Ingmar Bergman | 4 episodes (57min – 1hr 32min) or 3hr 8min (theatrical cut)

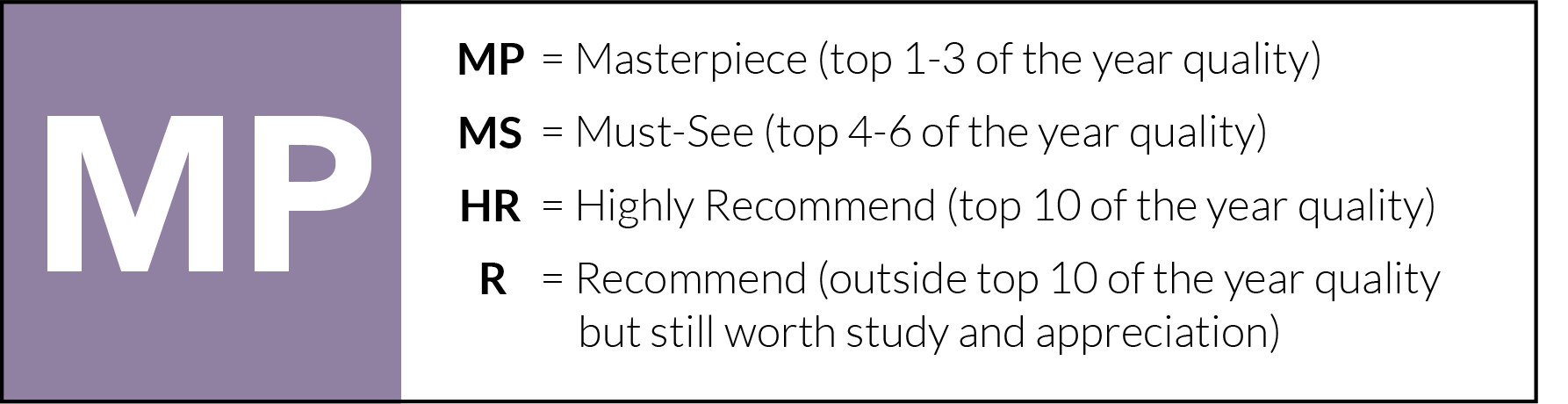

There is a whimsical horror threaded through Fanny and Alexander that only its ten-year-old protagonist has the open-minded curiosity to confront. He gazes in wonder at his toy paper theatre illuminated by nine flickering candles, before wandering around an exquisitely cluttered apartment draped in red, green, and gold fabrics, like a lonely child lost in a world of endless possibilities. He calls out to his family’s maids, but no one replies. The clock chimes three, a set of cherubs rotate on a music box, and a half-nude marble statue in the corner slowly begins to dance. Suddenly, a soft scraping noise emerges beneath the eerie melody, and we catch a glimpse of a scythe being dragged across the carpet. The grim reaper has arrived, but not for young Alexander. Though this magical realist prologue might be the most undiluted manifestation of his vivid imagination, the heavy presence of death underlies all five hours of this Gothic family drama set in 1900s Sweden, marking his childhood with both merciless damnation and divine salvation.

