Louis Malle | 1hr 31min

After assassinating his boss, staging the scene to look like a suicide, and stealthily exiting the office building after hours to run away with his victim’s wife, all it takes is a single loose end to trip Julien up. The rope he used to scale the wall still hangs from the balcony, and the only way to retrieve it is to get back up, remove the evidence, and take the elevator down before making his getaway. No one will be in until Monday morning though, so surely all of this shouldn’t be too much of a setback?

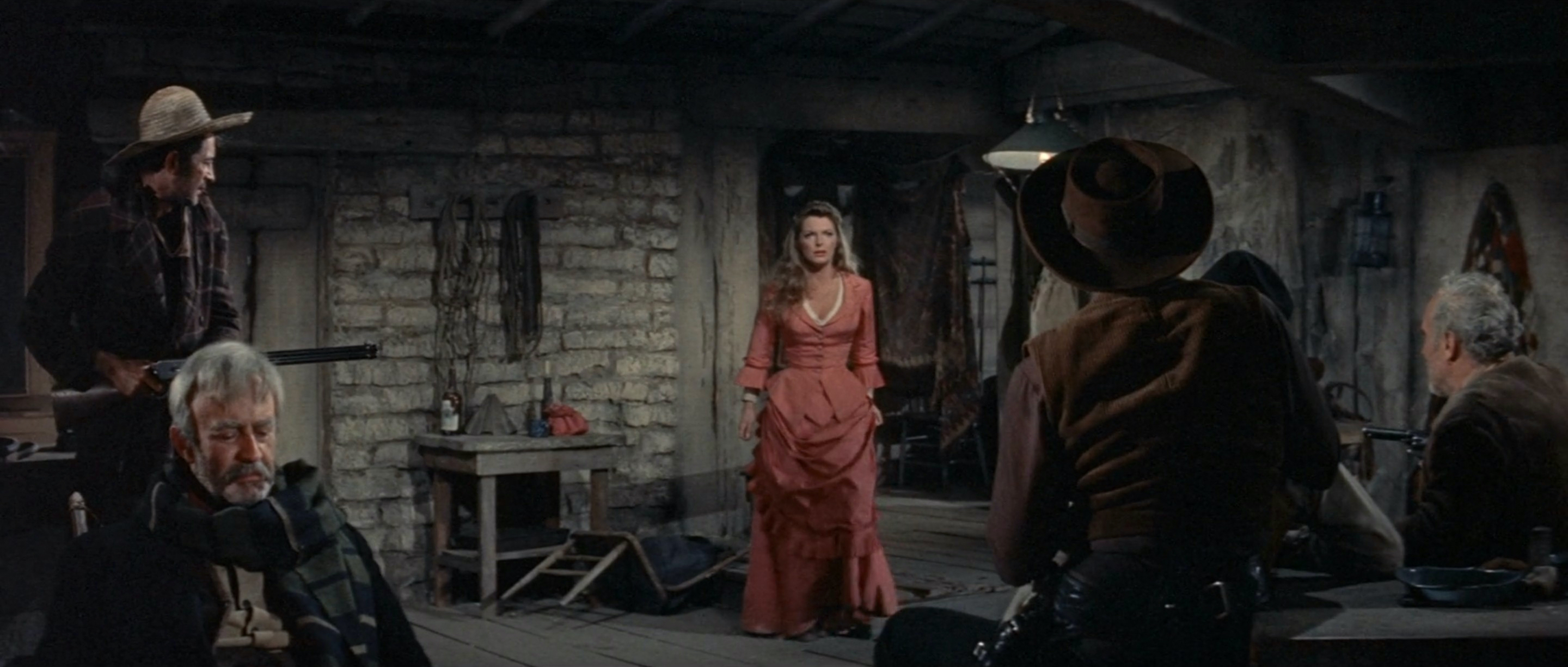

Unfortunately for Julien, the fatalistic pull of destiny has other intentions in Elevator to the Gallows, playing malicious games that intertwine his tale of love and crime with a younger, more reckless couple. Louis and Véronique are a Bonnie and Clyde for 1950s Paris, but not nearly as clever in their spontaneous rebellions. Just as security turns off the building’s power and unknowingly traps Julien in the elevator for the night, these foolhardy lovers impulsively decide to steal his car, possessions, and identity, found tucked away in his wallet. After a friendly German couple they have been drinking with call out their fraudulence, Louis is similarly driven to homicide, though it is fortunately not his name that was written on the motel registration. As a result, a manhunt begins for one Mr. Julien Tavernier – just not for the crime he has actually committed.

