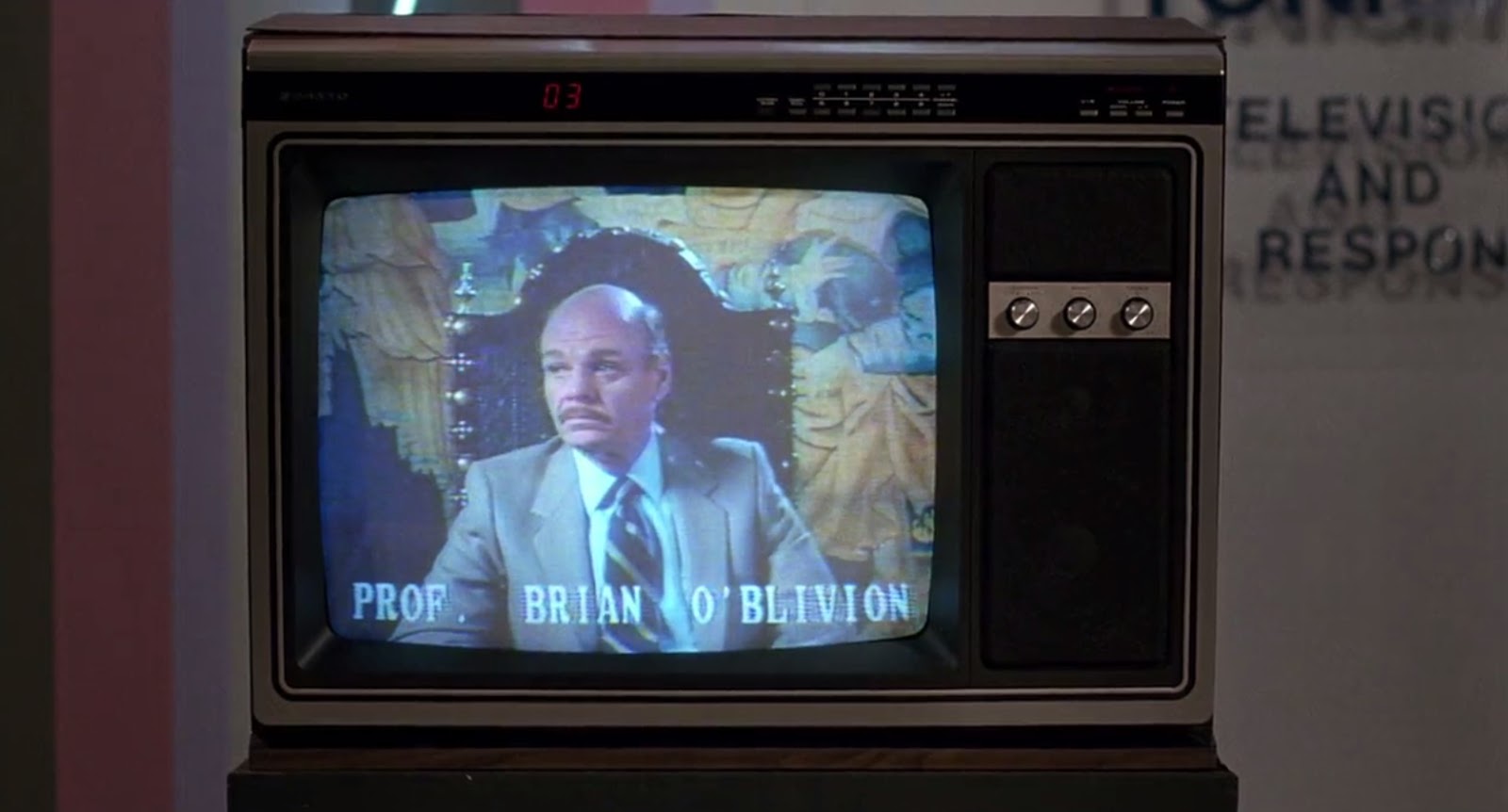

As for our guide through the vast ensemble of And the Ship Sails On, Federico Fellini gives us Orlando, a jovial Italian journalist with a proud dedication to his role of narrator. In the ship’s dining hall of lavish golden décor and architecture, he addresses the camera as both an outside observer and a passenger, while being pushed to the edge of the room by wait staff demanding he stand out of their way. This is a historic moment, he is sure to inform us, though one that is steeped in the absurdity of a ruling class that is no longer answerable to the conventions of mainland society. Here, they amplify each other’s most obnoxious qualities, the singers jealously competing to win the admiration of the crew in the boiler room while nobles squabble over the trivial semantics of metaphors.

