Sergio Leone | 2hr 12min

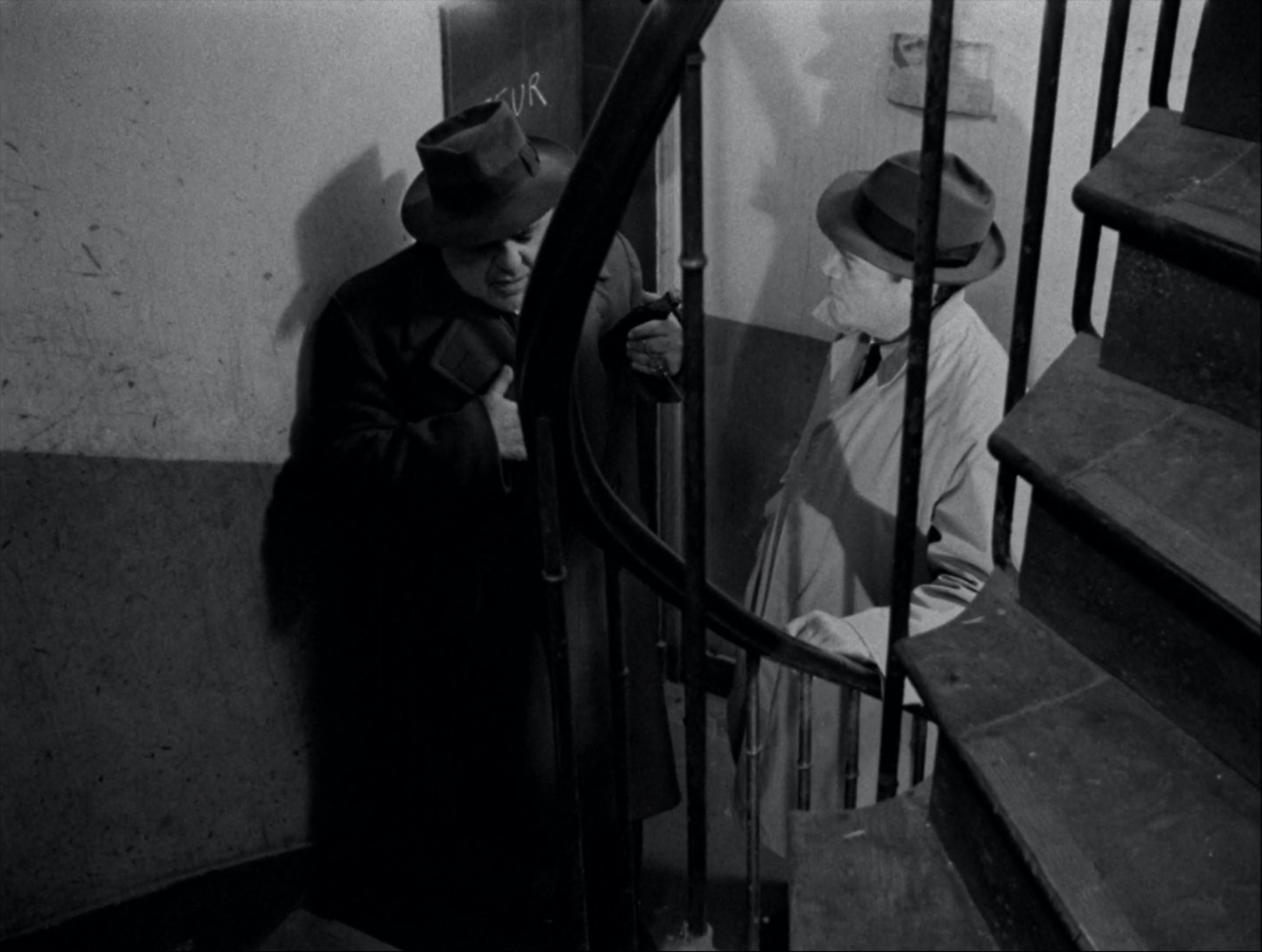

Few words are exchanged by rival bounty hunters Manco and Colonel Douglas Mortimer when they finally come face to face in the rural settlement of El Paso. For the first fifty minutes of For a Few Dollars More, Sergio Leone has been intertwining their paths in search of escaped bank robber El Indio, each scoping out their common target while remaining largely ignorant of each other’s presence. From their raised vantage points on either side of the main road, they spy on the outlaw’s gang gathering outside a bank, before incidentally turning their telescope and binoculars on each other. That evening, Manco sends the porter to packed Mortimer’s belongings and bring them outside where he is waiting, consequently leading to the pivotal confrontation that will ultimately decide the fate of both their quests.

