Federico Fellini | 2hr 18min

Common wisdom says that 8 ½ is titled after the number of films Federico Fellini had directed at this point in his career, the total consisting of six previous features, two shorts, one co-directing effort, and this, his most autobiographical, self-reflexive piece of cinema yet. It would have been represented as an entirely different numeral had none of those fallen into place, but instead we get this incomplete fraction, stuck between integers as if waiting to be filled in.

The same could be said of the two Italian directors connected to this film, with both the fictional Guido and real-life Fellini reflecting on the pressures of fame, religion, art, and relationships tugging them in multiple directions without any unifying principle. Thanks to their professional careers, they are familiar with the unique suffering that comes with overactive imaginations trying to sort through fragmented lives of excess, but ironically this vocation is one of the few that seeks to deliver a catharsis for the issues it has created. Finding relief is not so simple as projecting one’s crippling insecurities up on large, flickering canvases, but rather arrives through humbling self-examination, opening one’s mind up to a world that may either praise the genius it sees or eviscerate it for a lack of inspiration.

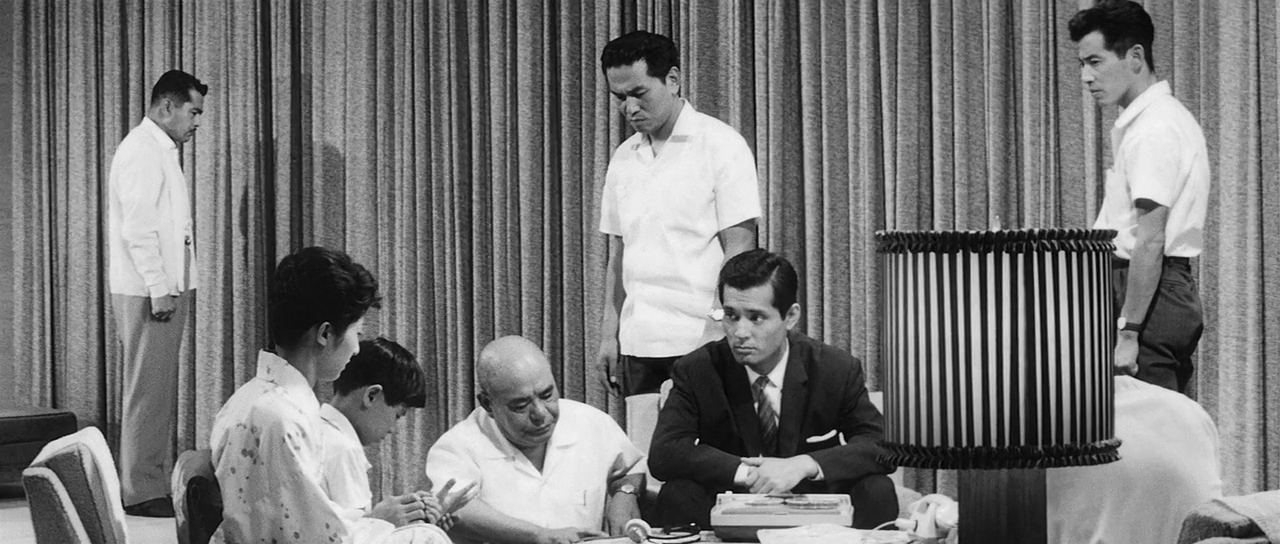

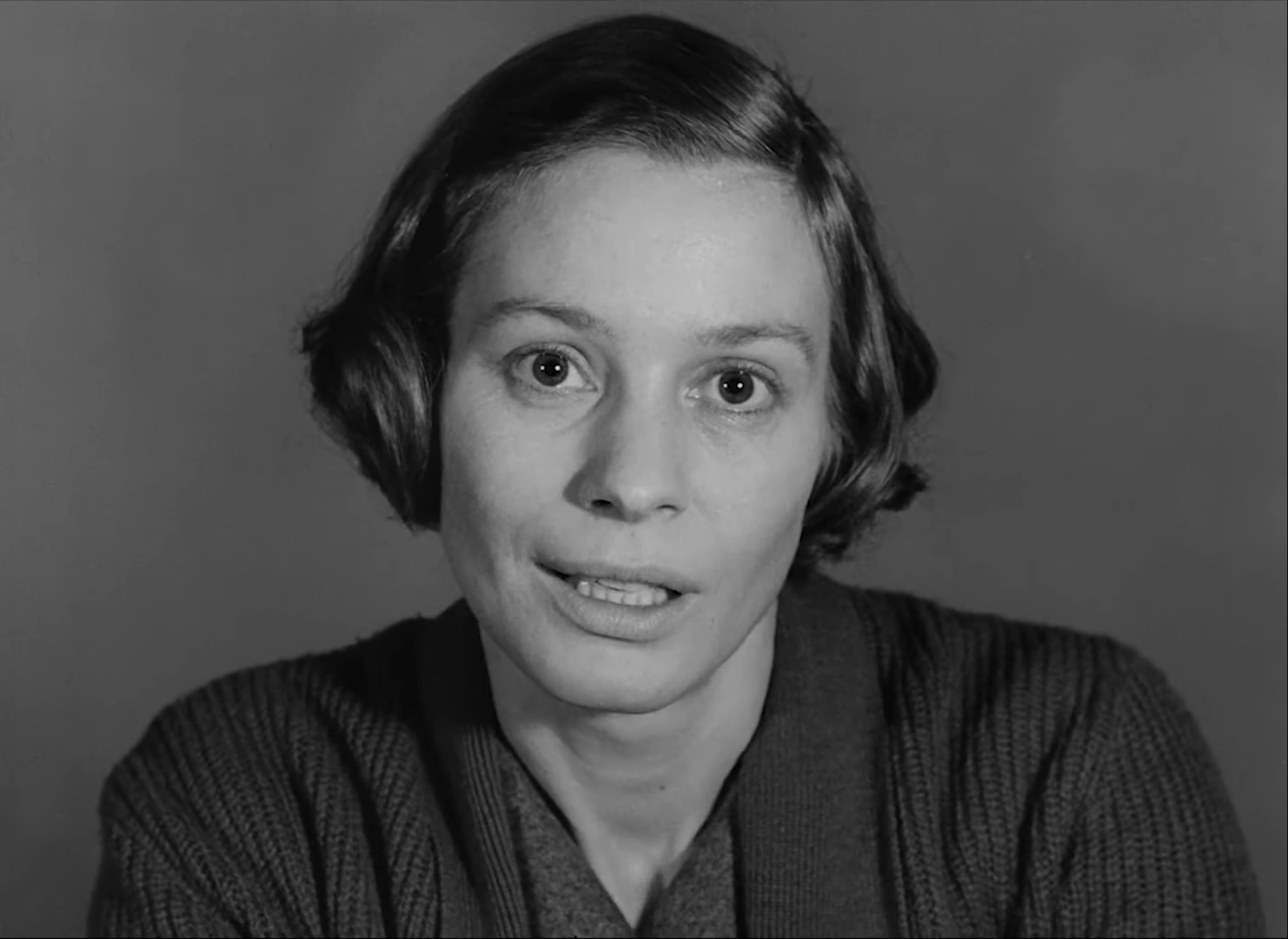

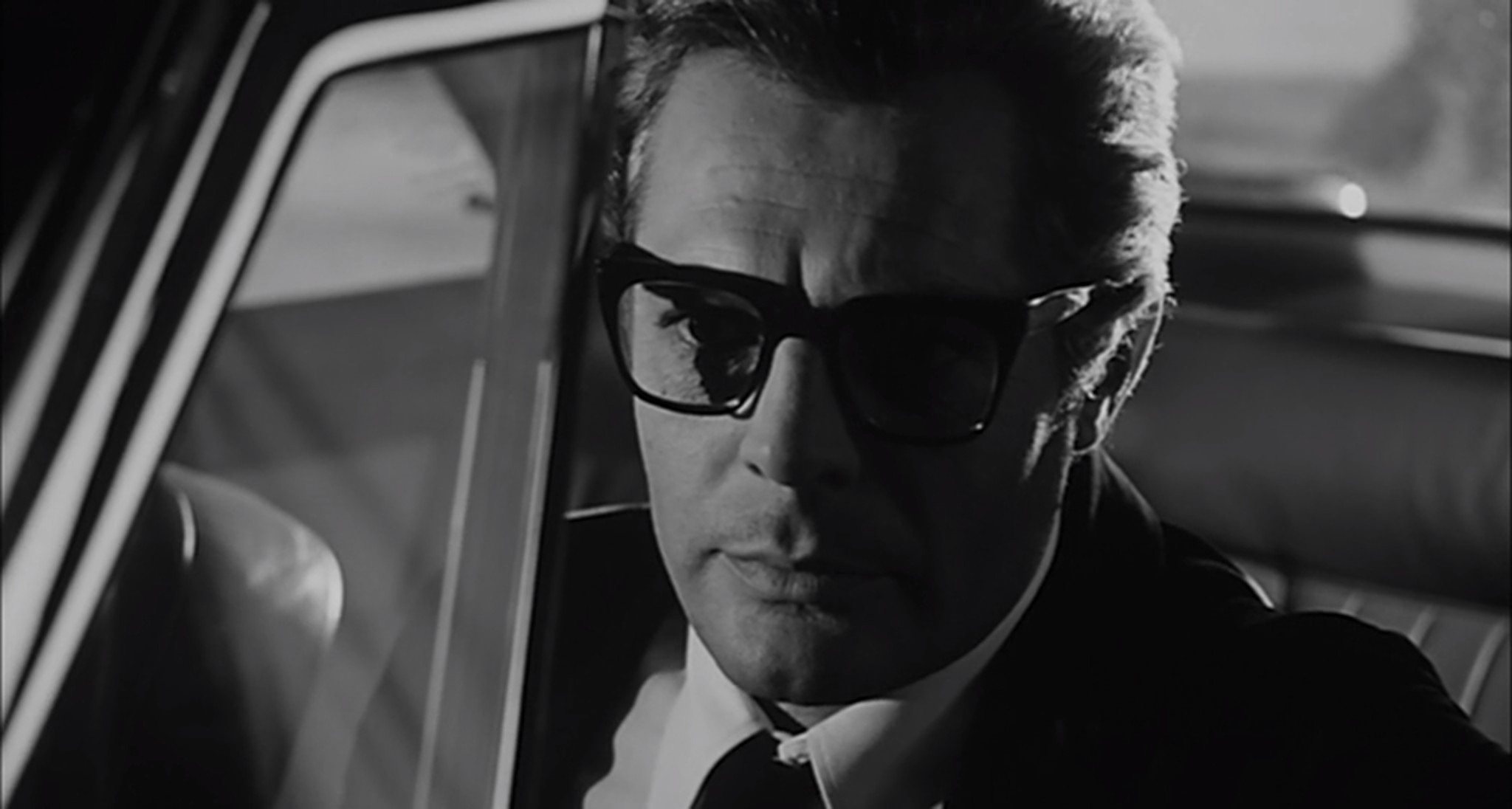

For Guido, there are few nightmares worse than this claustrophobic social anxiety. Caught in the middle of a traffic jam, he bangs on the windows of his car as if suffocating from the stagnation, while the silent witnesses of neighbouring vehicles passively watch his struggle with cold, bored expressions. Among them, bus passengers hang their arms outside windows, while an older man in a car seems more preoccupied with his glamorous female companion. Quite eerily, there are no engines to be heard on this busy stretch of road, and neither do we see any close-ups of Guido’s panicked face which might have otherwise oriented us in the scene. Even his escape and liberating ascent into the sky are eventually spoiled by a man looping a rope around his ankle, tethering him to the earth like a kite that can only soar so far before crashing back down. When he awakes, the surrealism dissipates, and yet Fellini still holds back from revealing the face of his surrogate as doctors and colleagues bring their consultations to his hotel room. It is not until he is able to get some time to himself in a bathroom that he is revealed in full, and that Marcello Mastroianni’s perturbed, restless performance finally starts to lift off.