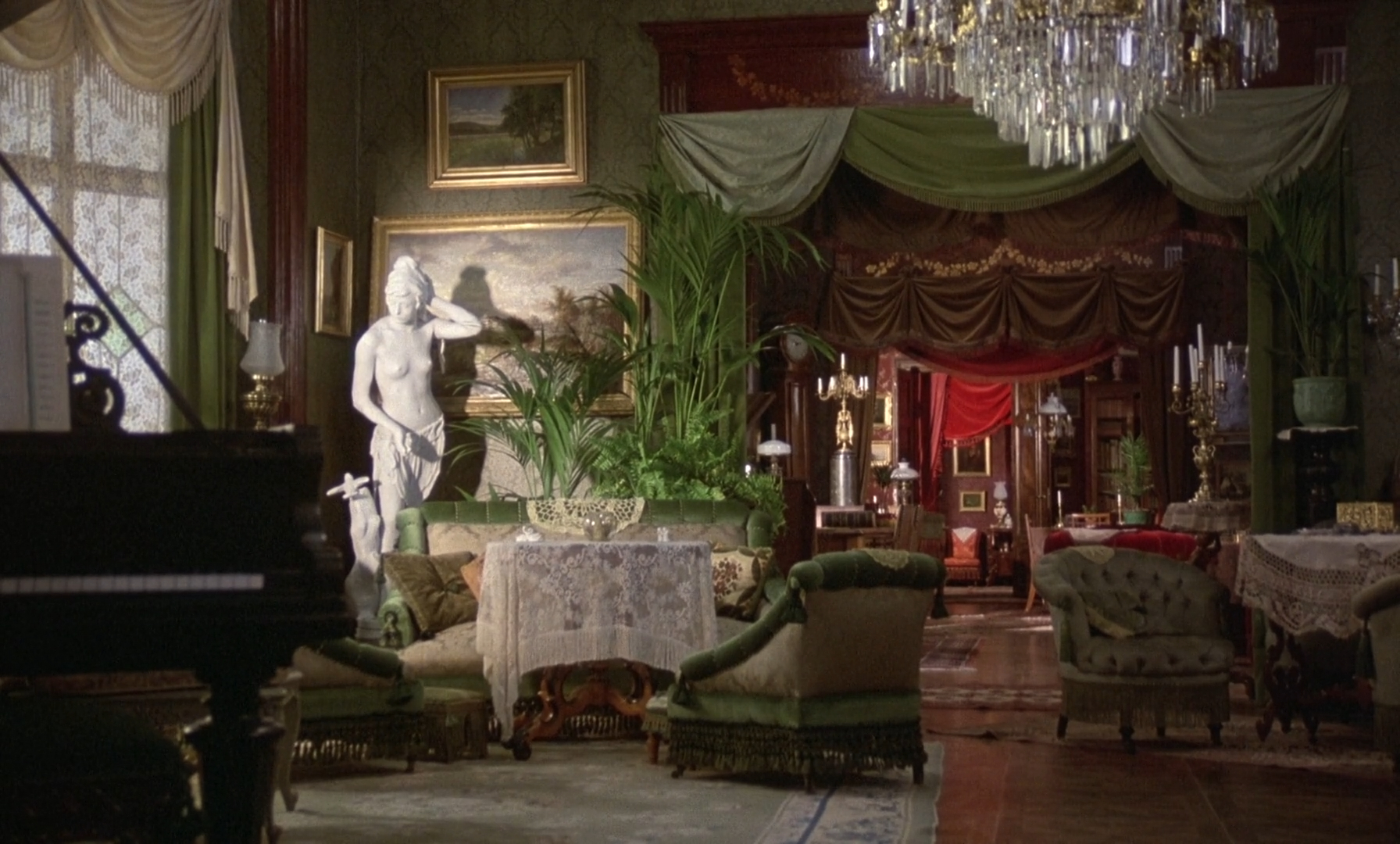

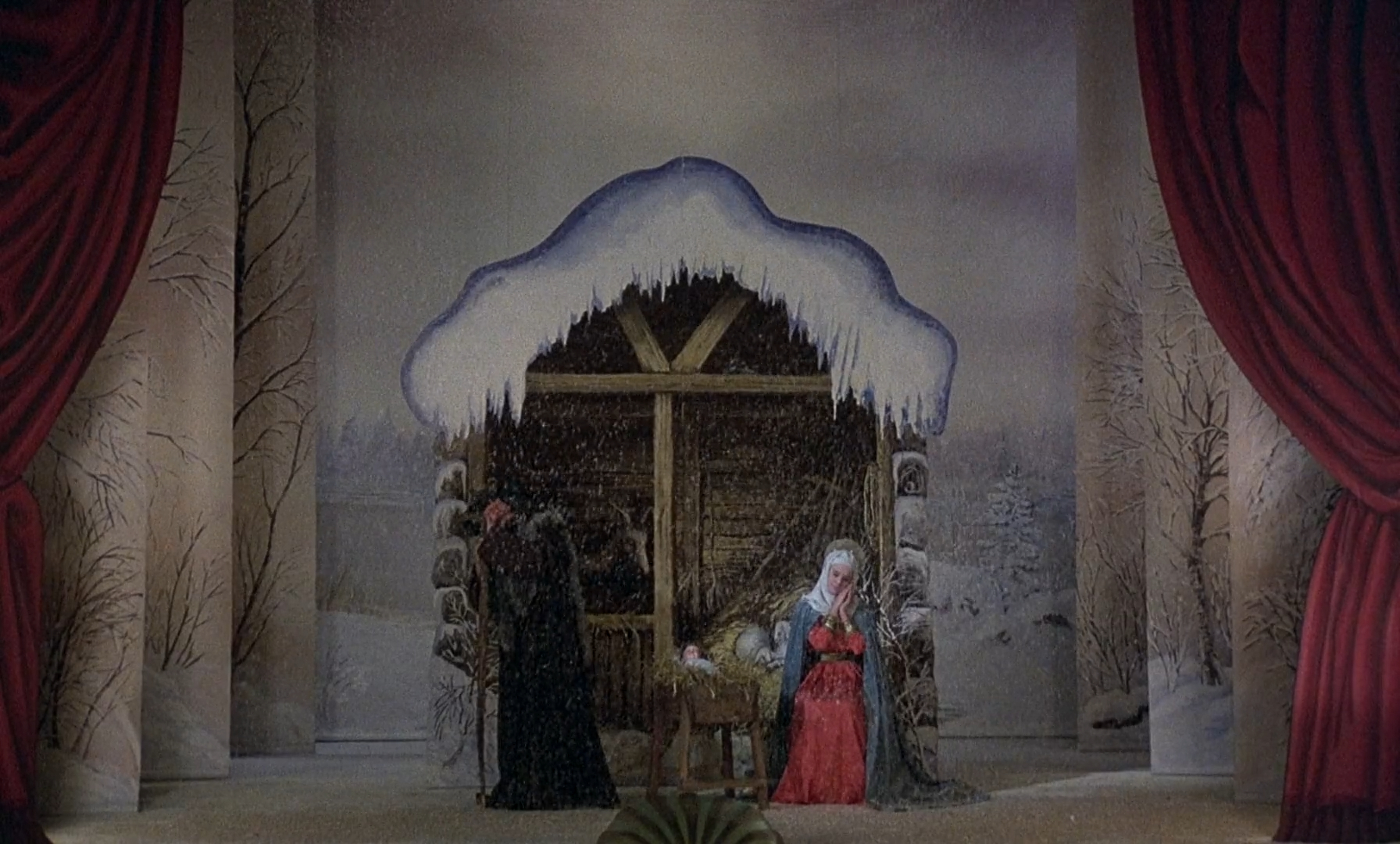

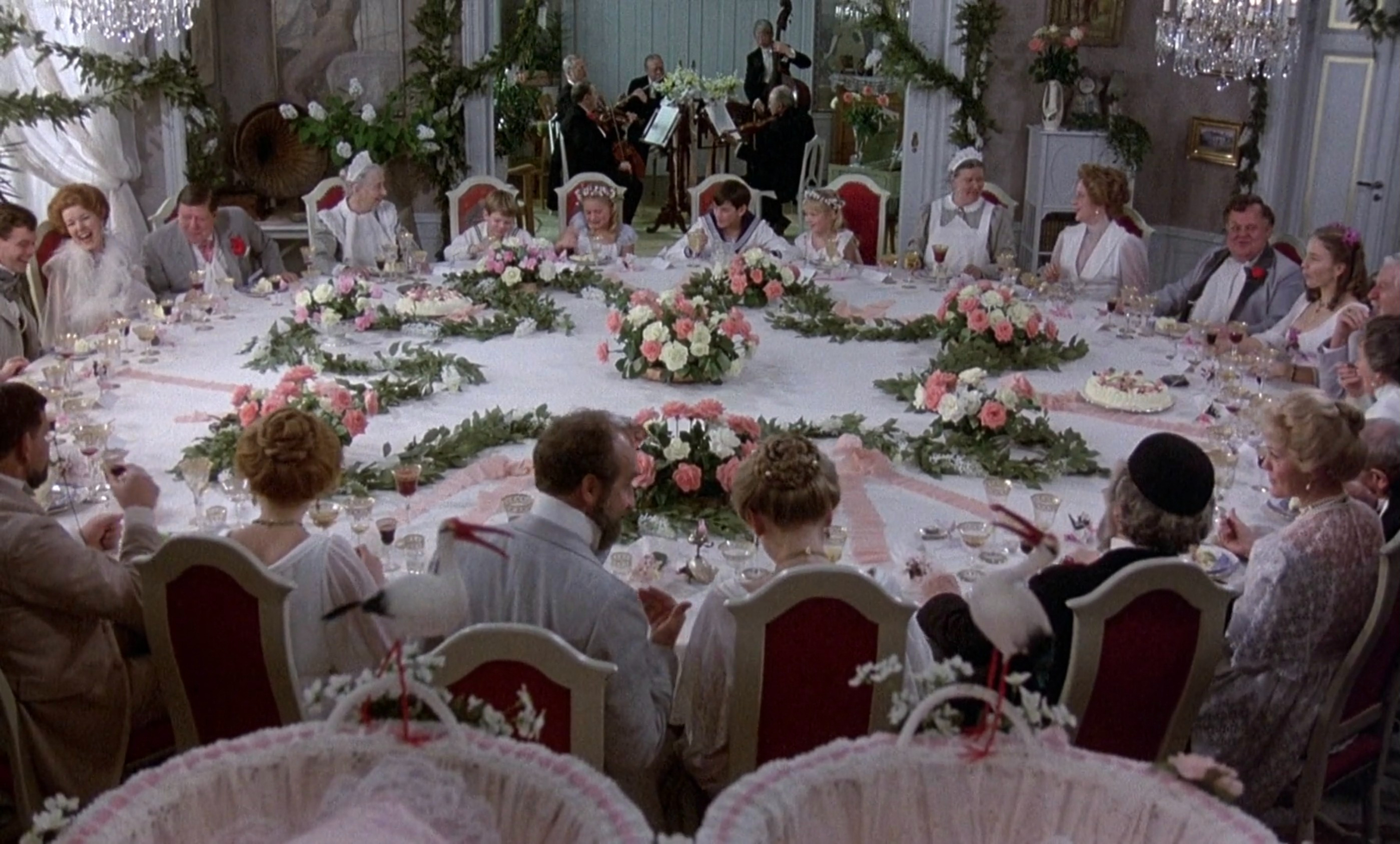

In the haunted Christmastime setting of Fanny and Alexander’s opening, an air of Dickensian fantasy settles over the extended Ekdahl family, revelling in the warm festivities of their annual traditions. Religious celebrations and commemorations form the basis of these gatherings, rotating through the generational cycles of life in funerals, weddings, and christenings. Accompanying these occasions are large meals spread across expansive dining tables, though none are so magnificent as the spread on Christmas Eve night which dominates the first act of the film.

