Fritz Lang | Part 1 (2hr 30min), Part 2 (2hr 11min)

As a new medium of storytelling emerged in the early 20th century, the appeal in reimagining those archetypal fables of centuries past grew with it, paying homage to heroes and monsters who passed through songs, plays, and novels. The 13th century epic poem Nibelungenlied was very familiar with such adaptations too, building an enduring legacy through Richard Wagner’s operatic cycle ‘Der Ring des Nibelungen’, though it took a visionary such as Fritz Lang to recognise its extraordinary potential as a work of cinema. The result is a five-hour fantasy saga of ambition so grand, it is surprising that it often gets buried beneath his better-known films Metropolis and M. Nevertheless, Lang’s majestic tale of greed, betrayal, and vengeance stands as a monumental achievement of silent filmmaking, lifting mythical kings and battles out of legend and giving them extraordinary, larger-than-life form on the silver screen.

The impact of Lang’s creation did not fade with the passing decades and shifting cinematic trends either. Eighty years later, Peter Jackson would adapt the works of another storyteller deeply inspired by Germanic and Norse mythology – J.R.R. Tolkien, whose The Lord of the Rings series bear more than a passing resemblance to Richard Wagner’s cycle of operas, Der Ring des Nibelungen. Just as dwarven riches, fearsome dragons, and magic treasures are scattered through Siegfried’s quest for glory in the ancient legend, so too do Bilbo and Frodo Baggins encounter them in their own respective journeys, with archetypes reflecting humanity’s capacity for good and evil being deeply embedded in both.