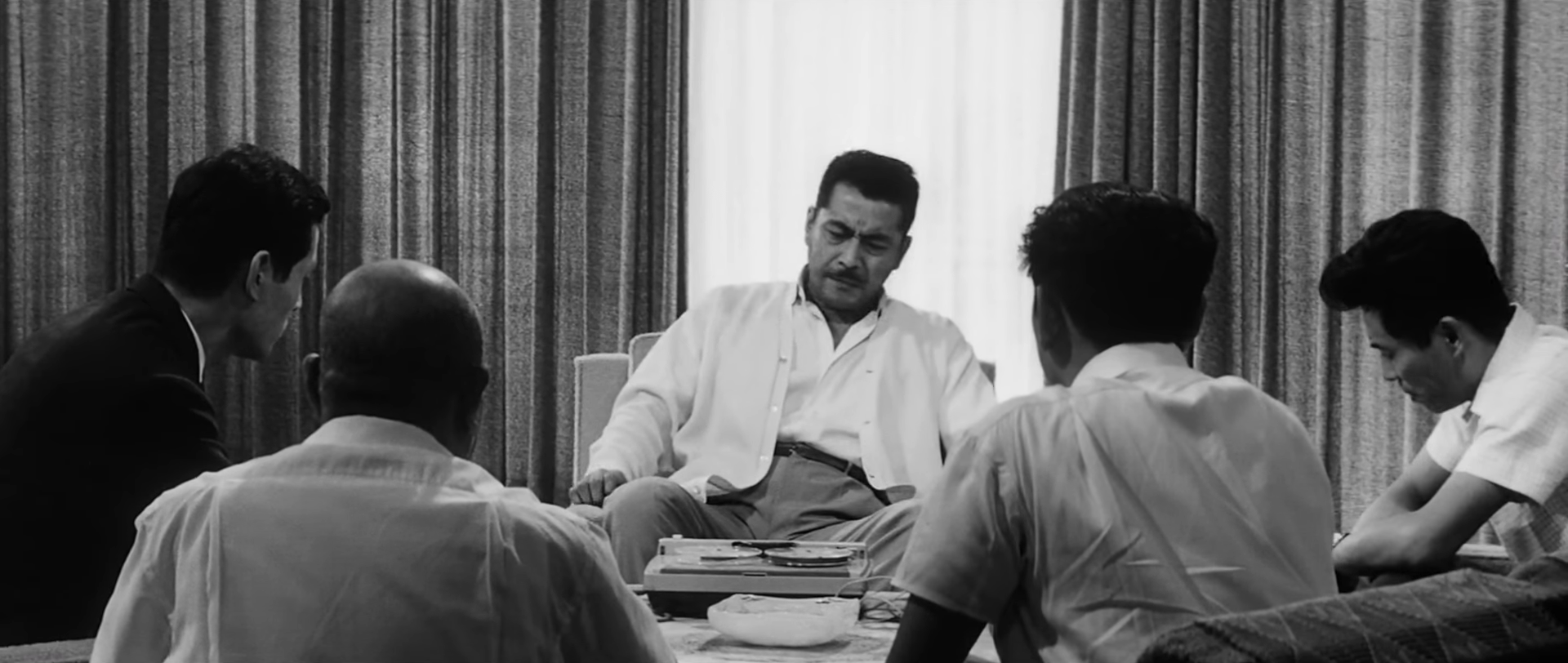

Even at the spa retreat where Guido hopes to compose himself before embarking on the production of his next film, there is little hope that he will find the peace that he desires. How ironic that even within this sanctuary of rejuvenation, he still finds no escape from journalists, casting directors, crew members, sycophants, agents, and fans turning up with questions ranging from the trivial to the overly invasive, none of which are particularly helpful in curing his director’s block. It is not an issue of funding or resourcing, but he is simply not mentally prepared to offer up anything of value to his audiences.

In Fellini’s own career, La Dolce Vita and 8 ½ mark the point where he begins to veer further away from his roots in neorealism, and so it is not difficult to imagine himself in Guido’s position facing a culture of excessive fame and materialism, trying to create something grounded in real world issues. The result is a psychological dive into his own self-critical mind, picking apart this exact struggle in lavishly designed sets that don’t even bother trying to conceal his own abundant wealth and privilege.