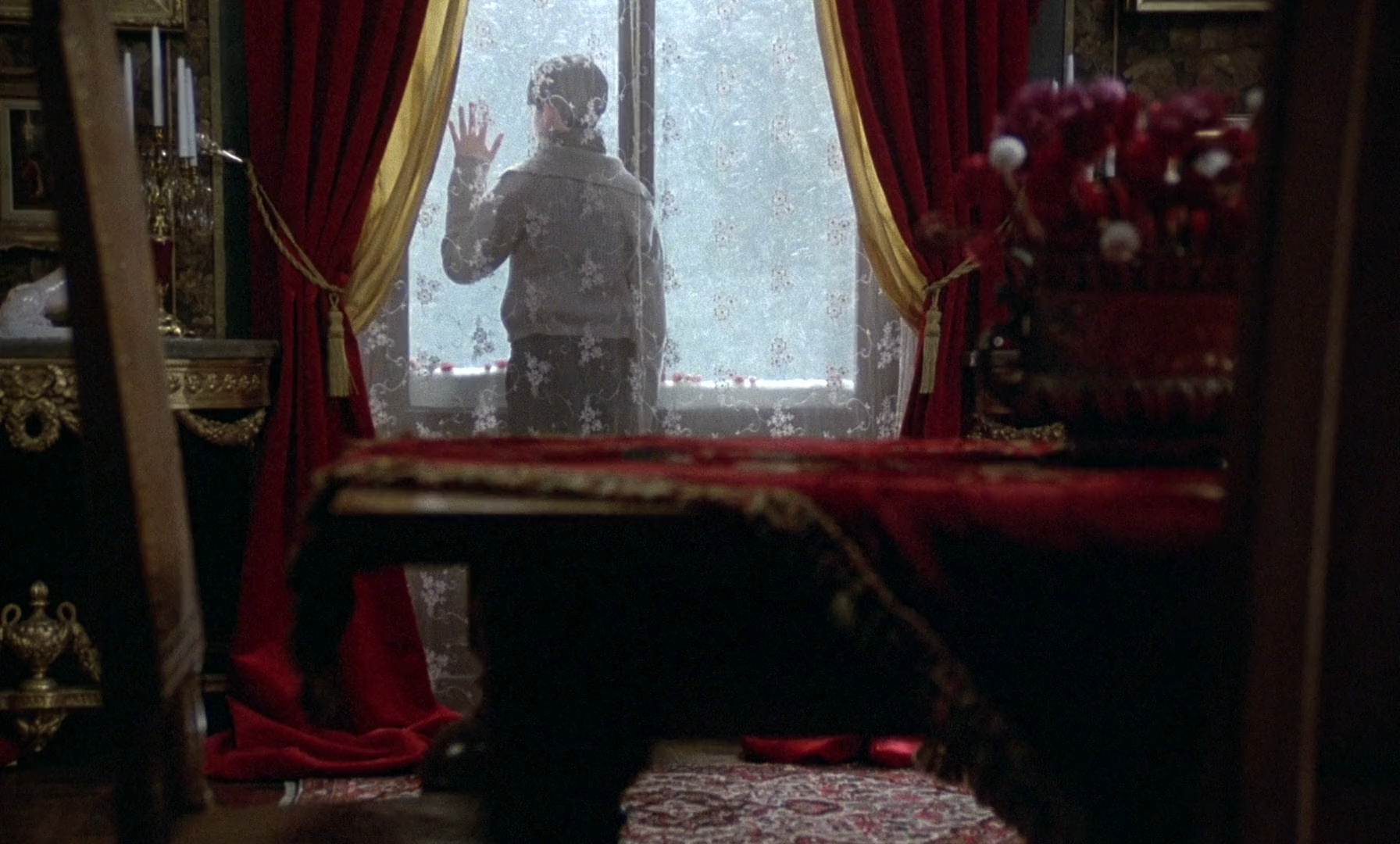

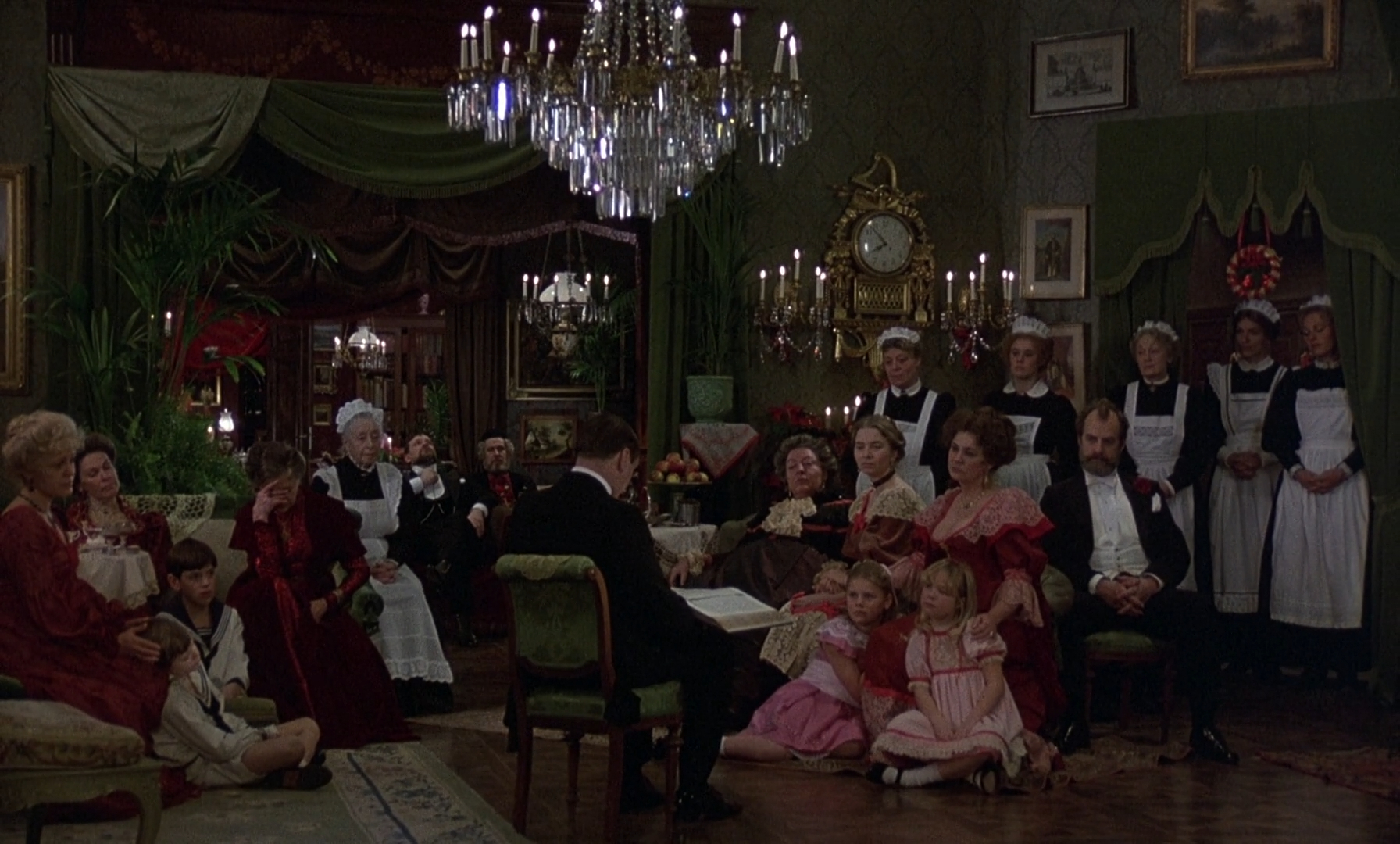

Here, Ingmar Bergman delights in splendidly designed sets of vivid crimson hues, weaved all through the patterned wallpaper, velvet curtains, and holiday decorations illuminated by the golden light of chandeliers and oil lamps. With such profuse warmth commanding the mise-en-scène, there are abundant opportunities to embellish it with small flourishes of emerald-green, popping out in festive wreaths, holly, and indoor plants that snugly crowd out the foreground of his shots.

Matching Bergman’s rich use of colour is his impeccable blocking of a large ensemble, defining the status and identity of each character by their position within immaculately staged shots of family unity around overflowing dining tables and across plush lounges. For all the misgivings and arguments that arise within the theatre-loving Ekdahl family, there is no doubting the intimacy between them as they gather in the vast, splendid apartment of their widowed matriarch, Helena.

It is a lengthy setup which Bergman conducts here, insulating us in these family celebrations like a warm, protective barrier from the freezing snow that blankets the village outside. Within its open living areas, we witness their artistic passion emerge in scenes of poetry recitations and musical performances late into the night, each becoming extensions of the plays they perform for the local community. Between the elegantly draped frames connecting each room as well, Bergman stages them like actors within proscenium arches, turning the apartment into its own theatre brimming with enormous personalities. Even greater depths are revealed behind closed doors, bringing a delicate texture to the family’s joys and troubles – Alexander’s uncle, Adolf Gustav, is a cheerful womaniser with a fragile ego, and Carl Ekdahl possesses significant contempt towards his German wife.

It isn’t hard to see where Alexander fits in here with his elaborate tall tales and instinct to escape into fiction when reality grows too harsh. Right from the film’s first frame of the young child peering into his toy paper theatre, there is a robust formal mirroring between the Ekdahls and their art, manifesting with levity in their lively Christmas festivities, and tragedy in the Hamlet-adjacent death of Alexander’s father, Oskar. It is fitting too that he first collapses during a rehearsal of the play, while he is performing the part of Hamlet’s deceased father. “I could play the ghost now really well,” he jokes on his deathbed, leaving his wife to remarry the cruel Bishop Edvard who presides over his funeral – a truly compelling stand-in for Hamlet’s treacherous uncle Claudius if there ever was one.