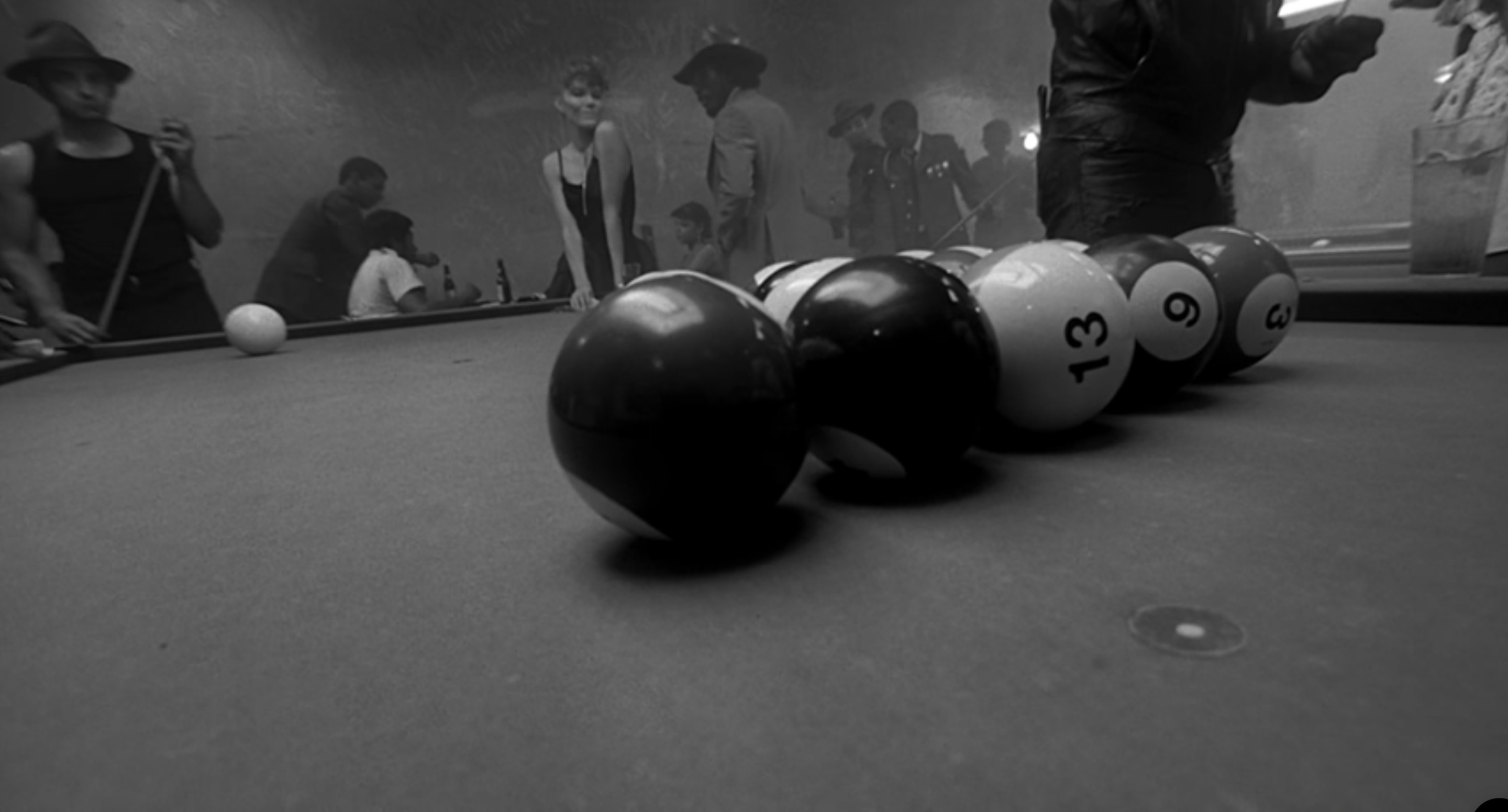

This is an environment of total indulgence and pretence, constructed within an artificial world that Fellini’s narrative bookends expose as his own arbitrary cinematic invention. The recreation of silent cinema which opens And the Ship Sails On mockingly evokes the 1914 setting, using expository intertitles at the docks where characters board the cruise liner, before sound and colour slowly fade in with the reverential boarding of Edmea’s ashes. An even more bombastic shattering of the fourth wall also occurs in the film’s final minutes, where Fellini’s camera tracks behind the scenes of his marvellous set to reveal the crew, technical equipment, and hydraulic jacks rocking the entire ship, stripping away all illusion.