Ennio Morricone’s score is sparse here, though the few notes he does play unite a pair of musical motifs. When we cut to Manco, a flute skims through a terse, cautionary phrase, while the Jew’s harp we have come to associate with Mortimer reverberates a piercing twang. The Colonel is framed in the classic Leone shot between Manco’s spread legs, before they take turns scuffing each other’s shoes. As much as this peacocking is an attempt to mark their territory, the prospect of either backing off seems increasingly unlikely, especially when they begin shooting at each other’s hats to prove who is the better gunslinger. The editing is taut, but with Morricone’s majestic score largely absent, we recognise that this sequence is not building to one of his deadly quick draws. From this rivalry, a begrudging respect is born between Manco and Mortimer, who soon begin negotiating the terms of their professional partnership over drinks.

This willingness to cooperate may be the greatest virtue which our heroes possess in For a Few Dollars More, contrasting heavily against the villain’s treacherous manipulation of his own gang. El Indio acts purely on greed and self-preservation, stoking mistrust among his henchmen in the hopes that they all end up murdering each other. If he and his lieutenant’s plans work out, then he need only split the loot they have stolen from the bank two ways.

Unfortunately, El Indio’s shrewdness is not so forward-thinking. The fracturing of his gang drastically weakens his position against Manco and Mortimer, placing him in a precarious position by the time their final showdown arrives. In the Old West, this choice between unity and division is the only shot anyone has at finding order in anarchy, and may be all that stands in the way of life and death.

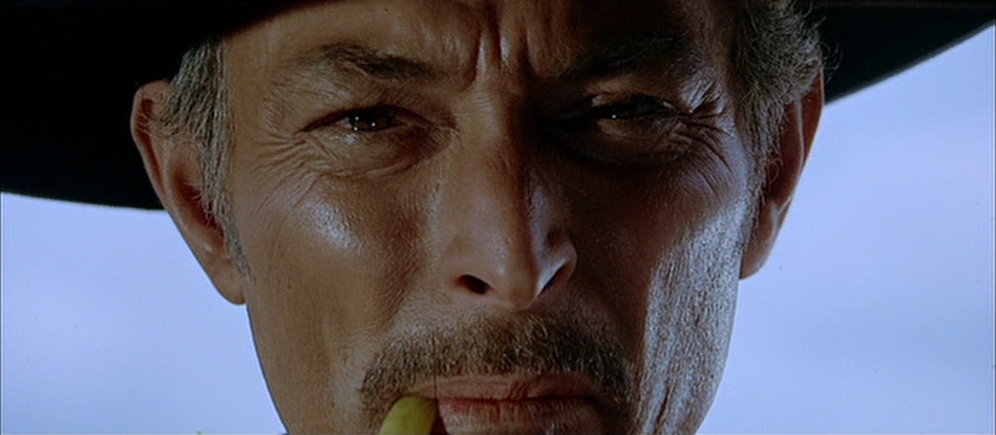

After the extraordinary hit that was A Fistful of Dollars, it was only natural that Leone should continue probing these blurred binaries of Americana. With twice the budget, he is no longer restricted to a single location, but rather sprawls his narrative scope across multiple settings and expands his ensemble. The only point of continuity to carry over between films is Clint Eastwood as The Man With no Name, informally recognised here as Manco, and this time sharing the lead role with Lee van Cleef. Together, they form a stoic duo as they infiltrate, outsmart, and outshoot El Indio’s gang, seeking to claim the bounty that has been placed on the bandit’s head.