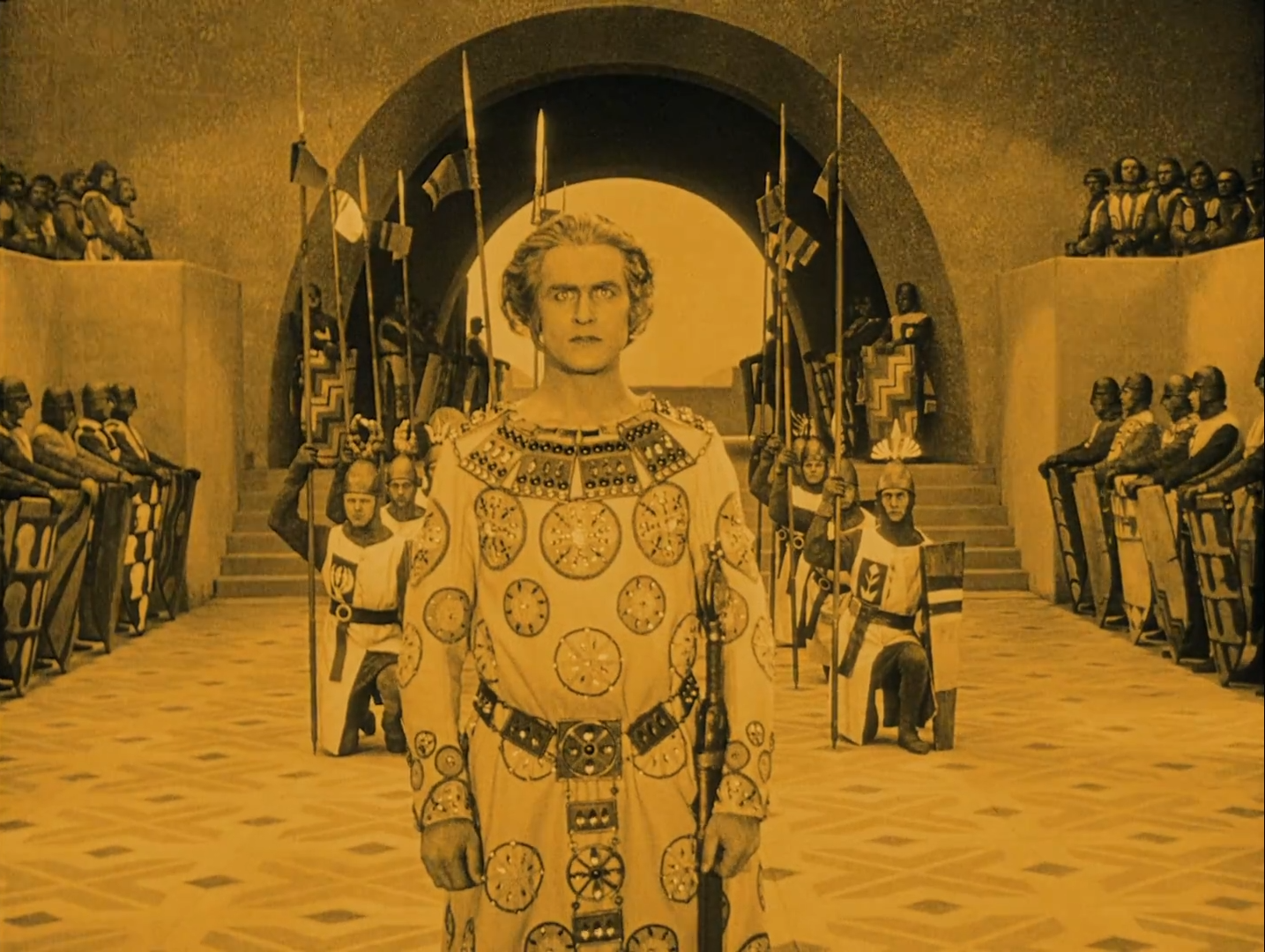

When Jackson eventually decided to take the reins and adapt The Lord of the Rings himself, we continue to see how his visual designs and staging drew influence from Lang’s own duology. The primitive mountain men who feast on hunks of meat look to be the prototypes of orcs, particularly with their unkempt makeup and hairstyling, while the imposing sets which comprise the Kingdom of Burgundy mirror the cavernous halls and fortresses of Middle Earth’s majestic cities. When Siegfried ventures to Iceland, Lang even uses magnificent castle miniatures upon steep mountains to personify Queen Brunhilde’s prideful, stubbornly independent character, laying the groundwork for similar architectural achievements three years later in Metropolis. Like Éowyn, she defies traditional gender roles as a powerful warrior, and yet the role she plays in ensuring Siegfried’s downfall alongside King Gunther’s devious adviser Hagen of Tronje reveals both to be cunning, Wormtongue-adjacent manipulators.

