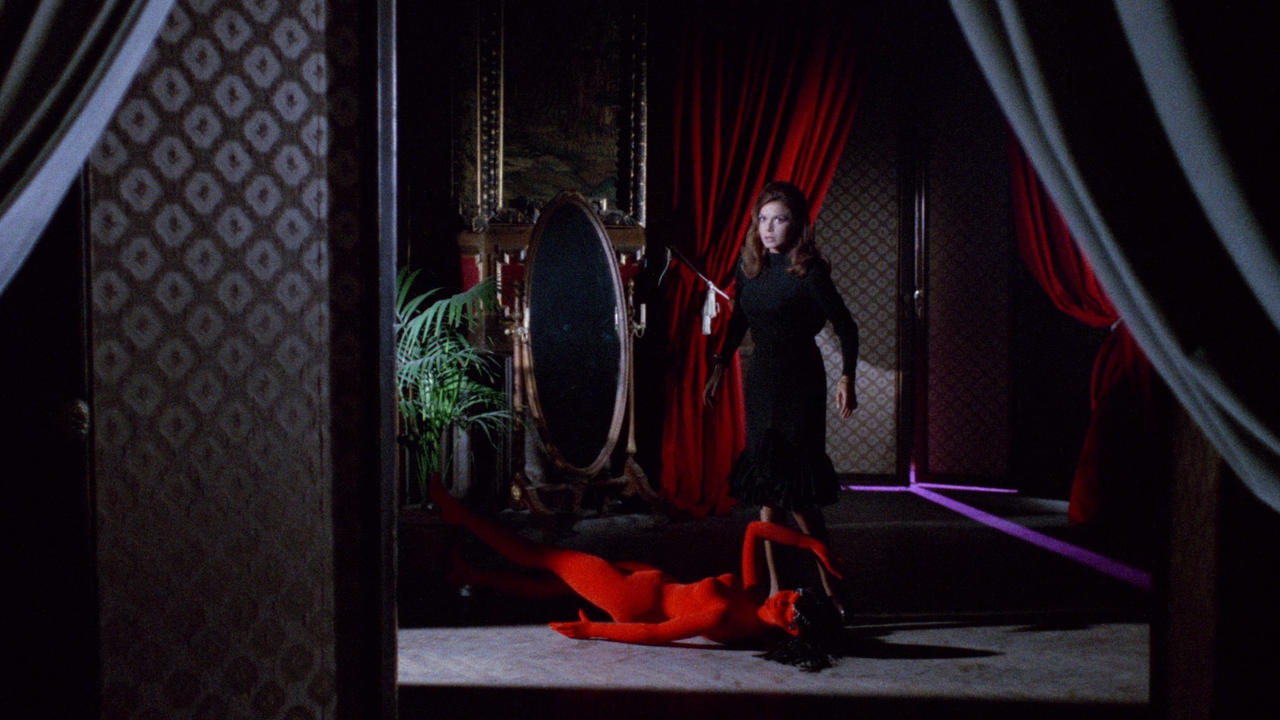

Blood and Black Lace (1964)

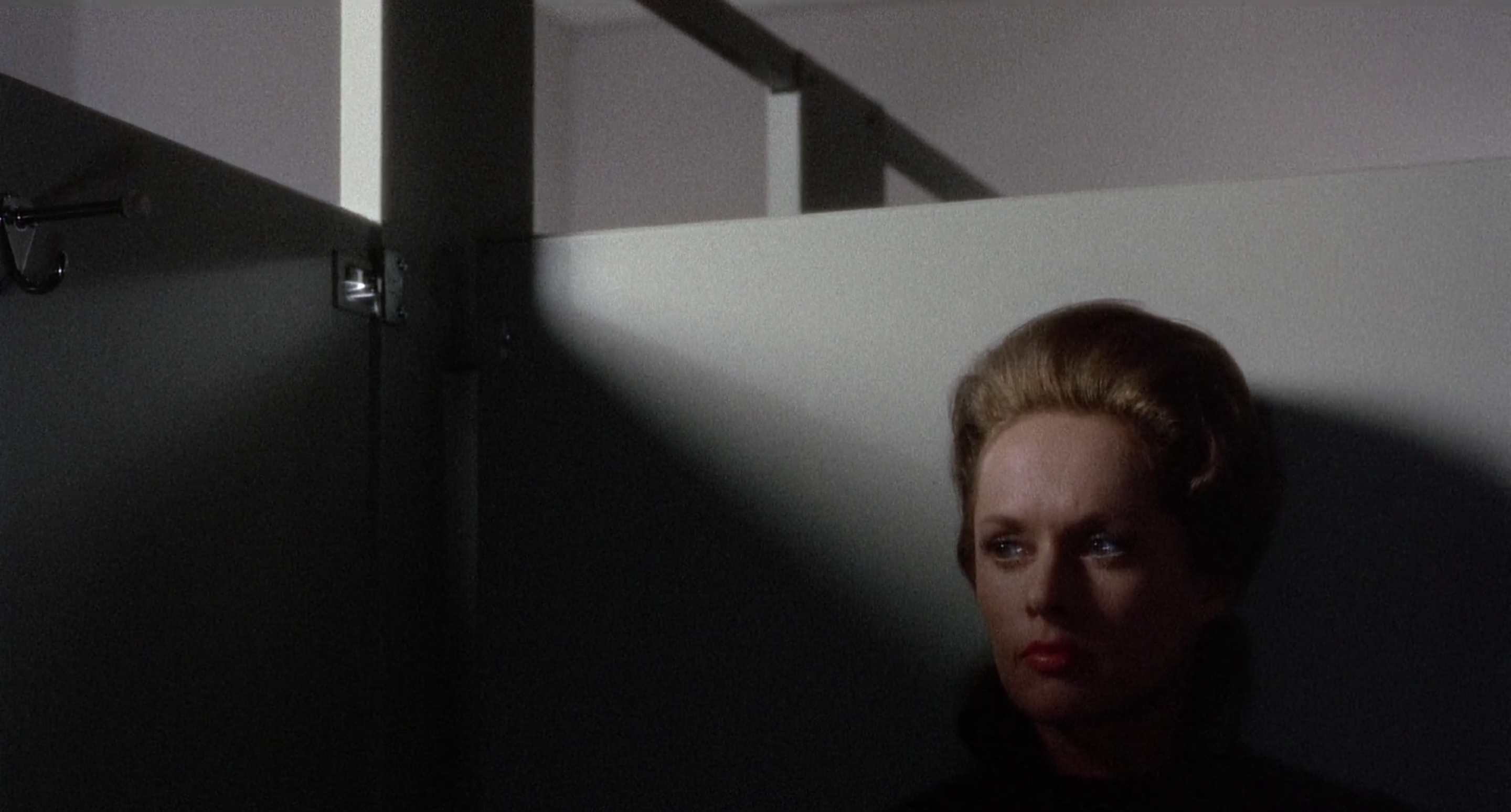

An inconsistent artistic paradox like Blood and Black Lace is hard to reckon with, but for all the flaws in its pulpy writing there are a thousand more strengths in Mario Bava’s audaciously stylistic direction, turning an Italian fashion house into a Technicolor fever dream where horrific murders explode with vibrantly expressionistic sensibilities.