Federico Fellini | 1hr 52min

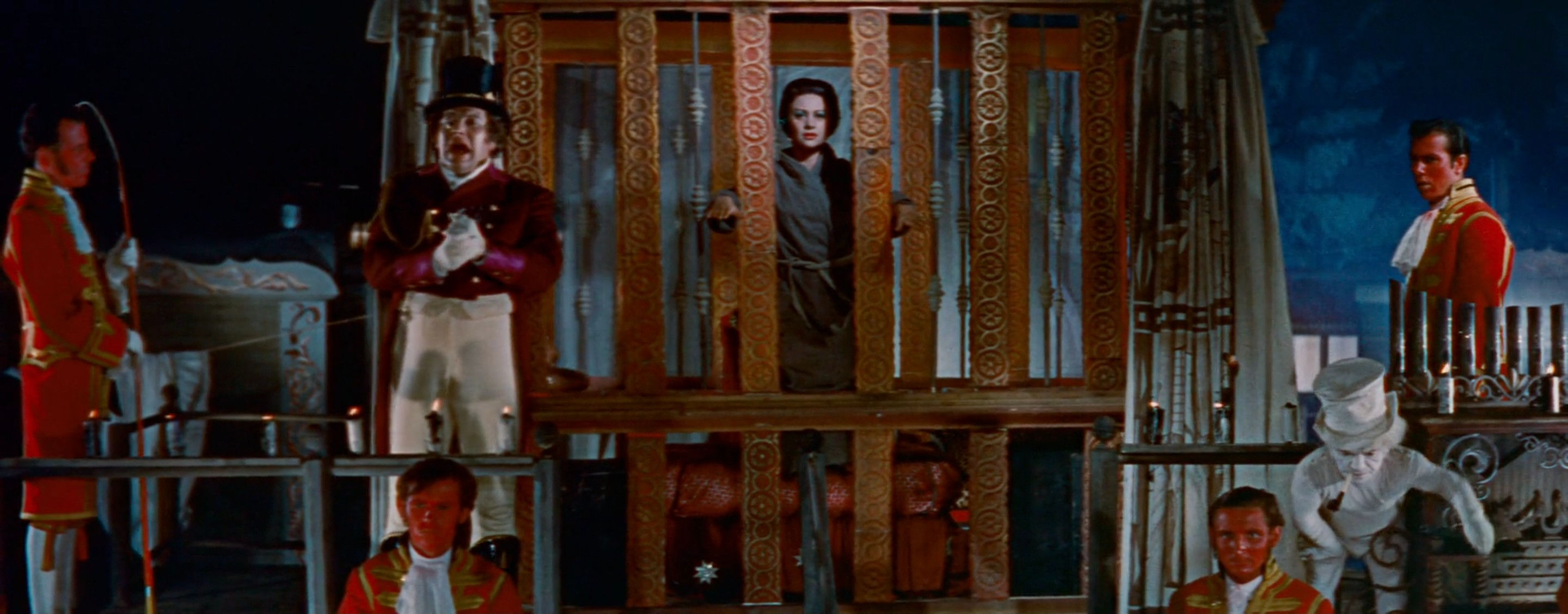

So desperate is the working class of Il Bidone’s post-war Italy, it seems that they are ready to believe any stranger who comes bearing dubious promises of financial stability. Perhaps with some retrospect, they might realise how strange it is that government bureaucrats would promise public housing to anyone in a crowd who comes forward with a deposit. Even more ludicrous a scenario is Vatican clergymen visiting a farmer’s property, bearing papal orders to dig up their land and uncover a repentant criminal’s bones, treasure, and will that stipulates the landowner must pay the church before receiving any money. Those who carry an air of confident authority can easily gain the trust of the needy, and naturally as the oldest and most experienced of his crooked crew, that is exactly Augusto’s greatest strength.

