Ingmar Bergman | 1hr 39min

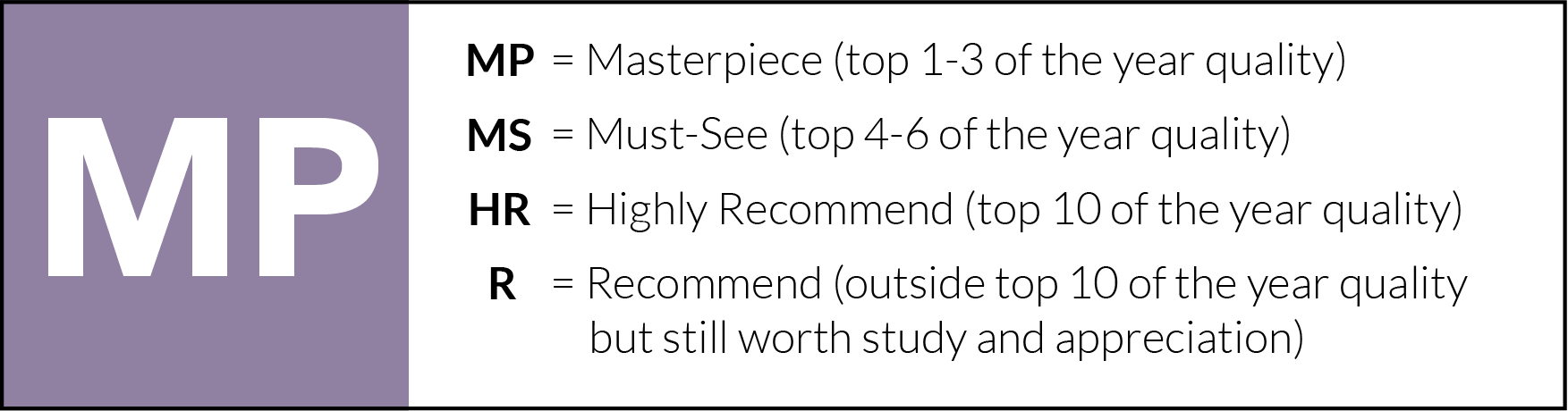

True to Ingmar Bergman’s seasonal metaphors drawn through so many of his films, Autumn Sonata oversees a harvest of the emotional kind unfold in the twilight years of one mother’s life. For the entirety of her daughters’ childhoods, Charlotte has been dedicated to her career as a classical pianist, and held both Eva and Helena to standards as rigorous as those she imposes on herself. Perhaps she has wanted to see them succeed in similar fields, letting them enter the world as even more refined versions of herself, though now with a more mature mind and decades’ worth of hindsight, this does not seem the case to Eva. All at once, the insecurity which haunts Charlotte’s mind simultaneously turns them into similarly flawed copies, and ensures that their successes may never exceed her own. Bergman’s framing of them as echoes of each other represents just as much too, as both habitually grasp at their faces in close-up while Eva levels biting accusations at her mother.

“The mother’s injuries are handed down to the daughter. The mother’s failures are paid for by the daughter. The mother’s unhappiness will be the daughter’s unhappiness. It’s as if the umbilical cord had never been cut. Is that true? Is the daughter’s misfortune the mother’s triumph? Is my grief your secret pleasure?”

For Eva, this grief most prominently manifested in the form of an abortion forced on her at age 18, introducing her to the profound trauma of losing a child that would strike her again many years later in the death of her four-year-old son Erik. So too does she blame her mother’s abandonment for indirectly causing Helena’s severe disability, leaving her paralysed and unable to speak. In the grand scheme of things though, it is the accumulation of subtle, cruel acts which have left the deepest psychological imprints. With a childless void left in Eva’s life, and Helena feeling the absence of her mother, a surrogate relationship has formed between the two that cuts Charlotte out altogether, seeing one sister become the other’s caretaker. Now with Charlotte suddenly visiting their home after many years of silence though, the time has come for her to reap the seeds of misery she has sown – not merely neglecting the wellbeing of her daughters, but wholly sabotaging their attempts to lead happy lives.

Besides the symbolism of growth and harvest that Ingmar Bergman attaches to Autumn Sonata, it is fitting that this is the season he left until last as a figurative representation of his career, having previously used Spring, Summer, and Winter in cinematic illustrations of life’s cycles. At this point he still had a couple more decades of filmmaking ahead of him, including one of his greatest accomplishments in Fanny and Alexander, but the large bulk of his work from the 1980s onward would largely be in television productions that inhibited his creative freedom. As such, Autumn Sonata is located near the edge of his sharp artistic decline, reflecting Bergman’s concerns of old age and mortal regrets in its central mother figure.