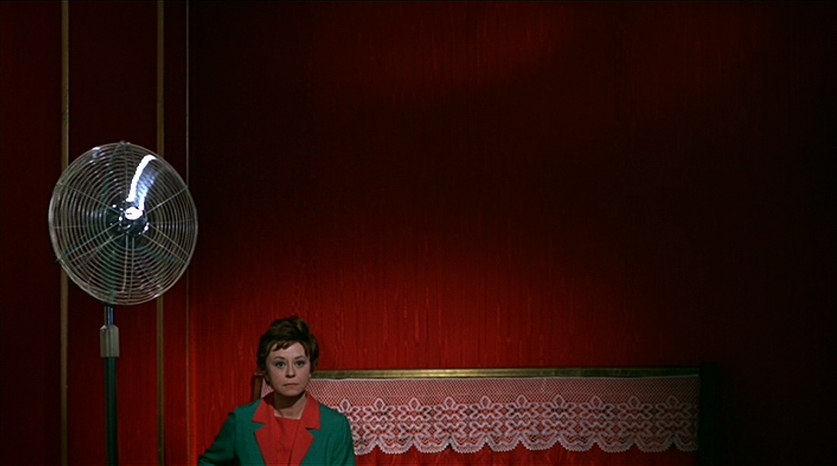

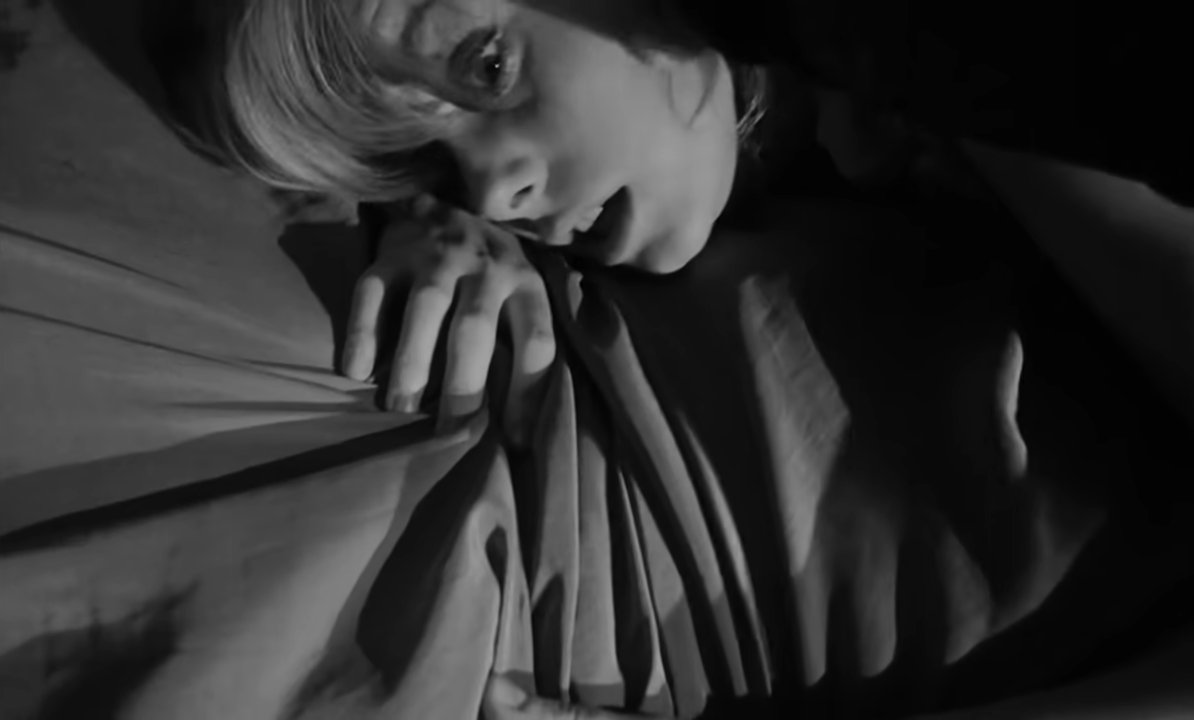

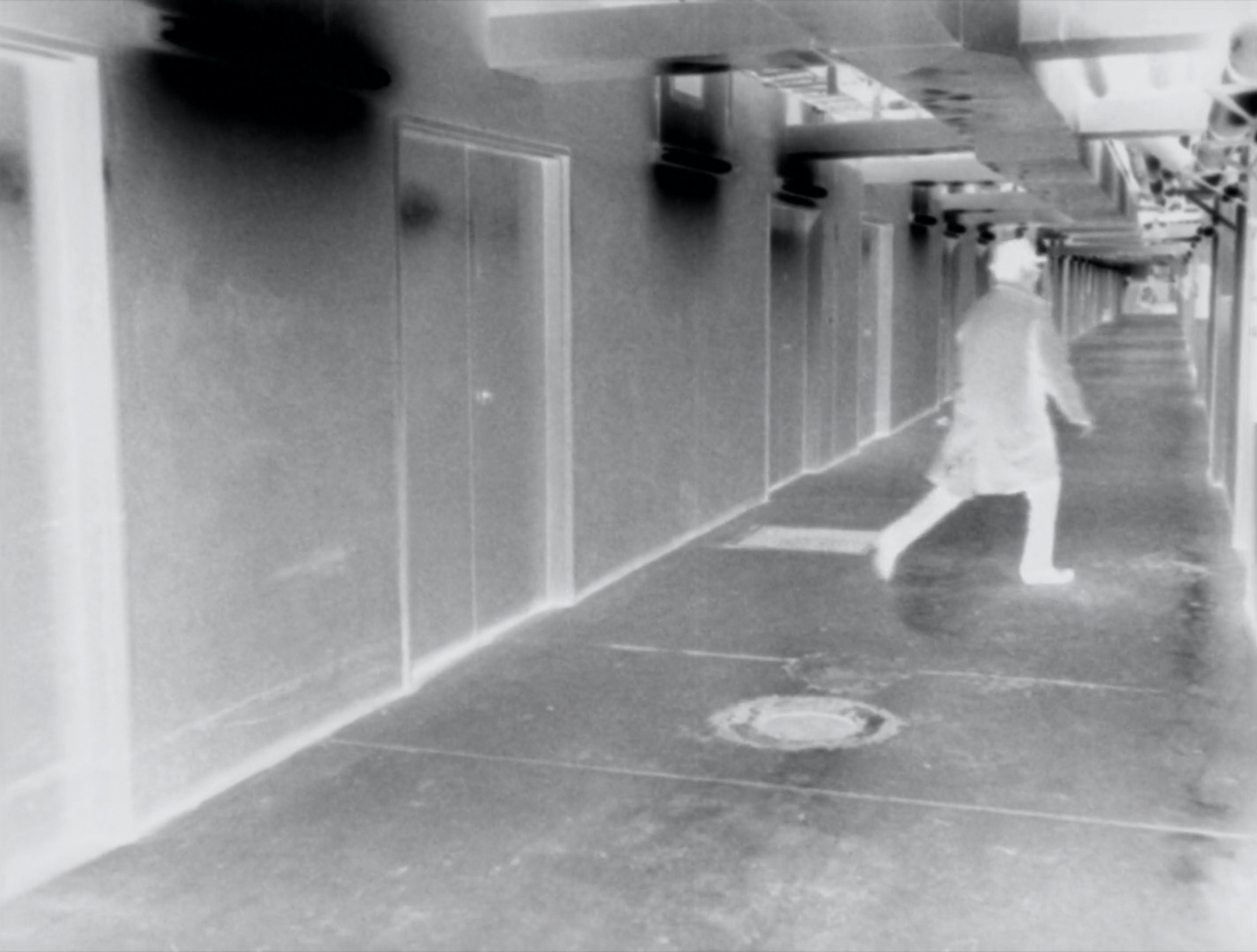

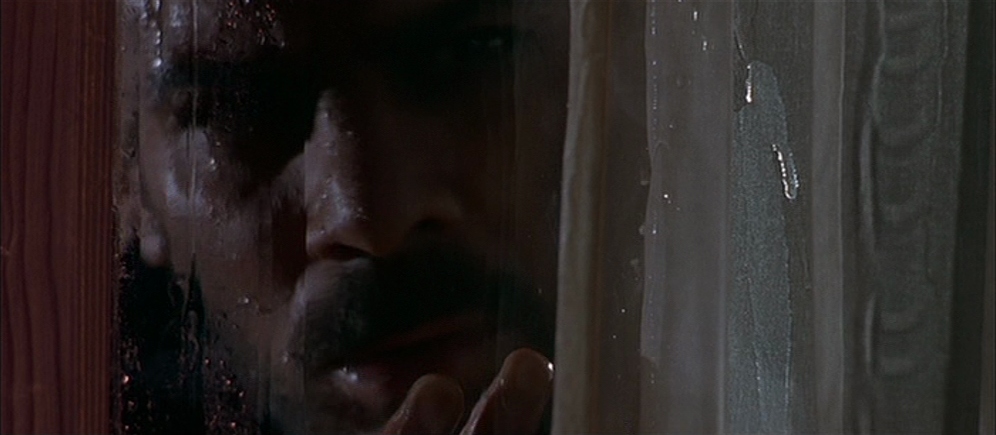

Despite this narrow character link between A Fistful of Dollars and For a Few Dollars More, there is no doubt that both films inhabit the same dusty, lawless world of Leone’s American frontier. Far from the polished black-and-white cinematography or the blazing Technicolor beauty of classical Hollywood Westerns, this sequel maintains the faded colours and coarse textures of its precursor, using the natural rugged terrains of the Spanish desert to stand in for the harsh Texan wilderness. The only moisture to be found in this environment is that which drips down the faces of Leone’s actors, pressed up against the camera lens in deep focus close-ups that simultaneously track the action unfolding in the background.