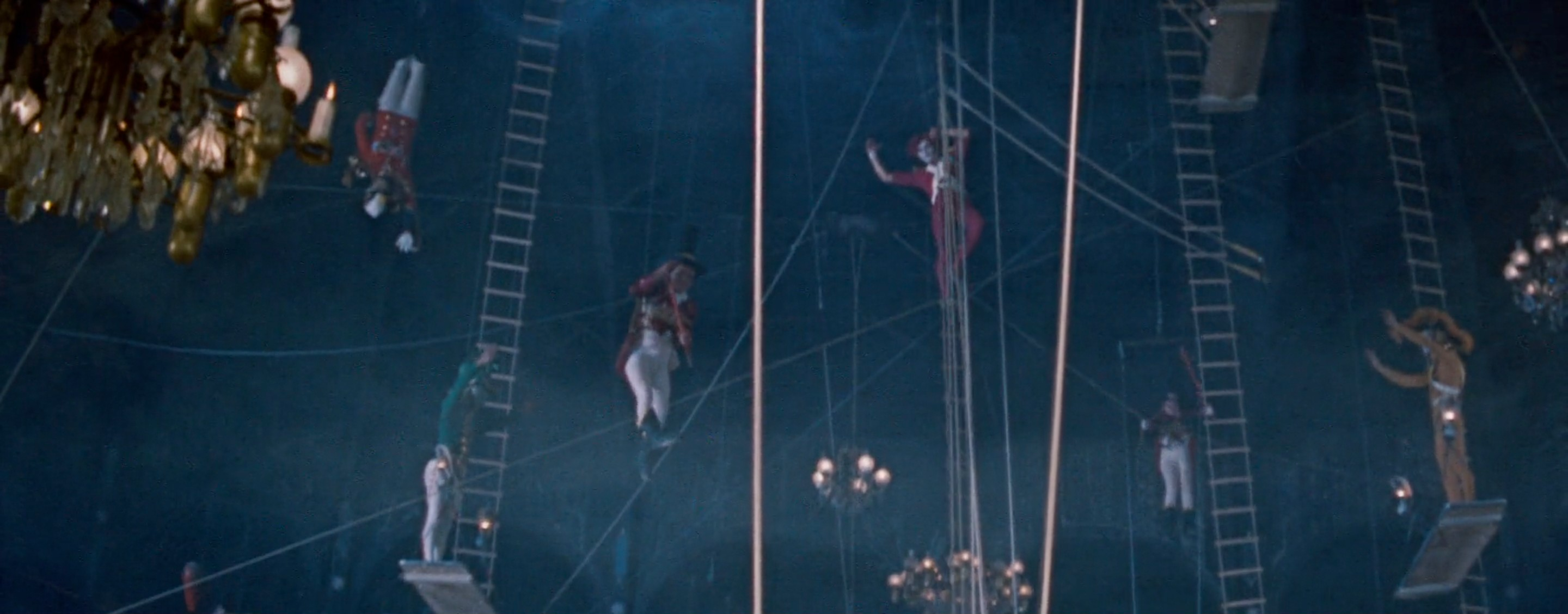

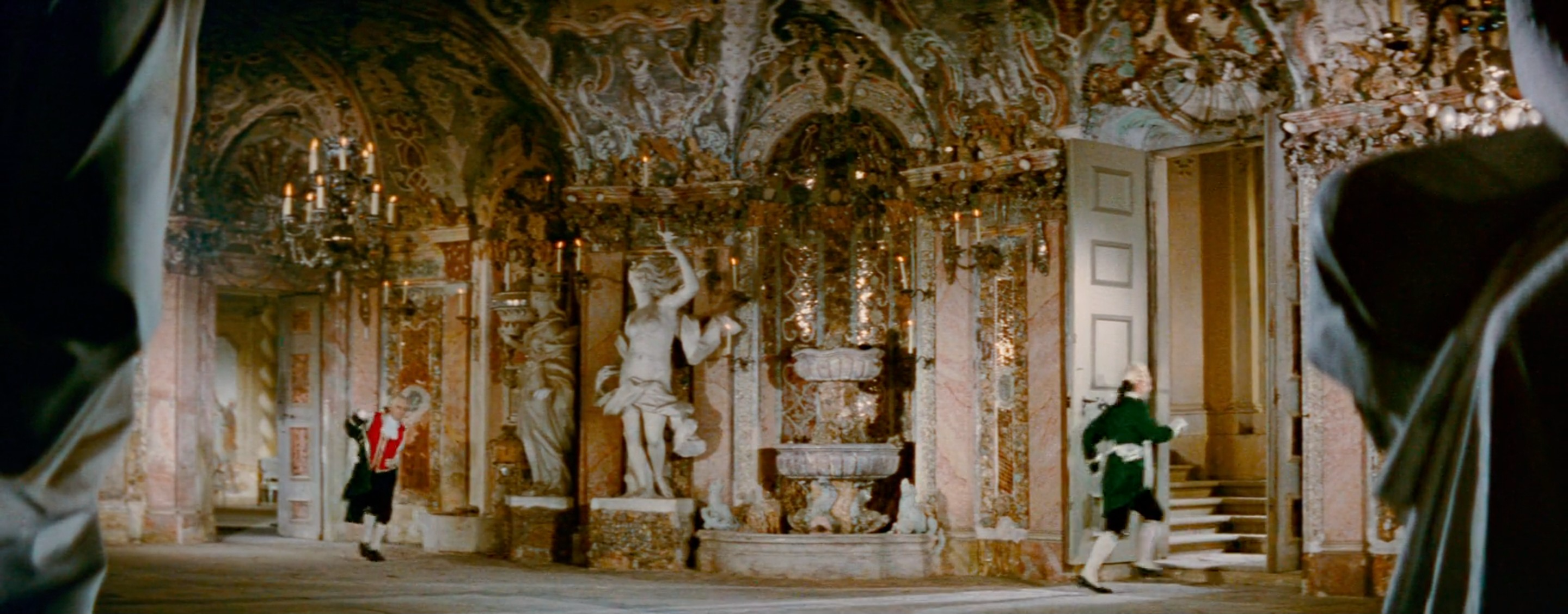

True to Federico Fellini’s contemplations of morality and corruption in modern Italy, Il Bidone is deeply engaged with lives of parasitic cruelty and the weight they bear on one’s conscience. Religion is effectively reduced to empty icons in their hands, stripped of the virtue it preaches and irreverently wielded as a means to an end. There may not be any of Fellini’s usual carnivals or entertainers present here, but Il Bidone’s conmen are nevertheless performers who profit off their carefully constructed spectacles. Much like their show business counterparts, total commitment is required from any swindler who wishes to succeed in his craft, and Augusto leaves no room for confusion regarding what sacrifices must be made.

“People like us can’t have families. One must be free to move. You can’t have a wife. You must be alone. The most important thing when you’re young is freedom. It’s more important than the air you breathe.”

Not that the companionship that these men find with each other instead is terribly fulfilling. At night they excessively indulge in luxuries purchased with their stolen money, drinking and dancing their guilt away. If there is any hope of escaping this cesspool of debauchery, then it comes in the form of family members longing for their husbands and fathers to be truly present, though such clean redemption is no easy objective. Just as the friends in I Vitelloni are awed by their leader’s overconfidence, the naïve Picasso here sees his associate Roberto as a model of masculinity, and ultimately finds himself torn between his charismatic lure and his wife’s desperate pleas to leave this unethical life behind.

Perhaps the most compelling relationship of Il Bidone though arrives through Augusto’s chance run-in with his estranged daughter Patrizia, just as he is on his way to another con. The humanity that had previously escaped his characterisation begins to manifest here with delicate caution as he attempts to rekindle this connection, offering to pay for her studies and bestowing gifts that she doesn’t realise have been stolen. It is a real tragedy that he is recognised as a conman during their outing together at a cinema – not so much for the judicial slap on the wrist, but rather for his humiliating exposure in front of the only person who still holds him in some esteem. The dramatic irony that stations Patrizia in the foreground watching the movie and Augusto’s confrontation in the background is made all the more discomforting by the crowd’s eyes slowly turning towards the commotion in a ripple effect, suspensefully edging closer to his oblivious daughter.