With such sophisticated formal patterns knitting together these parallel plotlines in Louis Malle’s narrative, it isn’t a stretch to imagine a more comical version of this film that possesses the dry, morbid humour of the Coen Brothers, contemptuously observing amateurs botch and cover up murders. As an off shoot from Classical Hollywood’s film noir and a precursor to the French New Wave though, Elevator to the Gallows is as deadly serious as can be, prioritising a dark, seductive atmosphere over intricate plot machinations. The melancholic score warrants priority in such an analysis, typifying the jazzy musical style that many falsely associate with American noirs, even though the inspired innovation first occurred here with Miles Davis improvising trumpet lines over a steady accompaniment of piano, saxophone, double bass, and drums. Never has there been a greater sound to match Jeanne Moreau’s dour, brooding expression than this, reverberating a sombre loneliness as she saunters past streetlamps dimly illuminating her rain-drenched face, before sinking her back into the shadows of Paris’ wet, gloomy streets.

As Julien’s lover Florence, Moreau is merely one player in Malle’s ensemble, but every scene she shares with a co-star inevitably sees her intoxicating presence dominate the screen. After working in the film industry for almost a decade, Elevator to the Gallows marked her true breakout, and would propel her on to fruitful collaborations with other French directors including François Truffaut, Jean-Luc Godard, and Jacques Demy. Her introduction here through extreme close-ups and hushed whispers over a telephone line is treacherously intimate, inviting us into a shady urban world our gut is telling us to steer clear of, yet which nonetheless piques our curiosity. Despite her direct implication in her husband’s murder, our heart still breaks when she is led to believe she has been betrayed, while Malle’s breathtaking location shooting sets her morose depression against bleary backdrops of Paris’ lights and vehicles.