The narrative that follows is heavily Shakespearean in both structure and characterisation, though there is also a touch of dreamy self-awareness as Bergman considers the multitude of stories woven into the fabric of his art. “We are surrounded by many realities, one on top of the other,” Alexander learns as he takes refuge within a curiosity shop of puppets, and indeed he seems to possess an imagination that can penetrate each of its metaphysical layers. When the voice of God speaks to him from a dark cabinet, he is filled with a great existential terror and total belief in its veracity, right up until he sees its true form – just another puppet, propping up the artifice of Christian piety.

In this consideration of organised religion as a hollow construct, Fanny and Alexander becomes an act of catharsis for Bergman who, in playing to these archetypes of corruption and innocence, reflects large portions of his own childhood. The fond memories of a flawed but welcoming family exist in stark contrast to the oppressive dynamic that pervades the bishop’s bare, colourless home, and caught between the two is the overly active imagination of a boy who struggles to differentiate between fantasy and reality.

As such, there is also a distinct fairy tale quality that takes hold of Fanny and Alexander, accompanying the introduction of the wicked stepfather with ghosts and demons directly inspired by those religious tales which the children are raised on. Being deprived of a supportive father figure himself, Bergman carries great empathy for Alexander, understanding his immaturity and naivety as a natural stage in his own creative development.

Perhaps it is this lack of emotional inhibition which grants the young boy the means to deal with his grief, letting him lash out in ways which, while not entirely polite, are honest to his thoughts and feelings. In one evocative scene after he hears his mother’s guttural cry erupt from somewhere in their grandmother’s apartment, he creeps out of bed with his sister Fanny to peer through the crack of a door, where they see her wailing in private over her husband’s cold body. Unlike Alexander’s coping mechanisms that are freely expressed out into the world, the overwhelming feelings of adults must be repressed to those small, remote corners where no one else can see. This is a lesson that the bishop beats into him even harder with a “strong and harsh love,” reframing Alexander’s innocent efforts to understand the world as sinister transgressions that will damn him to hell.