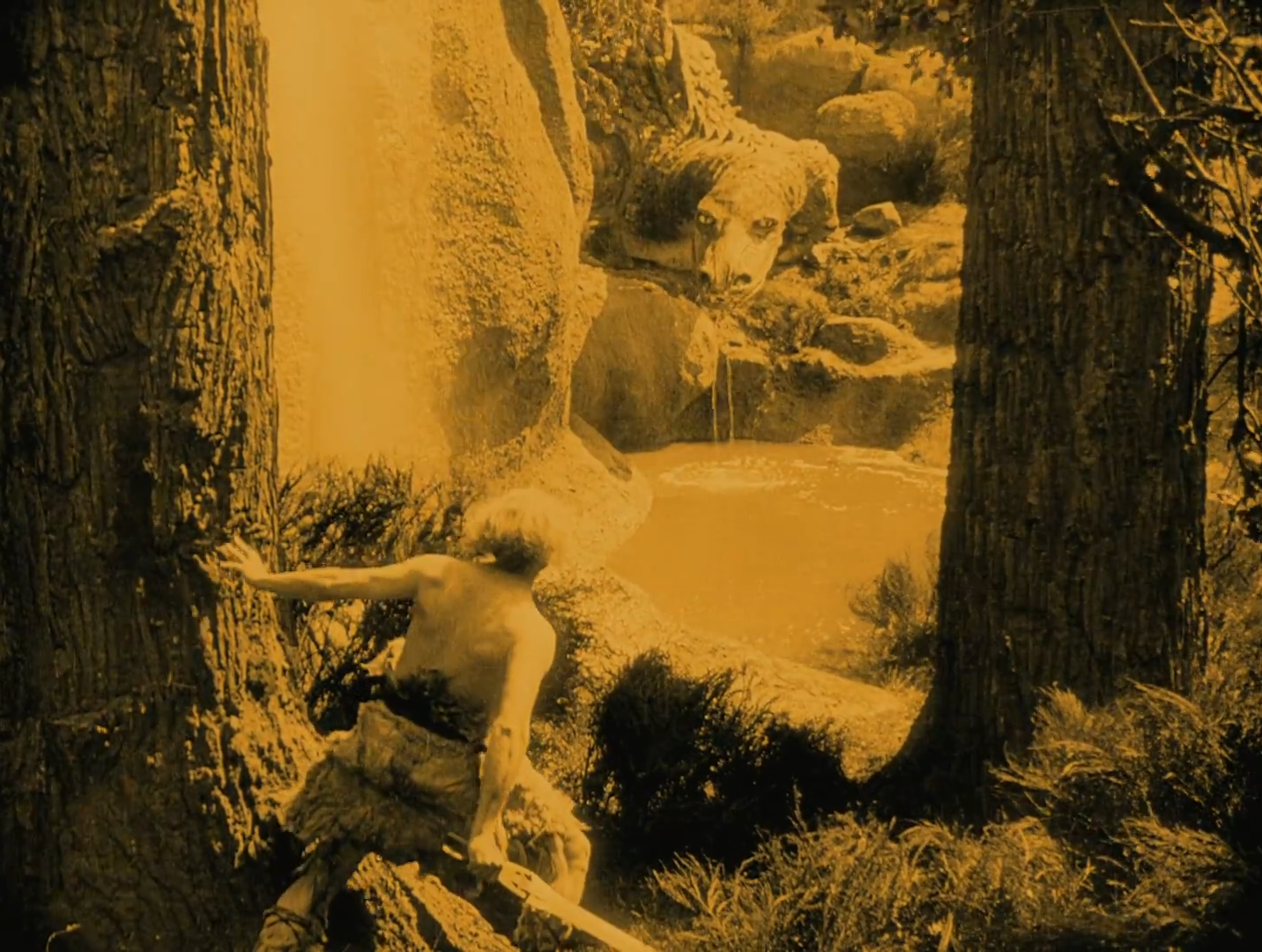

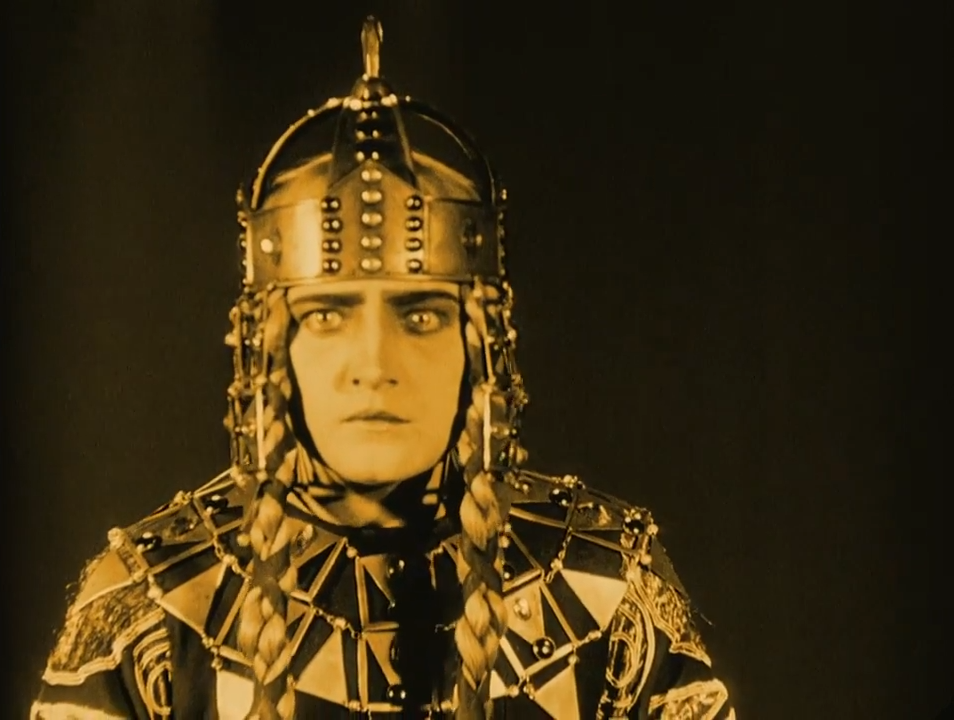

Lang is clearly attuned to the archetypes of this text, bringing each together in service of an epic narrative following our hero Siegfried’s rise, betrayal, and the vengeance that his widow seeks for his assassination. As the son of King Siegmund, he is a valiant figure destined for greatness right from the start, mastering the art of forging under the reclusive blacksmith Mime and immediately resolving to marry the beautiful Princess Kriemhilde, brother to King Gunther. His adventure through towering forests and misty swamps sees him fight a dragon, astoundingly brought to life as a giant, mechanical puppet that breathes real fire, and gain Achilles-like powers of invulnerability by bathing in its blood – that is, except for one spot on his shoulder which is shielded by a leaf. Later, his encounter with the crafty King of Dwarves brings him to the heart of a mountain where he claims the trickster’s net of invisibility, the legendary sword Balmung, and the rest of his enormous hoard.

