Bob Fosse | 1hr 51min

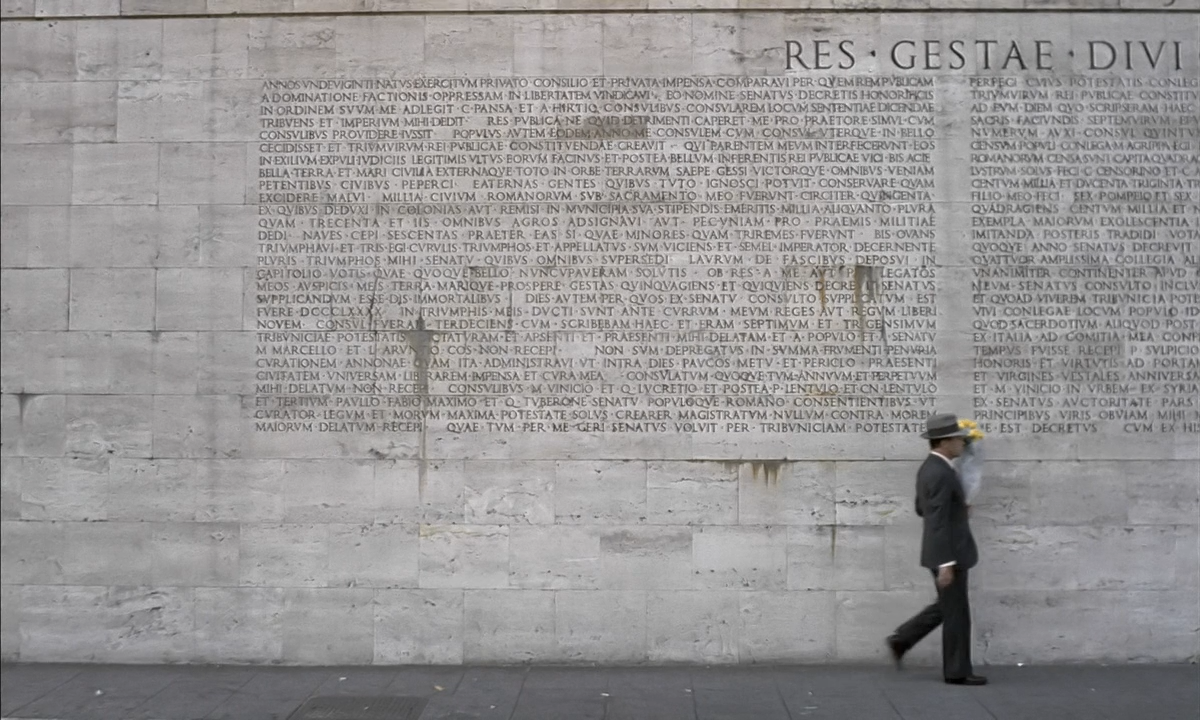

There is something of Lenny Bruce’s rebellious, unorthodox style in Bob Fosse’s 1974 biopic of the comedian’s life which mirrors his own manner, shunning the usual biopic genre conventions to capture the same unruly wit which defined his controversial stand-up routines. Even though his style of black comedy influenced such famous comedians as George Carlin and Bill Hicks, his name is not one often heard today, perhaps since his career preceded theirs by a couple of decades. None of them ever had to wrestle with the same level of cultural conservatism though, and it is in this conflict that Fosse uses Lenny to confront the legacies left behind in the fight for free speech.

It is somewhat baffling that Dustin Hoffman’s performance here is rarely mentioned in the same breath as The Graduate or Rain Man, but evidently Lenny is a little more difficult to digest than either. There is a visible transformation in his physicality and energy, right from Lenny’s early days of bad celebrity impressions to his spiral downwards into addiction, and Hoffman falls into each stage of his life with ease. Most impressive of all is his pure verbosity, leaving audiences hanging on his every word through fast-paced joke setups and then delivering punchlines with a disarming laugh.