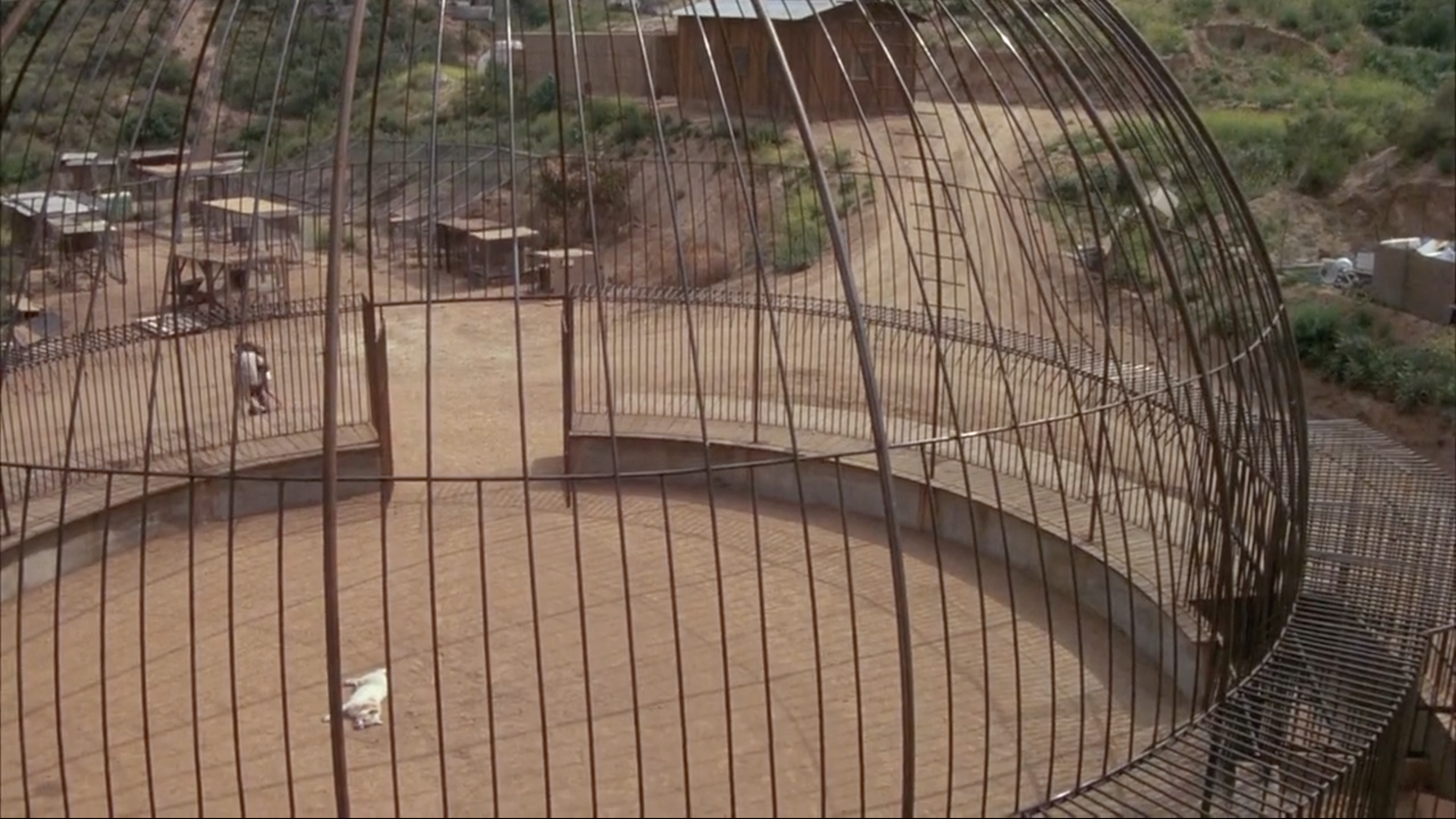

The move from Helena’s vibrant, festive home of expressionistic décor to the stark white halls of the bishop’s Spartan house lands with a quiet dread, and with it comes a shift in Bergman’s blocking. Gone are the large family gathering of characters arranged in relaxed formations across plush couches and dining halls. These rooms are made of stone and wood, unembellished and projecting the bishop’s cold hostility through every communal space. The housemaid, Justina, effectively becomes a scary old witch in this household as well, using the children’s wild imaginations against them through her unsettling cautionary tales. Harriet Andersson refreshingly proves her range here in playing the total opposite of what she represented in her earliest collaborations with Bergman – tedium and severity, in place of youth and beauty.

The grip that both villains hold over our protagonists is suffocating. The bishop’s demand that Emilie and her children lose all their old possessions as if “newly born” is delivered with a faint chill, forcing them to conform to his pious standard of sparse minimalism, and kicking off a long line of attempts to rewrite their identities. Bergman captures this devastating isolation wreaked upon the young siblings with harsh, angular frames, gazing out the windows of their depressing bedroom, and crumpled on the attic’s grey, dusty floor beneath a fallen crucifix, as if slain by a domineering force of spiritual corruption.