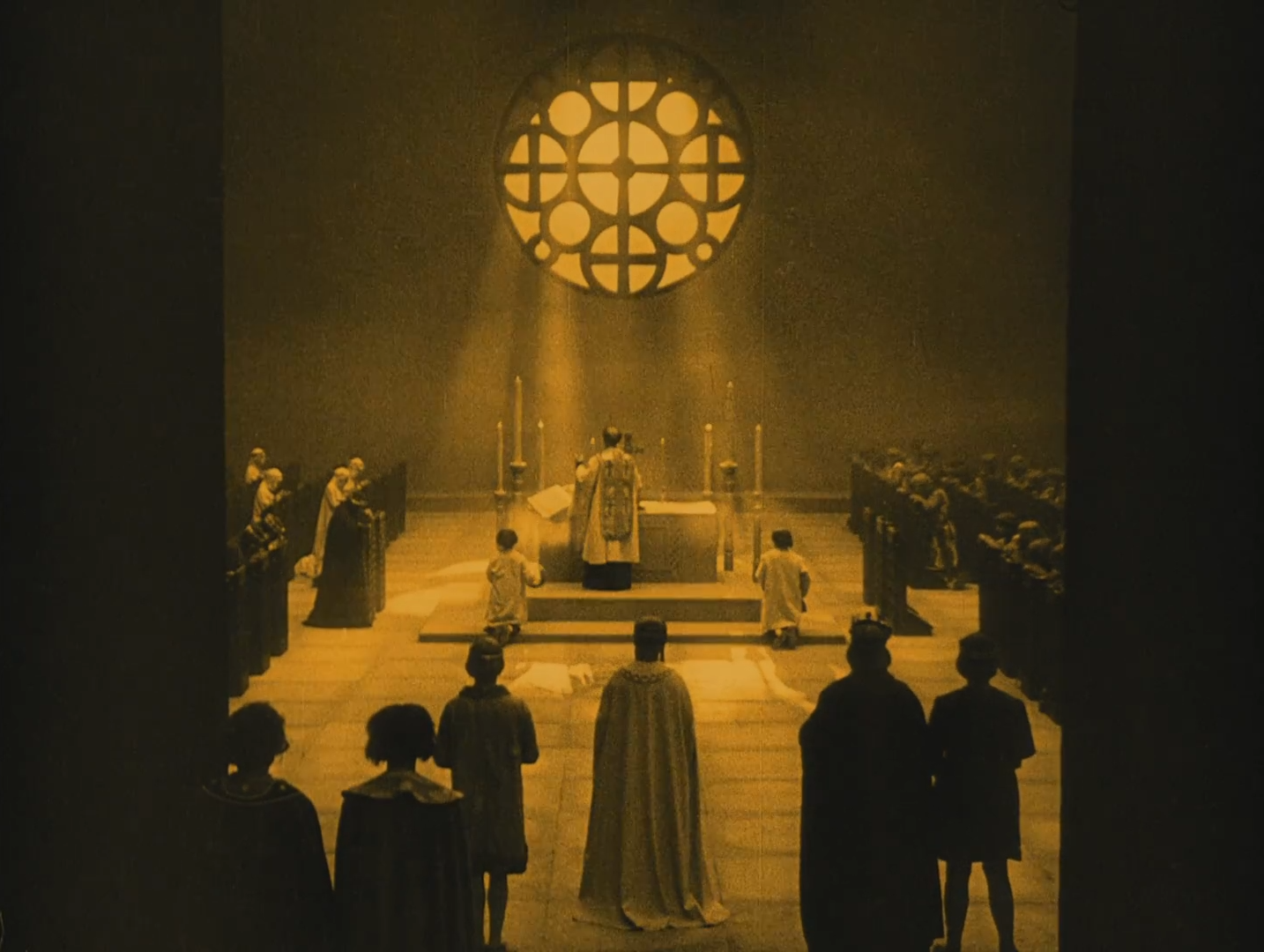

By the time Siegfried arrives at the Kingdom of Burgundy, he has amassed enough power and influence to win an audience with King Gunther. Taken with songs of Siegfried’s conquests, Kriemhilde longs to meet the brave adventurer, yet portentous dreams also warn her of future misfortune. Lang’s decision to render these visions in silhouetted cut-outs is a formal masterstroke, enlisting the help of animation pioneer Lotte Reiniger who only a couple of years later would use this technique to create cinema’s first animated feature, The Adventures of Prince Achmed. Here, we witness a collection of shapeless masses morph into birds, setting two black eagles against a white falcon who perishes in the assault. Kriemhilde may not immediately understand the dream’s symbolic significance, but given that this first part of Die Nibelungen is subtitled Siegfried’s Death, it isn’t hard for us to foresee their intertwining of fates.