Maybe this is also why he finally resolved to collaborate with the last truly great Swedish actress of the era that his path had not crossed yet, Ingrid Bergman. Autumn Sonata marks her final film performance before she would pass away four years later, but even so she makes every minute onscreen count, embodying a severe repression that holds back any displays of maternal affection. Quite significantly, this coldness extends to her music as well. Though her face breaks into soft tenderness while listening to her daughter play the piano, this is not something she can express verbally. Instead, her only remark is an aloof correction of her stylistic interpretation, and a far more refined demonstration of how the piece should be played instead. The way she speaks of music, it might as well be a form of self-punishment, proving her wilful endurance against the temptation to connect with her audiences.

“Chopin was emotional, but not sentimental. Feeling is very far from sentimentality. The prelude tells of pain, not reverie. You have to be calm, clear and harsh. Take the first bars now. It hurts but he doesn’t show it. Then a short relief… but it evaporates at once, and the pain is the same. Total restraint the whole time… The prelude must be made to sound almost ugly. It is never ingratiating. It should sound wrong. You have to battle your way through it and emerge triumphant. Like this.”

On the other side of this relationship too, Ingmar sets up Liv Ullmann perfectly as the daughter dealing with her own repressed pain, only now bitterly recognising flaws in the woman she had been seeking praise from for so long. As Ingrid Bergman plays the same piano piece we heard a few moments earlier with greater technical proficiency, Ingmar captures both their faces in a shared close-up, though it is Ullmann’s defeated expression of contempt, exasperation, longing, and sadness which draws our attention. Very slowly, her gaze slowly shifts between Bergman’s face and hands, recognising how this single demonstration of snobbish superiority captures their entire relationship. When Bergman finally finishes playing, the only remark she can muster up is a feeble acknowledgment – “I see.” She has no words yet to express the emotional isolation she feels from her mother, but by the time the final act of Autumn Sonata arrives, they will start flowing freely like notes on a piano.

In the meantime, verbal expressions of this grating tension are predominantly expressed through monologues in separate rooms. While they independently prepare for the evening meal, Ingmar Bergman intercuts back and forth between their petty jabs, each one imagining what the other is thinking and trying to outsmart them. “Watch carefully how she dresses for dinner. Her dress will be a discreet reminder that she’s a lonely widow,” Eva gripes to her husband, only barely masking her resentment with an air of humour. As if reading her daughter’s mind from across the house, Charlotte mutters her response. “I’ll put on my red dress just to spite Eva. I’m sure she thinks I ought to be in mourning.”

Besides Helena, it is that fourth member of the household who acts as a neutral witness to this malicious dynamic, at times even becoming a surrogate for the audience. Viktor has long grown distant from his wife, dealing with the grief of losing his son far more internally than Eva’s outpouring of emotion, and so within Autumn Sonata he becomes a framing device of sorts who opens and closes the narrative with direct addresses to the camera. He often silently watches from neighbouring rooms, refusing to involve himself in their drama, and it is often this perspective that Ingmar Bergman takes with his consistent framing of actors through doorways, mirrors, and casings.

On one level, these beautifully curated interiors invite us into their warm, orange colour palettes, reflecting the seasonal exteriors in the lighting and décor of Eva’s cosy home. Its inhabitants frequently dress in bursts of red and other earthy tones, and there is even a cosiness to the light clutter of flowers, chandeliers, and striped wallpaper which decorate the mise-en-scène. Still, there is an undeniable harshness to Ingmar Bergman’s blocking, integrating a touch of Yasujirō Ozu’s aesthetic in his rigorous setting of frames in family environments. From this distance, Eva and Charlotte are totally isolated, oppressively bound together within close domestic quarters yet failing to reach any emotional understanding of each other.