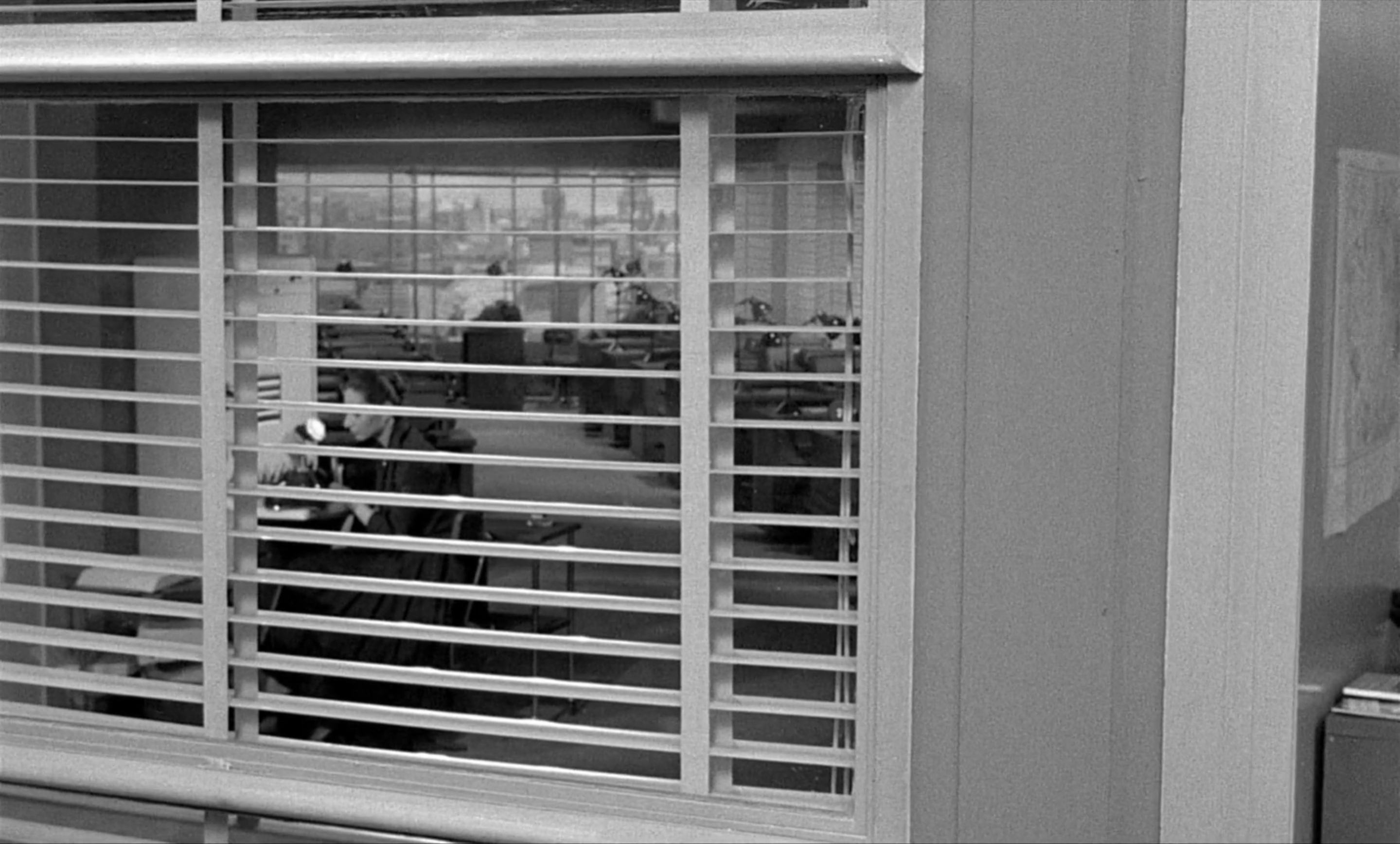

Alongside Malle, credit must also go to the expressionist photography of Henri Decaë as well, who in 1958 was already on a trajectory towards greatness through his collaborations with Jean-Pierre Melville. The Venetian blinds, chiaroscuro lighting, and skilfully blocked compositions are evidently signs of two visual artists well-acquainted with film noir conventions, and how they can be manipulated to breed suspense. At the same time, the lack of studio polish in Elevator to the Gallows also signals a purposeful engagement with cinema’s avant-garde potential. Malle is clearly looking to its future here just as much as he is calling back to its past, and isn’t afraid to let his narrative wander off on tangents that we trust will eventually tie back together, paying off on the intriguing formal mirroring between these couples.

By the time Julien manages to free himself from the elevator the next morning, his picture has already been posted in local papers for the crime committed by Louis and Véronique, who in turn have attempted suicide back home to avoid capture. Time passes slowly in the black void where Julien is captured and interrogated in a black void, drifting by on long dissolves while Florence works desperately on the outside to absolve him of his false accusation. Just as Julien’s rope had ruined an otherwise flawless murder and cover-up, so too are Louis and Véronique incriminated as the German couple’s killers by the roll of film they had stolen from Julien’s car, and carelessly left behind at the motel. Unfortunately for Florence though, so too does it contain photos revealing the truth of her affair with Julien, and thereby expose them as her husband’s executioners.

Not only that, but Florence’s own future seems far rockier now that she has been implicated too, while the death sentence that Julien was previously facing seems to be downgraded to a few years in prison. As Davis’ wistful trumpet croons, Malle’s camera sits on those photos of Florence and Julien slowly developing in the rippling water, just barely catching the upside-down reflection of her sombre face. “No more ageing, no more days. I’ll go to sleep. I’ll wake up alone,” her voiceover murmurs, resigning to a destiny she still hopes will one day set her free.

“Ten years, twenty years. I wasn’t indulgent. But I know I still loved you. I wasn’t thinking of myself. I’ll be old from now on. But we’re together here. Together again, somewhere. You see, they can’t keep us apart.”

If fate can find its way back to the perpetrators of two near-perfect crimes by unexpectedly converging both, then surely it can also one day reunite these sweethearts whose love must be similarly preordained, Florence reasons. Given how much destiny seems to have a mind of its own throughout Elevator to the Gallows though, it is not so easy for us to rely on the faith of a condemned, lovesick woman, desperate to find hope in a perilously mischievous universe.

Elevator to the Gallows is currently streaming on The Criterion Channel, and the Blu-ray is available to purchase from Amazon.