But Fosse is always sure to keep a distance from the comedian, looking in from the outside through staged documentary-style interviews with his loved ones and associates trying to make sense of his difficult legacy after his death. In this way, there is a lot of Citizen Kane present in Lenny, and Fosse wields a similarly steady control over this ambitious narrative structure as Orson Welles. What would have otherwise been a rather traditional rise and fall character arc thus becomes an examination of a person who might have always been destined for an early grave, simply due to his own self-destructive tendencies.

Interweaved among these two timelines is one specific stand-up show from the 1960s, in which a bearded Lenny turns his personal struggles into fodder for comedy. Fosse’s editing is a marvel here, as he deftly cuts between dour scenes from the past revealing a failing marriage and a future set that humorously picks apart his own flaws, notably analysing his Madonna-whore complex as well as his proclivity for cheating. There is no doubting his intelligence in the way he analyses his own weaknesses, but it is also evident that his attempts to use comedy as a coping mechanism does little to resolve them in any meaningful way.

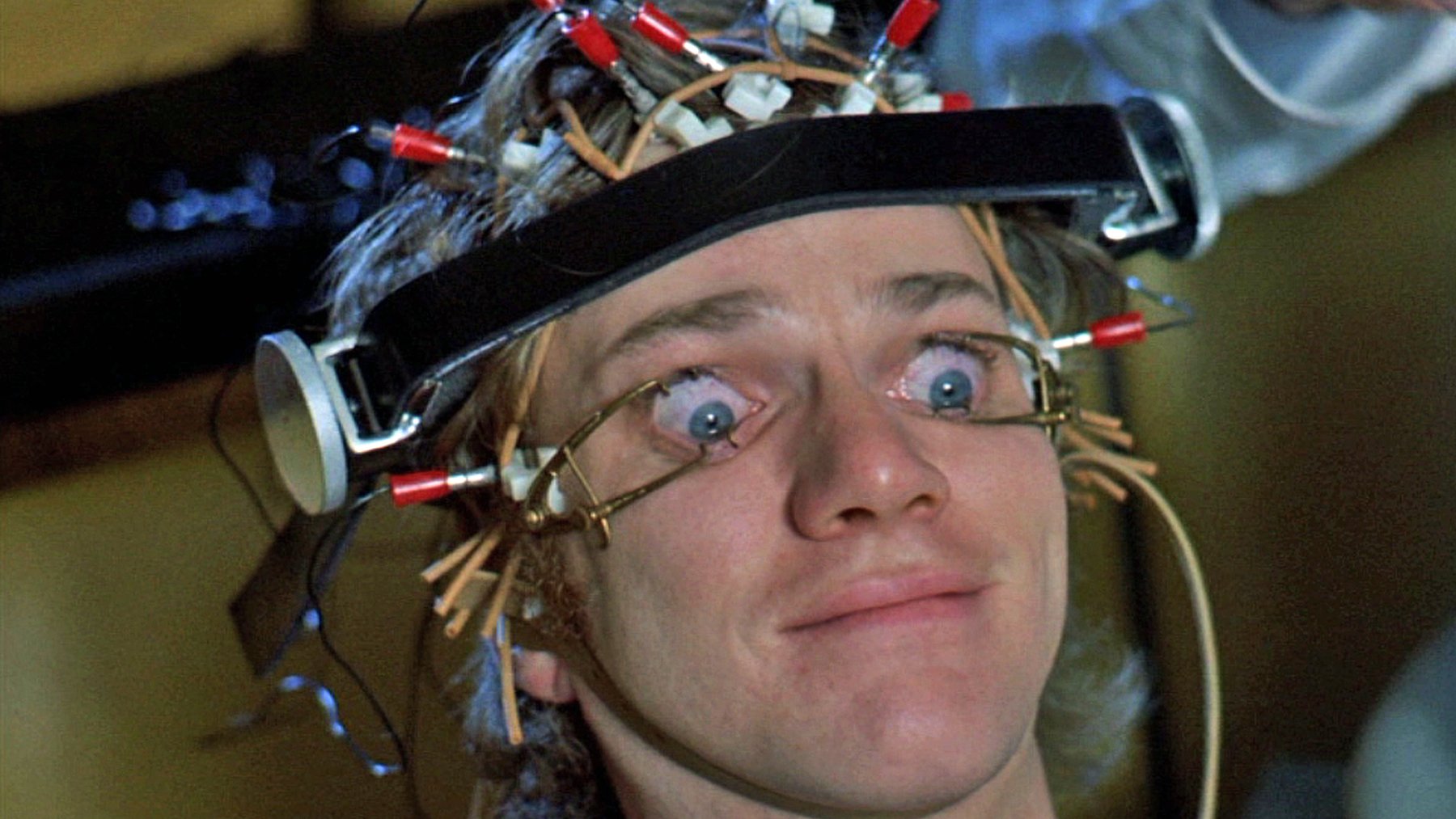

Even within each scene though, there is an energetic rhythm to Fosse’s editing, turning each stand-up show into a sort of call-and-response performance between Lenny and his audience. Fosse’s background in movie-musicals is evident here, as is the influence he would have on Damien Chazelle’s own style decades later in Whiplash, as he ricochets all across Lenny’s stage and catches his laughing audience in close-ups, feeding off the man’s exuberance. After Lenny gets in trouble with the law at one point for public obscenity, the police who start lining the walls of the club become part of this dance as well, and the editing becomes a little more tentative in its velocity. That is, until Lenny takes back control of the room’s atmosphere, slyly pushing the boundaries of censorship while incisively deconstructing the very notion of it, and we find ourselves back at the comfortable, kinetic pace we have grown accustomed to.