Out on the resort’s blanched white terrace, patrons gather beneath umbrellas and in lines for mineral water, though Fellini rarely hangs on wide shots long enough for us to adjust to the blinding environment. Apparently, reality is just as disorientating as Guido’s dreams. While strangers and associates gaze right down the lens in point-of-view shots, Fellini’s constantly panning camera couldn’t get away from them sooner, disengaging and drifting through the surroundings so that their lines of dialogue essentially become voiceovers. Every so often though, a new character’s face unexpectedly moves into the frame, manifesting like a phantom and suddenly readjusting long shots into close-ups. To throw us off even further, Fellini often has his actors direct their eyeline behind the camera as they speak to Guido, only to pull back and reveal him standing elsewhere in the scene.

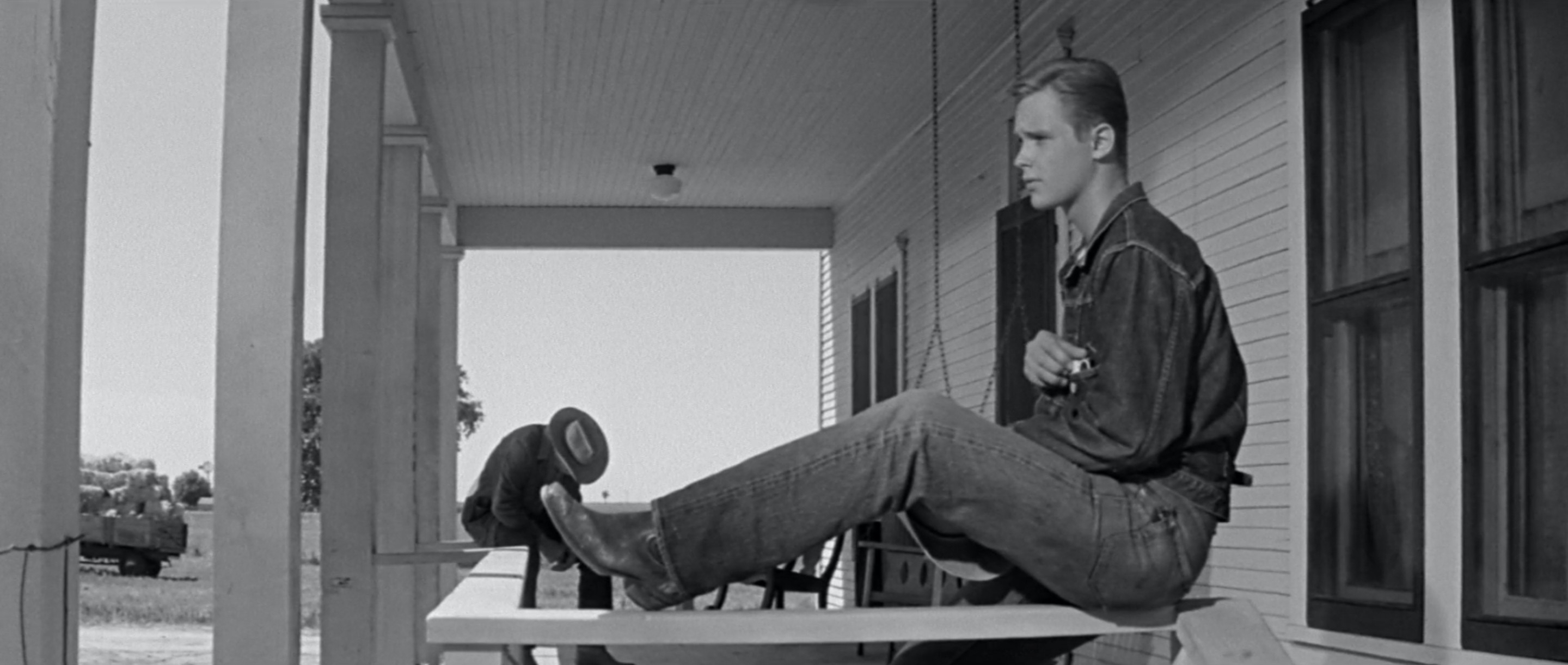

It certainly doesn’t help either that among his closest associates are embodiments of his deepest self-doubts, such as industry veteran Conocchia whose ideas are a little too stale for Guido’s taste, reminding him of his own encroaching irrelevance. Old friend Mario is also present at this retreat with his young fiancée Gloria, and their effortlessly cool dance scene here is one for the ages as they joyfully twist to the sound of modern jazz, unknowingly inspiring Pulp Fiction’s equally iconic dance some thirty years later. From the sidelines though, Guido can’t help but cast judgement upon what he perceives as a middle-aged man’s embarrassing grasp at youth – a fate which he realises similarly awaits him.