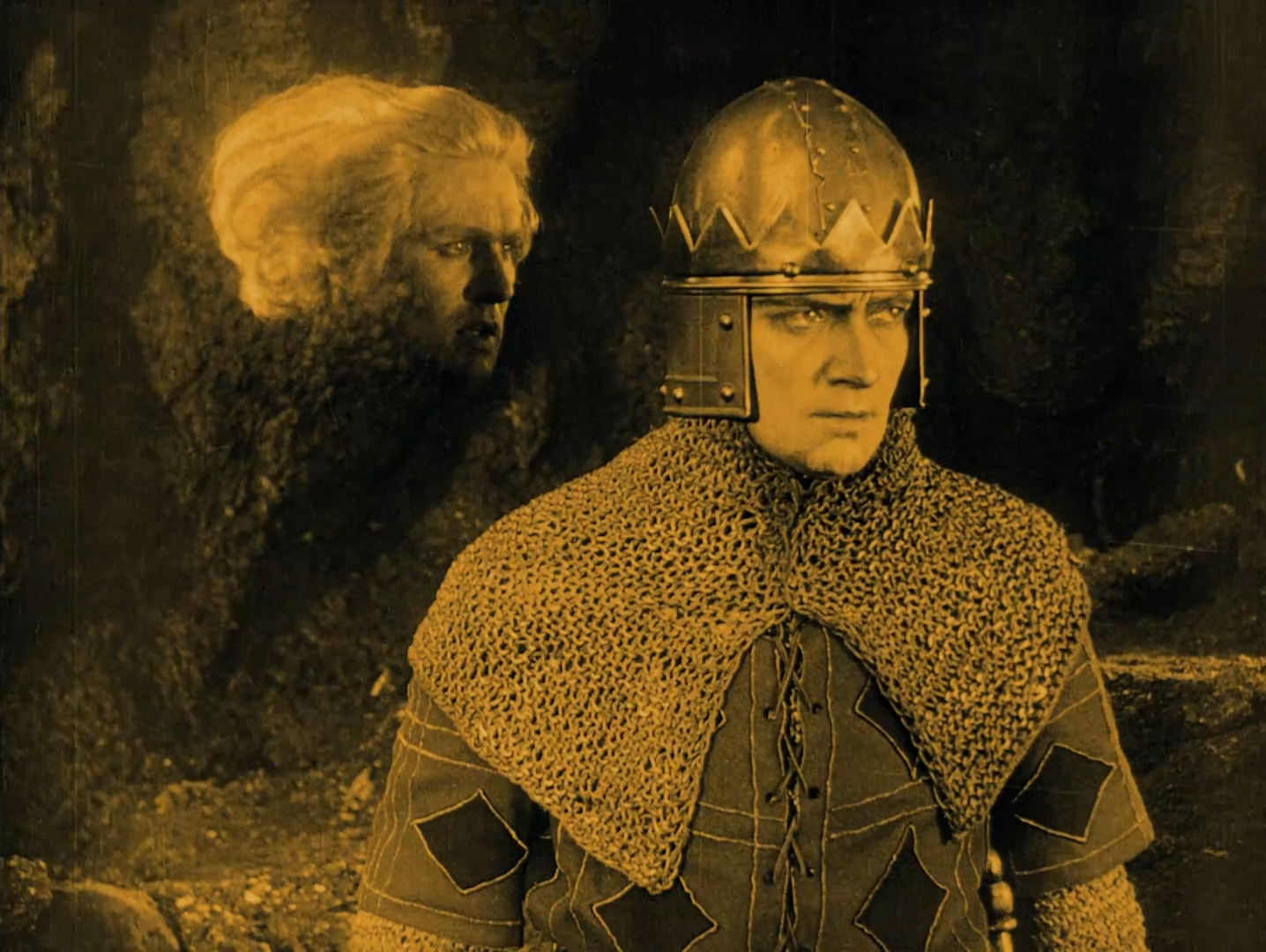

Lang’s daring manipulations of special effects do not end here either. To make the beautiful Kriemhilde his wife, Siegfried must first aid Gunther in winning Queen Brunhilde’s hand in marriage, yet it is plainly evident that the King is not up to the physical challenge of besting her in the three tasks she sets him. Fortunately, Siegfried has a cunning idea – with his net of invisibility, our hero can help the King cheat in the stone hurl, distance jump, and spear throw. Manifesting through faint double exposure effects, Siegfried secures victory for King Gunther, and thus marries Kriemhilde back in the Kingdom of Burgundy.

It is only a matter of time though before Brunhilde recognises her husband for the submissive weakling that he is, as well as the con which Siegfried has orchestrated, thus commencing Die Nibelungen’s political intrigue with her pursuit of retribution. Siegfried took her maidenhood, she lies to King Gunther, who is quick to turn on his friend. This “ravenous wolf” must be put down, he declares, and the duplicitous Hagen is more than happy to feed his madness.