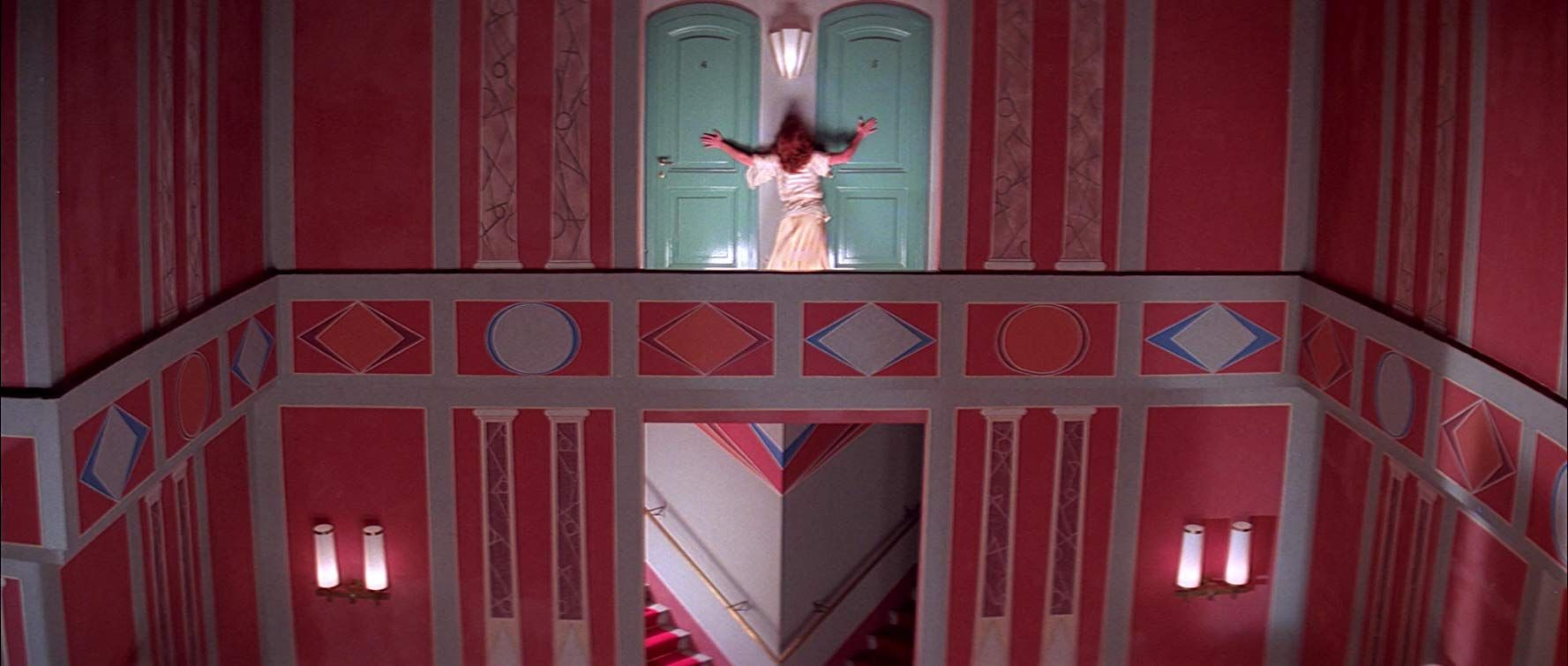

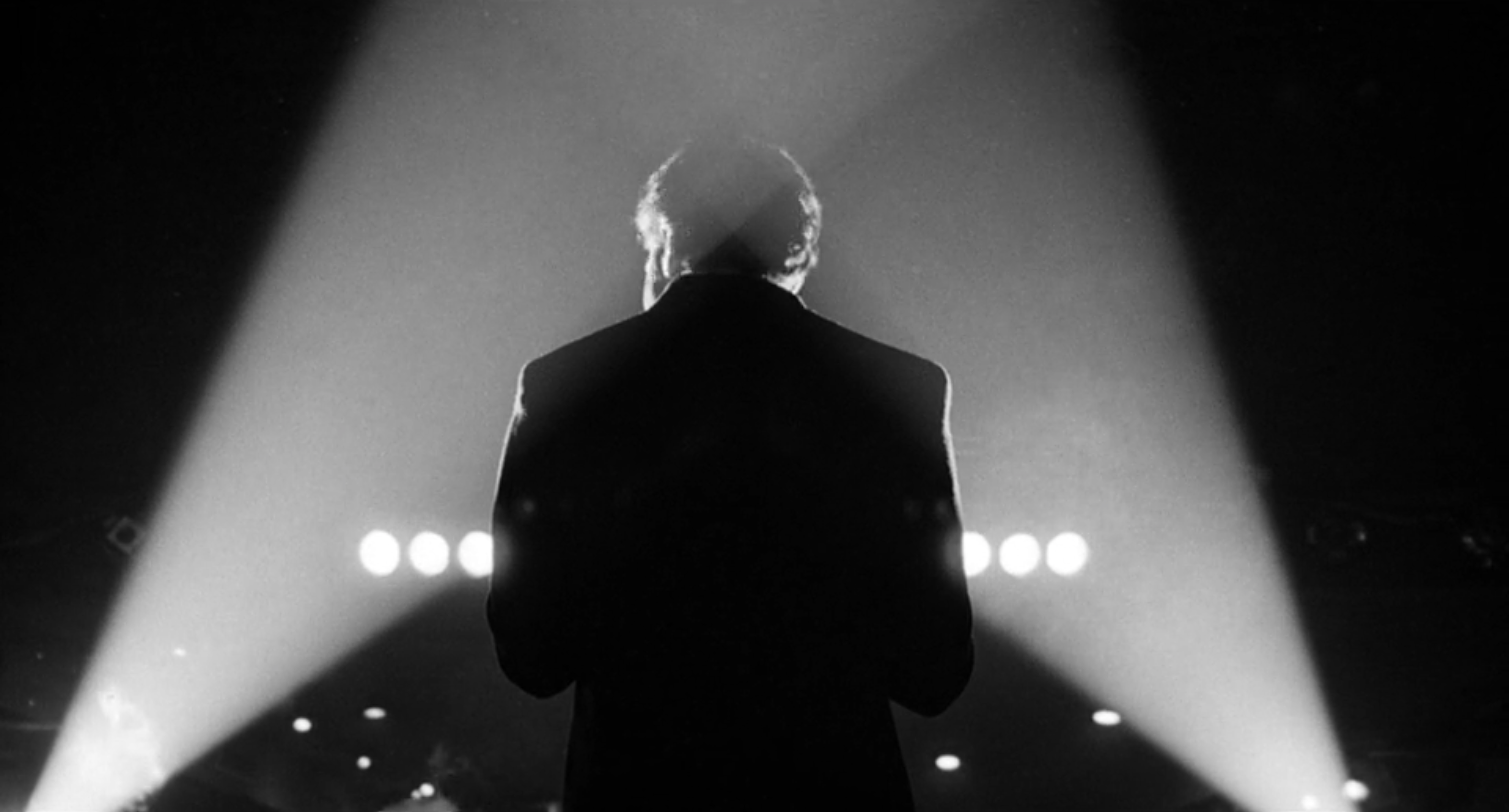

The beautifully lit black-and-white cinematography from Bruce Surtees here shouldn’t be lost in amongst the praise for the editing though. In clubs and bars, pitch black backgrounds are pierced by spotlights centring Lenny as the target of everyone’s attention, bathing him in wafts of smoke floating languidly through the air. Whether he is caught in close-ups or wide shots, everything in these rooms directs all attention towards him, from the blocking of the audience to the framing of the room’s architecture.

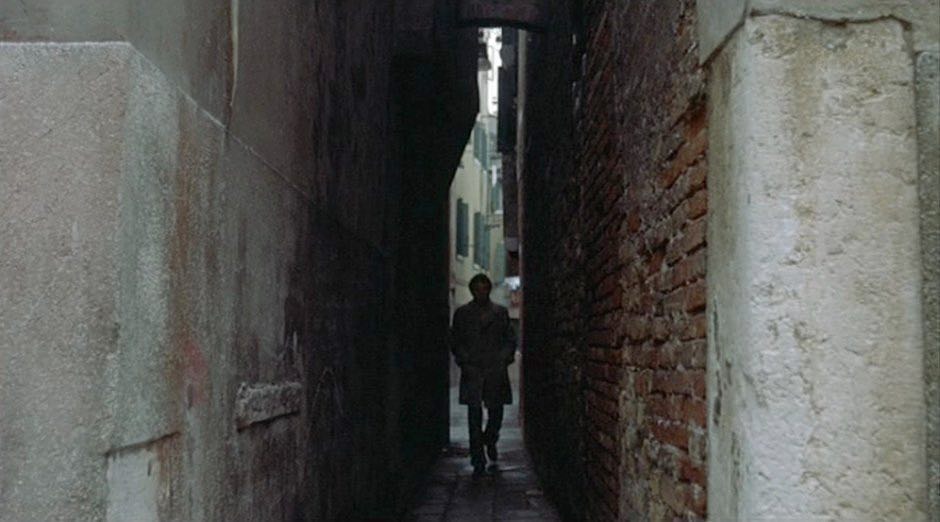

This becomes especially important towards the end in what is certainly the longest take of the film, when a strung-out Lenny delivers a disastrously lacklustre set while high on morphine. No longer are we rapidly cutting around the room or watching excited reactions in close-up, but instead we sit back in a wide and simply observe this barefoot, coughing man in a trench coat mumble his grievances to an unreceptive crowd. The two minutes we remain sitting in this shot feels like much longer, as gradually we begin to notice the silhouettes of audience members get up and leave, and yet we can’t tear our eyes from him.

Given what we have just witnessed, his death that occurs not long after doesn’t come with any great revelation. It is a development Fosse has prepared us for all the way through in the post-mortem interviews, recognising that this bright spark of life could have only ever sustained itself for so long. At the same time though, it is also within this superb narrative structure that his animated verve is kept at the forefront of our minds, as Lenny never stops demonstrating the magnificent power of an act that can reconcile life and entertainment in moments of comedic harmony, no matter how transient they might be.

Lenny is currently available to rent or buy on iTunes and Amazon Video.