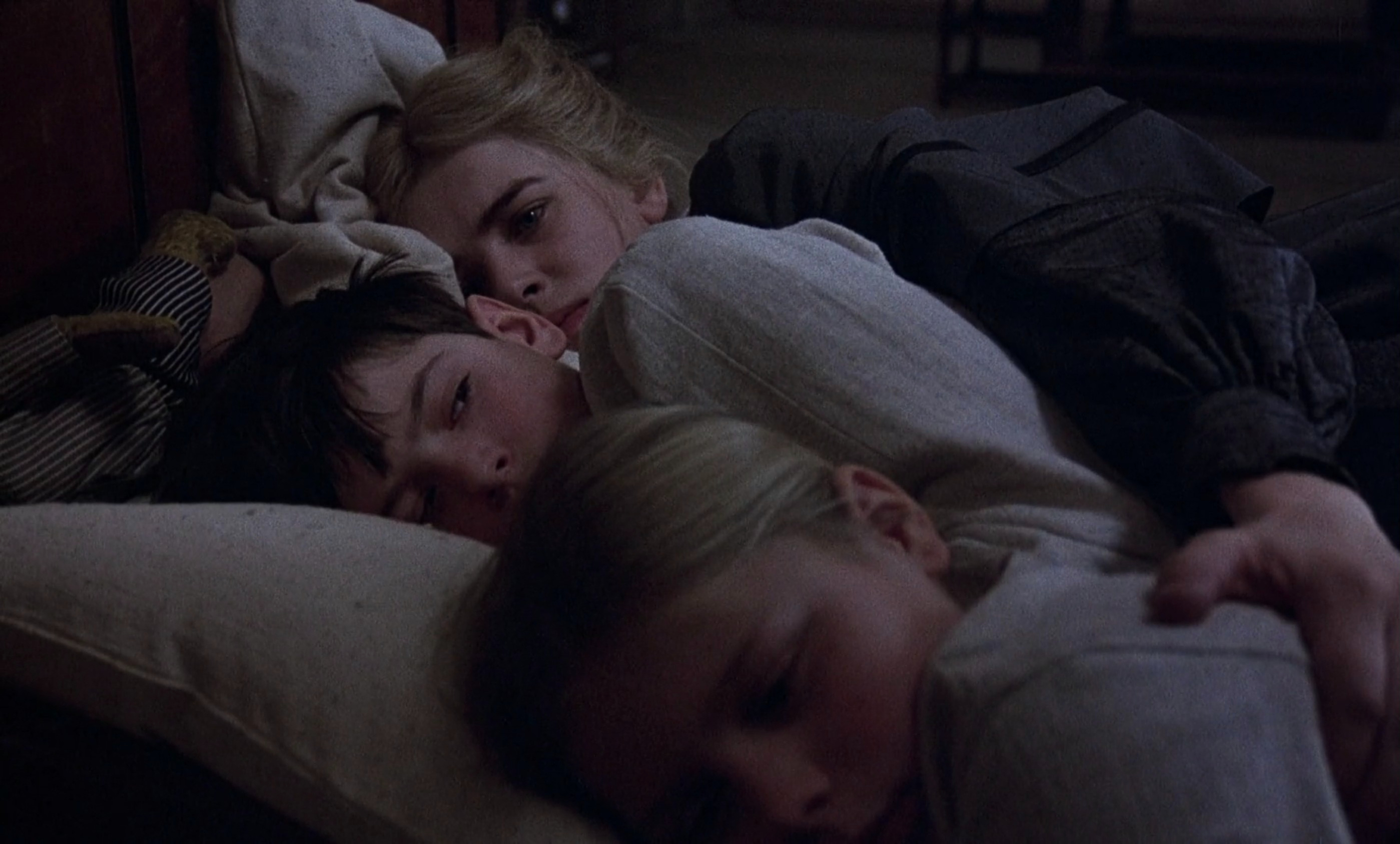

His immaculate staging of his actors goes beyond wide shots too though, as he particularly focuses on the thoughtful arrangements of their faces to understand their joys and frustrations on a psychological, intimate level. As Oskar lays on his deathbed with his face turned to the side, Emilie’s profile leans up against his cheek in pensive mourning, simultaneously revealing both the intimacy of their final days of marriage and the tension that is pulling them apart. In contrast, a later shot at the bishop’s house which frames Fanny, Alexander, and Emilie lying on their sides in bed captures them all looking towards the camera, united in their melancholy. With each face slightly obscuring the one behind it, Emilie is set up at the back as the quiet protector of her children, shielding them from the bishop who stands alone and unfocused in the background.

Jan Malmsjö brings a sadistic venom to this role, though he takes care to only reveal his villainy bit by bit. His first handling of Alexander’s lies is stern but relatively fair, keeping us at a distance from the bitter, angry man who lies beneath the cool veneer. It is difficult to get a good reading of him here, but by the time we arrive at his next chastisement of Alexander, his malevolence is exceedingly clear. In response to the bishop’s degradation and punishment, the young boy grows more obstinate in his disobedience, and yet even he can only stand so many beatings before being forced into submission. Watching on, Fanny silently recoils from the bishop’s touch, and Emilie’s contempt for her husband grows. With all paths of escape cut off, they become a broken, trapped family, suffering in an austere hellhole.