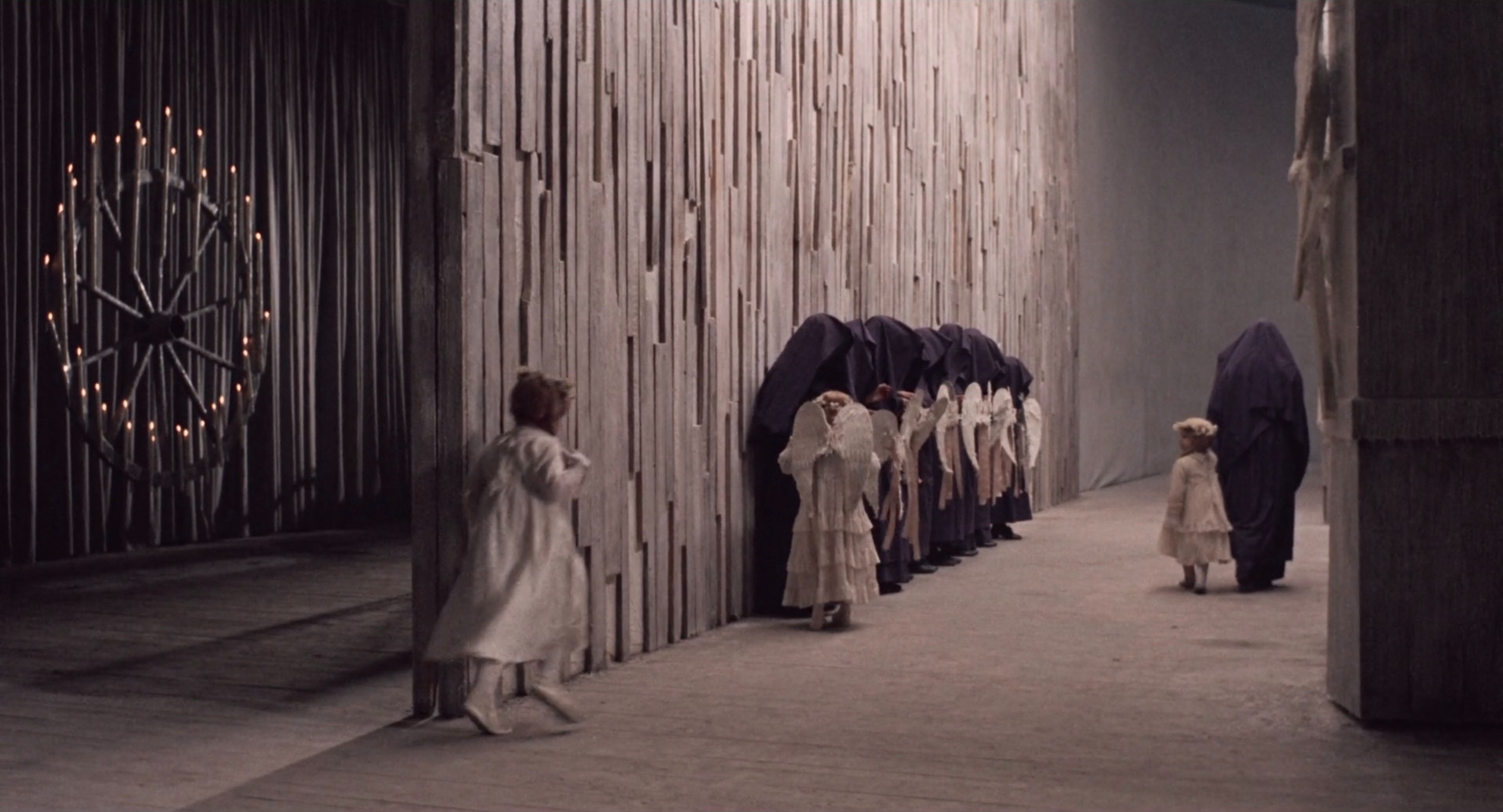

There is much tension to be drawn from such lively staging, layering shots with dynamic motion and nervous stillness, though it is once again Leone’s editing which most crucially navigates each moving part of his staggering set pieces. Beyond even his John Ford or Akira Kurosawa influence, Leone’s montages call all the way back to Sergei Eisenstein, patiently cutting between twitching hands, holstered pistols, and apprehensive faces as they anticipate an outburst of action. Suspense is also rife in his constant cutaways to the safe that the gang is planning to steal from the bank, while the rapid cutting between Mortimer’s eyes and El Indio’s wanted poster when the bounty hunter first learns of his prison break lands like bullets, binding their destinies together in a cacophony of gunshots.

