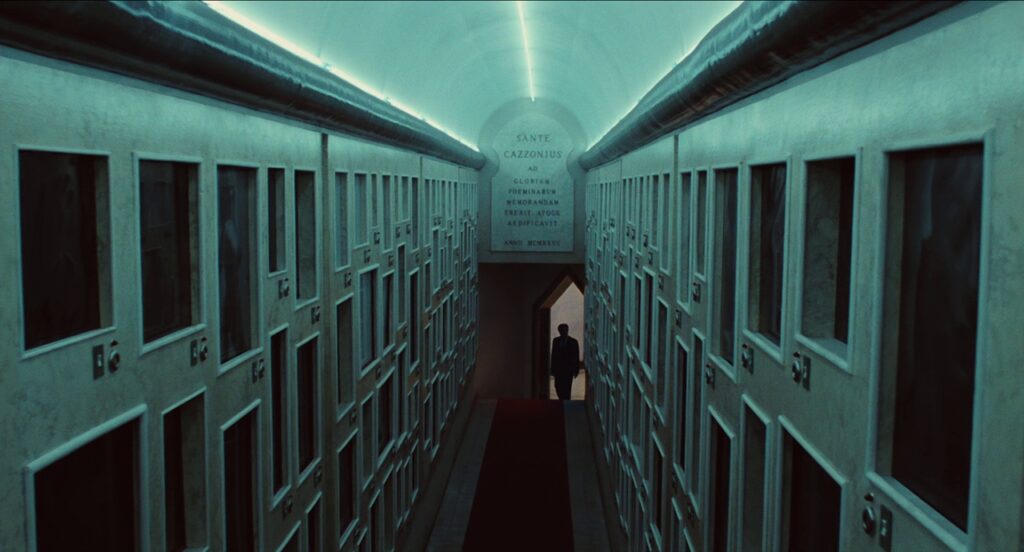

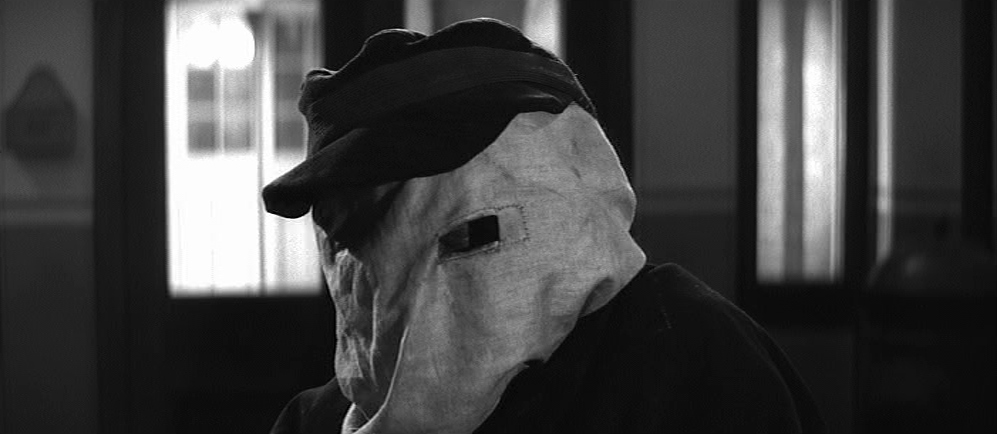

City of Women (1980)

The outlandish matriarchal society that middle-aged philanderer Snàporaz traverses in City of Women is not quite a grand feminist statement, but rather a self-deprecating cinematic tool for Federico Fellini to pick at his own masculine insecurities, sprouting deliberations on gender and sexuality through a string of surreal, chaotic vignettes.