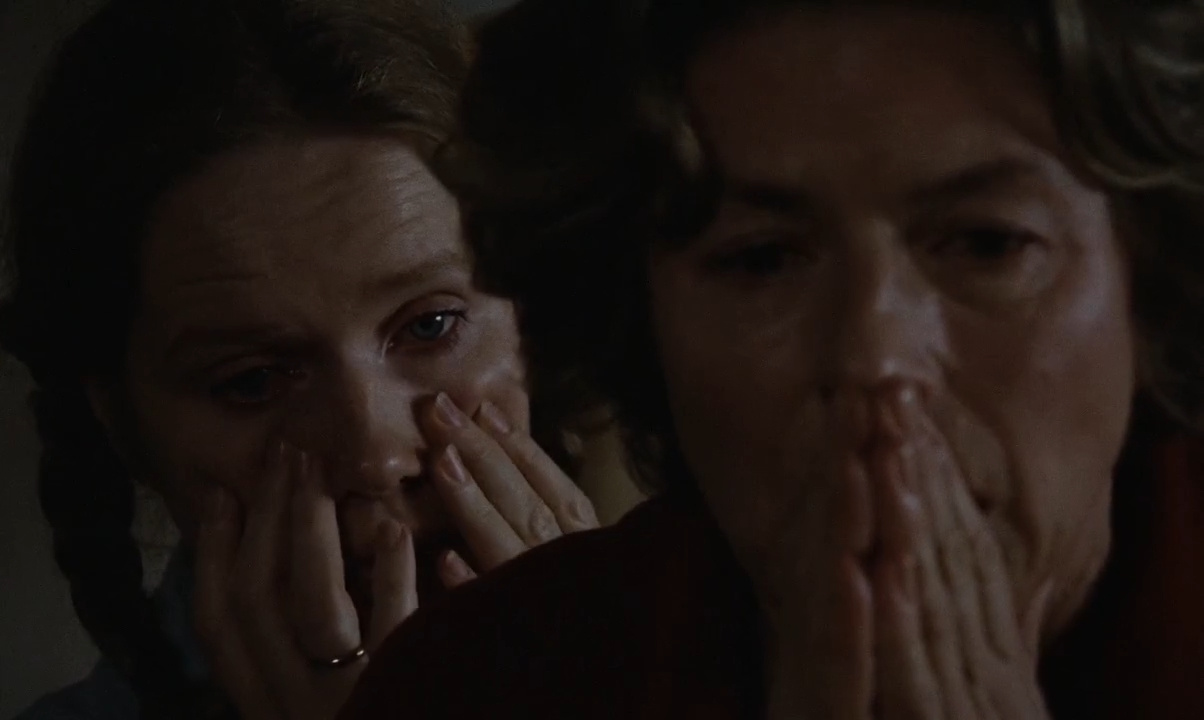

This sense of peering into the lives of this family is magnified even further when Ingmar Bergman slips into dreams and flashbacks, imbuing each with the uneasy surrealism of their repressed memories. Easily the most horrific of all these scenes unfolds in Charlotte’s sleep, unfolding her nightmare of being choked by Eva while she lays helpless in bed, though our brief journeys into their subjective recollections of the past develop a far more wistful tone. Not once does Bergman submit his camera to close-ups when we are in this subjective realm, instead dedicating a single, wide tableau to each scene and thereby refusing to engage too intimately with such sensitive traumas. When a much younger Charlotte shuts herself away to play piano, her daughter waits patiently outside the room, further revealing the unnurtured roots of a relationship painfully captured in one long dissolve dominating the tiny child Eva with a close-up of her mother’s aged face.

When the seal is finally broken on Eva’s wounded silence and the past comes pouring back into the present, there is no longer any holding back the honest anger between both women. “I distrusted your words. They didn’t match the expression in your eyes,” Eva recalls, reflecting on the lie of her mother’s smile when she was clearly mad. Her attempts to live up to her mother’s beauty, intellectualism, and musical talent were never compensated with any sort of recognition. From that desperate insecurity grew hatred, which in turn gave birth to an insane fear, clearly stunting her emotional growth which has echoed through to her adult years.

Although Eva is effectively reduced to the mentality of a distressed child in her sobbing, there is at least a conscious connection being formed for Charlotte when, for the first time, she embarks on her own self-reflection. She too recalls her childhood where she was never touched by her parents, whether out of affection or punishment, and so she turned to music as a form of expression. She did not want to be a mother, she confesses, desiring to be held rather than the one who does the holding, though Eva does not hesitate in calling out the obliviousness of this desire.

“I think I wanted you to take care of me… To put your arms around me and comfort me.”

“I was a child.”

With Charlotte’s cold, stone heart finally breaking and recognising the trauma that has spread from one generation to the next, Ingmar Bergman almost gives us hope that there may be some change on the horizon for both women. Quite despairingly though, it only takes until the next day when she is on her way back home that old habits and attitudes rear their head, summoning them back into the toxic cycles which originally drove them apart. As far as Charlotte is concerned, she can’t be that terrible a person – after all, she plays concertos with warmth, and she isn’t at all stingy. Even more painfully, Eva has completely reverted into her submissive desperation for acceptance, resolving to write an apology letter to her mother.

“Dear Mama, I realise that I wronged you. I met you with demands instead of affection. I tormented you with an old hatred that’s no longer real. I want to ask your forgiveness.”

Ingmar Bergman’s characters may be cruel and cowardly, but this is not a barrier to establishing empathy in Autumn Sonata. He has the utmost compassion for those who have experienced the profound depths of the human experience, emerged as maladjusted individuals, and faced up to their repressed desires and insecurities, even if they are unable to reconcile them with their outward expressions. Like the persistent rotation between immaculately framed wide shots and close-ups, and the seasonal changes which echo across his broader filmography, both mother and daughter here are trapped within cycles set in motion several generations before either were born. At the root of all emotional and psychological problems in Autumn Sonata, Bergman simply finds the inescapable reality of a past we never had any control over, inextricably connected to our defiant, tormented humanity.

Autumn Sonata is currently streaming on The Criterion Channel, and is available to rent or buy on Apple TV. The Autumn Sonata DVD can also be purchased on Amazon.