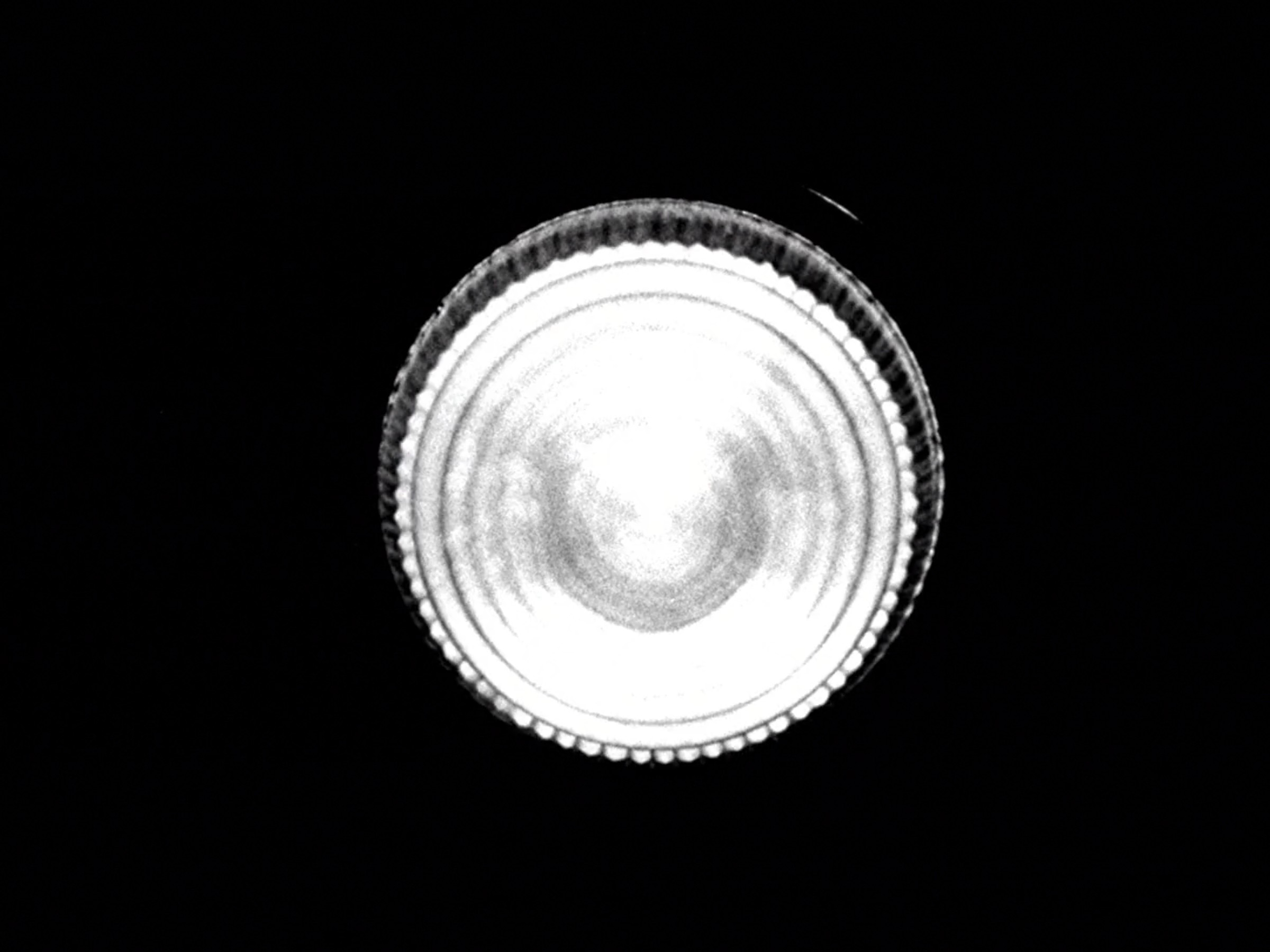

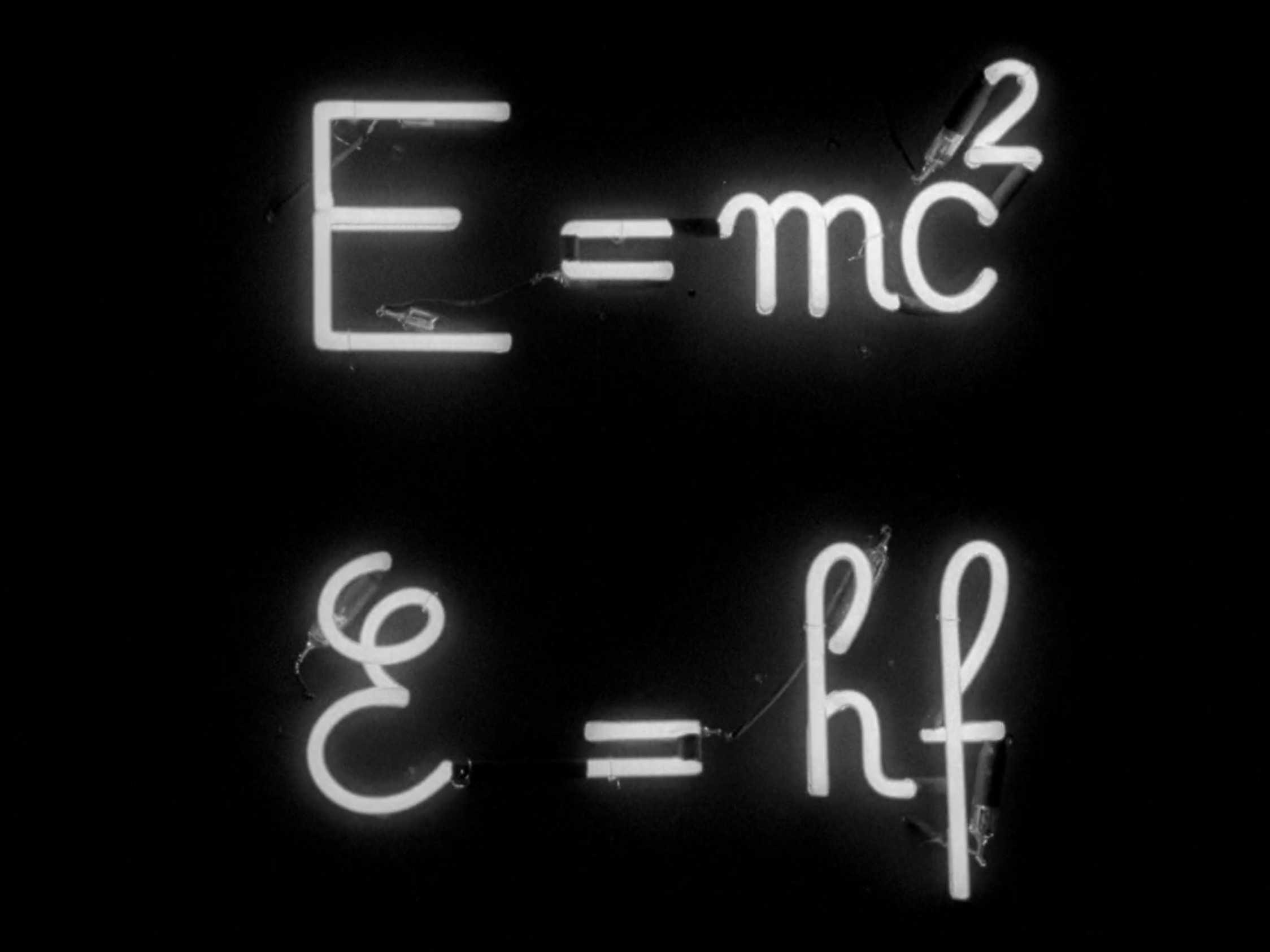

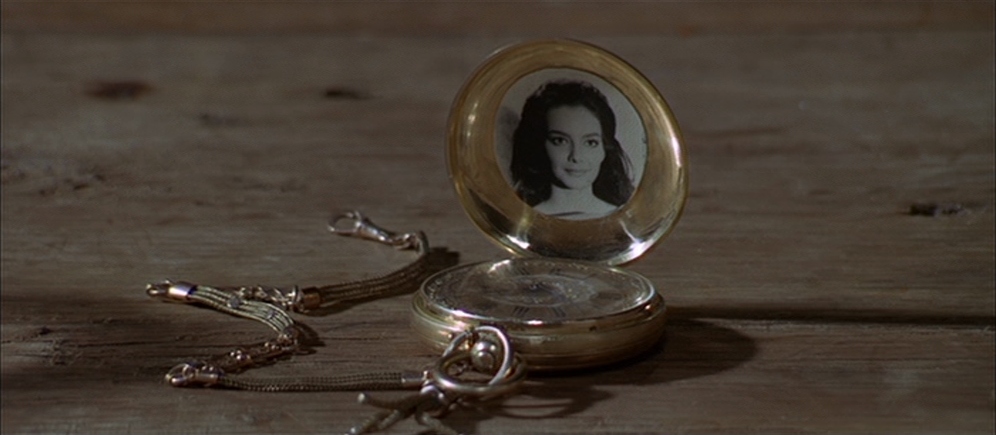

After all, the Colonel is not merely in this for the payout, as handsome as it is. His stakes are personal, and although we don’t learn the details until Leone’s climactic conclusion, the foundations of this grand reveal are woven throughout El Indio’s backstory. Most prominently, flashbacks to the time he raped a woman, murdered her family, and stole her musical pocket watch as a memento sit like a pit in his stomach, hinting at a shred of guilt. Whenever it is opened, memories of that tragedy return in its delicate, tinkling melody, effortlessly weaving a haunting sadness into Morricone’s otherwise majestic score of electric guitars, percussive chants, and piercing whistles. This is the melancholy which resides in all these characters, his motif reminds us, feeding the vengeful sorrow which has transformed the frontier into a battlefield of personal vendettas. On a more