These are Fellini’s attempts to undercut the pomp and circumstance of the voyage, and yet the latter especially comes off as erratic, eroding the formal cohesion of the piece. Where And the Ship Sails On more successfully peels back the layers of this world is in its rich theatrics, revealing the ocean in long shots to be little more than a glittery, blue tarp, and the ship itself to be a miniature model set against painted backdrops. The interiors are equally elaborate, particularly within the golden dining hall where towering candelabras obstruct shots around crowded tables, while even Fellini’s editing resigns his characters to their stations in life. The manic fast-motion of cooks rapidly preparing food decelerates into mechanical slow-motion when it is finally served upon the guests’ plates, whereupon they raise glasses and spoons to their mouths in mindless unison. Without a single line of dialogue, Fellini draws a firm divide between the classes of passengers upon the Gloria N., underscoring the ludicrously dissimilar paces of both lifestyles.

Only when Serbian refugees are rescued and taken aboard in the film’s final act does unity unexpectedly manifest upon this ship, and for some time it would even seem that the optimist in Fellini has won out over the cynic. The blocking here is handsomely staged upon the deck, particularly as celebrations erupt with food and dance shared between passengers from diverse backgrounds. For one blissful night, all pretensions of sophistication are thrown overboard, along with concerns of the very real danger which these shipwrecked outcasts are fleeing from – though the onset of World War I’s geopolitical tensions can only remain at bay for so long.

The arrival of an Austro-Hungarian ship demanding the return of these refugees snaps the passengers of Gloria N. back to reality with jarring whiplash, softened only by Orlando’s hopeful imagining of what might have unfolded had this newfound solidarity also inspired courage. “No, we won’t give them up!” the ship’s singers belt in anthemic unison, using their art to make a bold, powerful statement.

“Death to arrogance,

No monster shall overcome us,

Violence will not conquer us!”

Fellini’s rapid dissolution of this surreal daydream is bleak, and devastatingly inevitable. “The battleship was compelled to arrest the Serbs. It was an order from the Austrian-Hungarian police,” Orlando matter-of-factly informs us, though the conflict does not end here. The Gloria N. was not merely famous for its commemorative voyage, we learn, but for the many lives lost in its catastrophic sinking.

“It’s almost impossible to reconstruct the precise sequence of events,” Orlando continues to monologue as he prepares to evacuate the ship, yet Fellini is not so elusive when it comes to the turning point in this chain of events. In climactic slow-motion, a young Serb refugee lobs a handmade bomb through the porthole of the enemy ship, setting off a chain reaction of events that ends in historic catastrophe. Maybe it was carried in a moment of furious passion, or perhaps it was a premediated terrorist act, Orlando broodingly considers, before his arbitrary musings are swiftly cut off.

All of a sudden, the gentle rocking of the camera which has persisted through the entire film escalates into a formidable lurch, sending fine furniture sliding to the other end of the dining room and effectively destroying these fragile icons of high society. Maestro Albertini conducts the operatic underscore of his own demise upon the upper deck, while The Count of Bassano weeps in his flooded room down below, watching film reels of the deceased opera singer who he will soon join in death.

Still, And the Ship Sails On is far from the mournful tragedy of Titanic, instead drawing a closer comparison to Ruben Östlund’s more recent nautical class satire Triangle of Sadness. Much like his stubbornly upbeat ensemble, Fellini remains cheery right through to the end, his attitude even bordering on careless as he feebly wavers between a few different conclusions without totally committing to any single one. It is quite understandable that he has some fondness for these outrageous caricatures, given that he has essentially instilled them with pieces of his own vanity, though he is also not one to wistfully mourn their losses. After all, within this dreamy microcosm of self-obsessed aristocrats, it is far more enlightening, enjoyable, and enamouring to revel in the macabre absurdity of their splendid misfortune.

And the Ship Sails On is currently streaming on The Criterion Channel.