With pressure mounting on Guido from every side at this spa resort, Fellini keeps up a persistent anxiety in his jarring visual whiplash and frenetic classical musical cues drawn directly from the works of Wagner and other classical composers. As he snaps us between characters, priorities, and dreams that can’t quite congeal into anything productive, ‘Ride of the Valkyries’ imposes an overwhelming intensity upon Guido’s social obligations, while his subsequent humming of this tune suggests that this grandeur exists solely in his own head. Later when he is confronted by the reprovals of a film critic, it is Rossini’s ‘Overture’ from The Barber of Seville that heightens his anxiety, underscoring his greatest creative insecurities as they are brought to light.

“On first reading, it’s evident that the film lacks a central conflict, a philosophical premise if you will… making the film a series of gratuitous episodes, perhaps even amusing due to their ambiguous realism. One wonders what the author’s point is. To make us think? To scare us? From the start, the action reveals an impoverished poetic inspiration. Forgive me, but this might be the most pathetic demonstration ever that cinema is irremediably behind all other arts by fifty years. The subject matter doesn’t even have the merits of an avant-garde film, while possessed of all its shortcomings.”

The hints of this criticism being directed towards 8 ½ itself isn’t easily missed. If art reflects one’s mind, then this director’s block necessarily calls Guido’s value as a filmmaker into question. Disappearing into his own fantasies might at times feel like the single most effective way he can run from these feelings, as demonstrated in one dream where a harem of women falls at his feet and offer him a power over those in his life he feels threatened by. Still, an unfiltered, self-critical imagination can be an unwieldy thing. Just as it is an endless source of creativity, so too can it spiral off in egotistic directions or turn against the dreamer themselves, as these women do when they catch onto Guido’s misogynistic hypocrisy.