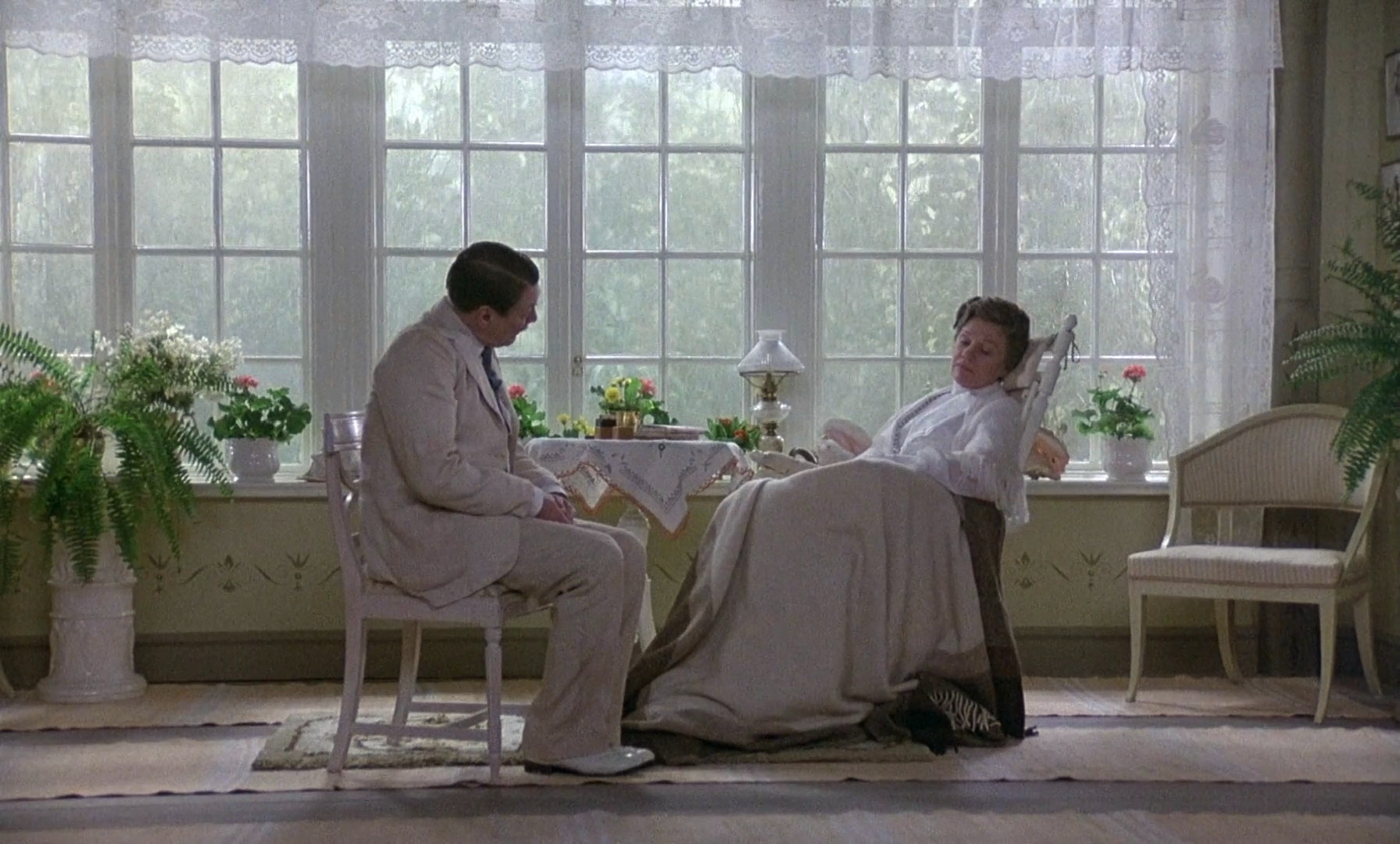

Still, visions of Oskar’s ghost continue to haunt Alexander like reminders of a brighter past, bearing witness to the depression left behind in his wake. These transcendent experiences extend to other family members too, as late in the film Oskar also appears to Helena, his bereaved mother. He speaks little, instead simply becoming the audience to her eloquent soliloquy on the process of accepting her grief, as well as the multiple coexistent truths at the core of Bergman’s dramaturgical metaphor.

“Life, it’s all acting anyway. Some roles are nice, other not so nice. I played a mother. I played Juliet and Margareta. Then suddenly I played a widow or a grandmother. One role follows the other. The thing is not to shrink from them.”

And yet, even as an actress with a deeper understanding of the human condition than her grandson, the pain is no less present.

“My feelings came from deep in my body. Even though I could control them, they shattered reality, if you know what I mean. Reality has remained broken ever since… and oddly enough, it feels more real that way. So, I don’t bother to mend it.”

Bergman’s screenplay flows like poetry through these thoughtful contemplations of life-changing events, bringing this story full circle with the restoration of the family unit. Just as celebrations of Christ’s birth open the film, so too is new life breathed into the Ekdahl clan with the christening of Alexander’s newborn baby sister, reviving the cycles of tradition which connect one generation to the next. Still, even as the conclusion of this epic drama sees the bishop damned to hell in a house fire, four words punctuate its ending with a lingering thread of trauma, keeping his ghost alive in Alexander’s mind.

“You can’t escape me.”

The fantastical imagination of Bergman’s young protagonist is evidently as dangerous as it is enchanting, filtering the world through a lens that distorts every intense emotional experience into a memory that will never fade away. Not only does it manifest as supernatural creatures and visions, but it is also baked right into those dazzling bursts of colour that decorate the fabrics and textures of his family’s home, leaping out like nostalgic recollections of a youth that was only partially lived in the real world. By simply dwelling within this perspective, Fanny and Alexander becomes a deeply sentimental work for Bergman, magnificently distilling his own dreams into expressions of childhood wonder and terror.

Fanny and Alexander is currently streaming on The Criterion Channel, and is available to rent or buy on iTunes.