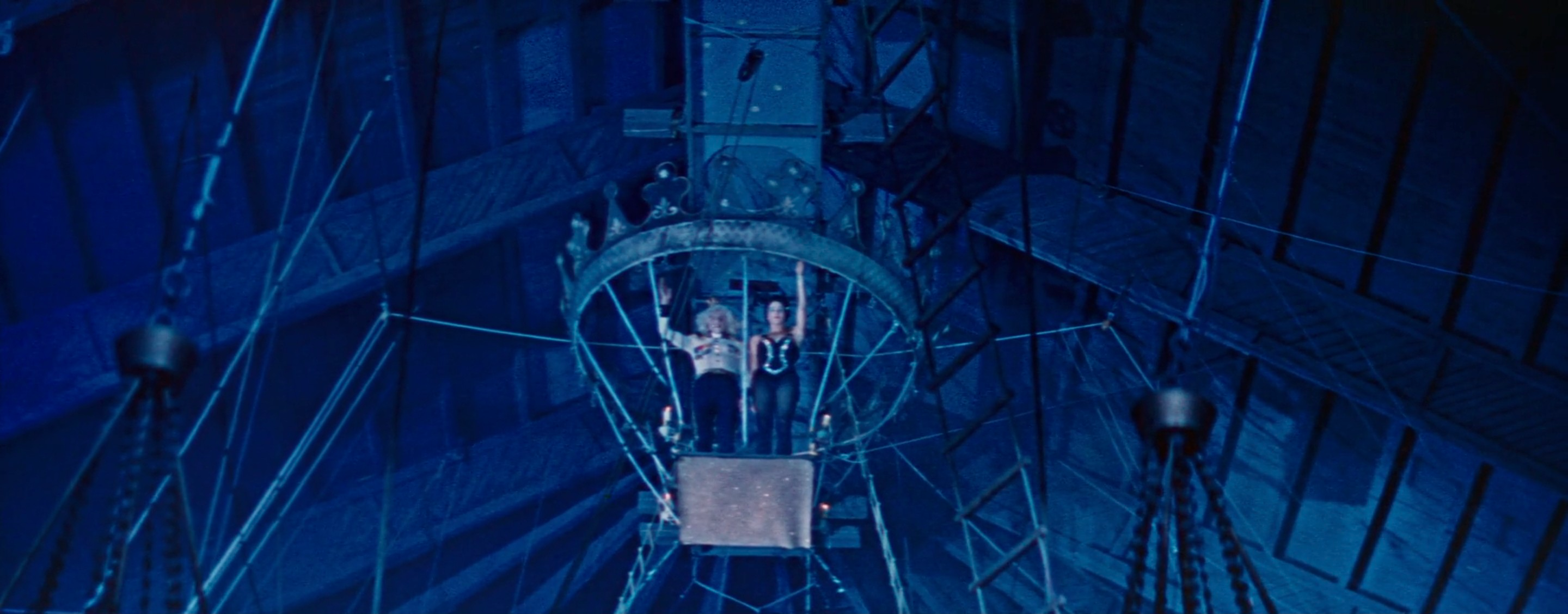

Even if Il Bidone is a step below his prior masterpieces I Vitelloni and La Strada, Fellini’s visual storytelling and blocking still land with bold dramatic impact in moments like these. His neorealist tendency towards shooting real locations with deep focus lenses constantly keeps the struggling communities being hurt by Augusto’s gang in view, and at the very least turns rough-hewn stonework and dusty rural farms into bleak backdrops. As long as the conman can keep an emotional distance from his targets, then he can continue exploiting them with little mind for their future wellbeing, and yet soon we begin to realise that his daughter’s broken belief in him has fundamentally altered his worldview.

By laying small reckonings of morality like these all throughout Il Bidone, Fellini earns the final step in Augusto’s redemption arc, formally returning to the religious scam which he conducted so effortlessly in the film’s first scene. When realising his victim’s daughter is a polio-afflicted teenage girl with a pure faith in God, his conscience can no longer bear the weight of his guilt. Torment and shame uneasily mount in Broderick Crawford’s flustered performance, though it is only when he makes away with his crew that they ultimately manifest as a bald-faced lie – he did not end up taking the money, he claims, but instead returned it.

It is at this point that we witness a religious icon be imbued with real meaning for the very first time in Il Bidone, rather than become a weapon of exploitation. As Augusto is robbed by his associates, beaten, and left on a hill to die, Fellini symbolically alludes to Christ’s sacrifice, bearing the sins of the world on the cross. Augusto’s honourable attempt to keep the stolen money from falling into criminal hands may be in vain, yet through physical and spiritual suffering, his soul is liberated. Rocky is the path to salvation in Fellini’s cinematic parable, but so too is it purifying, stripping back the lies and depravity of a modern world to uncover the grace that lies dormant in even the most dishonest man.

Il Bidone is currently streaming on The Criterion Channel, and is available to purchase on DVD or Blu-ray on Amazon.