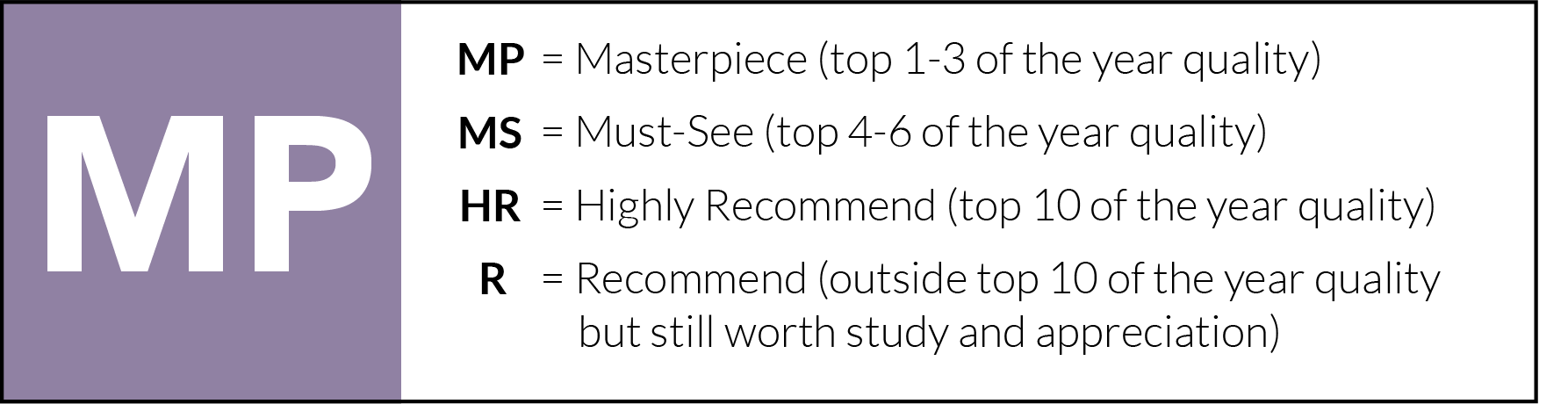

Another layer of Guido’s psyche offers portals into his past, though rarely are they so straightforward as to be direct representations, clouded by discontinuity in Fellini’s editing and constantly shifting camera perspectives. When a magician reads his mind at the resort, the apparently meaningless words “Asa nisi masa” seemingly come from nowhere, yet are shortly revealed through flashback to be a mystical phrase taught to him by his peers at a Catholic boarding school. These formative years are at the core of his being today in many ways, especially seeing how his pampering by school staff is mirrored in his present-day harem fantasy, fetishising a worshipful, almost maternal treatment from female lovers.

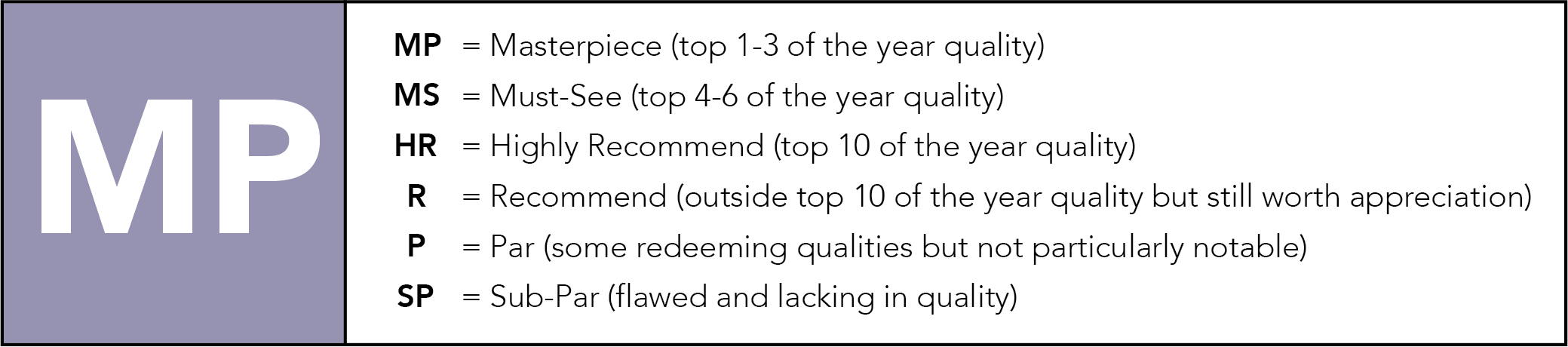

This Freudian angst is complicated even further in 8 ½ with Guido’s frequent hallucinations of his deceased parents. In his mind they are slippery, malleable figures, with dreams of his mother transforming into his wife Luisa with a sly cut, and weeping over his sexual vices after he makes love to his paramour. His shame seems to be tied to his sexual development as an adolescent too, when he and his schoolmates paid La Saraghina, a prostitute who lived in a shack down at the local beach, to dance for them. The Catholic guilt beaten into him by the school priests after being caught out for this is instrumental in shaping his constant search for religious approval, as in the modern day he is still trying to appease a Monsignor imposing a strict Christian morality upon his film. Despite his aspirations to prove his spiritual wholeness though, visions of La Saraghina frequently intrude at the most unexpected times, denying him any escape from his mortifying past.

Even above Guido’s desire to create art is his need to be loved and affirmed, not just by a select few, but by everyone – the religious, the secular, the fans looking for entertainment, the critics looking for intellectualism, his many love interests, and even his deceased parents, who continue withholding their affection in death. Hope seems lost after Luisa witnesses his bitter, cinematic representation of their marriage and leaves him, and the arrival of a beautiful actress who he believes is perfect for a role impossibly described as “young and ancient, a child yet already a woman” does little to assuage his insecurities. Even while he venerates her as an idealised, abstract concept, she cuts him down, recognising the character he has based on himself as being incapable of love.