sadistic level, so too is it a cruel countdown that El Indio frequently uses in duels, challenging his opponents to only draw their pistols when its wind-up tune has run out.

This pocket watch thus makes for a fitting accompaniment to his and Mortimer’s eventual showdown, staged within the circular boundaries of a low stone wall. As its melody slows to a halt though, an identical tune suddenly starts up elsewhere, and Leone cuts to a magnificent wide shot of both men on either side of the frame with Manco’s hand in the centre. There, a second pocket watch he pilfered earlier from Mortimer is flipped open, and the historic connection between hero and villain comes to light. El Indio’s eyes move between the pocket watch’s photo of his victim and his adversary, and recognition of a family resemblance crosses his face – yet this is not his story to see through to its completion. For the first time in his life, he is the slowest to draw, and Mortimer chooses not to claim the monetary reward, but rather the inner peace he has long pursued.

With set pieces as awe-inspiring as these, it is virtually impossible to separate Leone’s cinematic style and mythic storytelling. Character emerges from action, which is in turn born from a flawless synthesis of staging, music, and editing, revitalising the Western genre with the countercultural vigour of the 1960s. Manco is not a classical hero serving righteous ideals for the betterment of society, but a killer who sees death as little more than a commodity to be traded, though at the very least there is some grace to be found in Mortimer’s consideration of murder as an act of moral justice – however bloody it may be. In the absence of men living by virtuous principles, For a Few Dollars More gives us gunslingers choosing to wield their darkness as weapons, and strengthened by the coalition they form against greater, far more rotten evils.

For a Few Dollars More is currently streaming on SBS On Demand, and is available to rent or buy on YouTube and Amazon Video.