Pleasing just a single person seems to be an impossible task, let alone the hundreds of people begging for answers, and therein lies the source of Guido’s creative block. “Everything happens in my film. I’m going to put everything in,” he proclaims, but in catering to the desires of so many others, there is nothing truly authentic or honest about his artistic expression. In his impossible endeavour, he has become a walking paradox: a director with no direction, the observer becoming the observed.

“I wanted to make an honest film. No lies whatsoever. I thought I had something so simple to say. Something useful to everybody. A film to help bury forever all the dead things we carry around inside. Instead, it’s me who lacks the courage to bury anything at all. Now I’m utterly confused, with this tower on my hands. I wonder how things turned out this way. Where did I lose my way? I really have nothing to say… but I want to say it anyway.”

Finally, the day of shooting arrives for Guido, and he has to practically be dragged on set against his will. Once again, the crowds of journalists, critics, and crew are present, blasting him with questions of political, tabloid, and spiritual natures. “Can you admit you have nothing to say?” one man cruelly jabs, as Fellini’s frenetic editing and score keeps trying to build to a climax. “Just say anything,” he is advised, but still, there is nothing that comes from his mouth. Within the crowd, Luisa is present in her wedding dress, taunting him with memories of happier days as he too wonders where they went. And of course, casting a shadow over the chaotic press conference is his giant launchpad set – a hulking steel monument to his own meaningless ambition and grounded imagination, offering empty promises of space-bound adventures with the clear absence of a rocket

Beneath its menacing shadow, the only feasible solution to all Guido’s troubles seems to be a clean, sharp gunshot to the head, though not before a guilt-inducing vision of his mother asks where he is running to. At first this suicide seems to be nothing but another dramatic diversion from reality, adding one more drop to the sea of memory and dreams that Fellini traverses with such elusive grace, and which keeps obscuring the boundaries between Guido’s inner and outer lives. Symbolically though, it is a perfect merging of the two. What Fellini purposefully avoids depicting here is the explicit reveal that he has aborted production on the film, and only showing the aftermath of this decision when we return to reality. In killing his failed project, he has successfully killed the part of himself that simultaneously strives to live to impossible expectations and scorns the people setting those standards.

It is perfectly fitting to 8 ½’s cinematic form that Guido’s monologue announcing his fresh perspective is not the focus of these final minutes, but instead simply underscores a grand, visual sequence that could only ever be rendered through this artistic medium. Not even the critic’s disparaging words can kill the rising joy he feels in this moment, as Fellini cuts through a montage of all those people who make up Guido’s identity smiling right at the camera, and congregating for the first time in a single location. “How right it is to accept you, to love you. And how simple,” he ponders, as men in tuxedos shout to crew members standing up on lighting rigs, who aim their beams towards the rocket launchpad.

“Life is a party, let’s live it together. I can’t say anything else, to you or others. Take me as I am, if you can. It’s the only way we can try to find each other.”

Though Guido’s lips are not moving with his voiceover here, Luisa can hear him perfectly. Between the two estranged spouses, finally there seems to be some sincere attempt at understanding. Only in shaking off his constant need for approval is he able to connect with others in any meaningful way, receiving them as they are, and in turn presenting his most honest self to the world without shame.

Not far away from the site of this epiphany, a small, ragtag marching band of carnival performers parade towards the set’s scaffolding, and a set of makeshift white curtains are suddenly pulled back. Behind them, every single character we have met throughout 8 ½ comes pouring down the steps of this magnificent launch pad as if attending some grand parade conducted by Guido, who directs them into a single, unifying fantasy. Far removed from the frivolous, empty spectacles of La Dolce Vita, the circus of 8 ½ becomes a celebration of communal delight, piecing together the fragments of the director’s life in a giant circle and spinning them hand-in-hand around the set. For any artist seeking a practical execution of their avant-garde ambitions, creativity and creation are not always perfectly synchronised. In painstakingly lining these up through Fellini’s wildly surreal stylings though, 8 ½ stands as history’s most brilliantly compelling piece of self-reflexive cinema, seeking to examine the arduous processes of its own construction.

8 1/2 is currently streaming on The Criterion Channel, and is available to rent or buy on iTunes and YouTube.