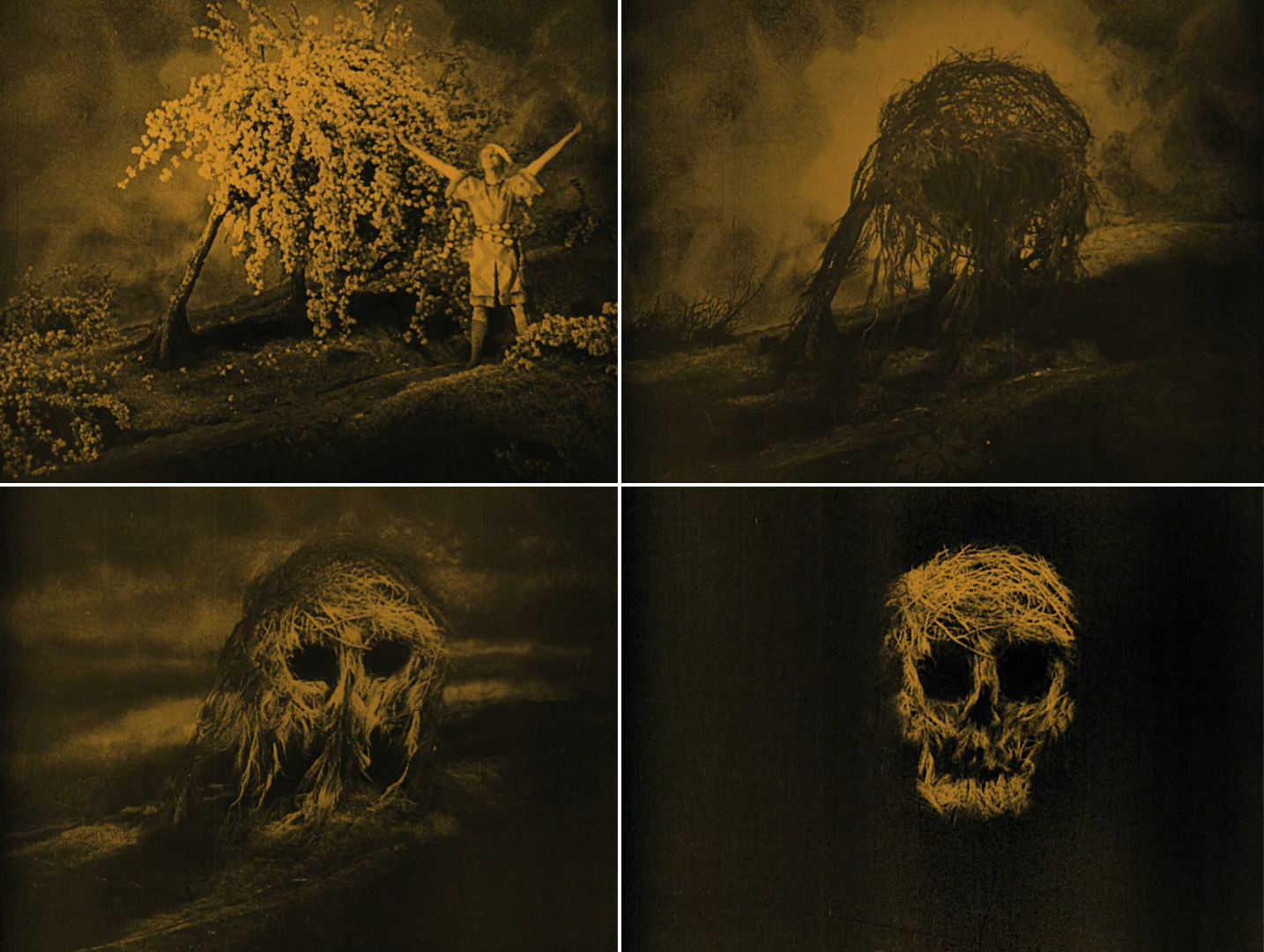

Kriemhilde meanwhile continues to be haunted by prophetic dreams of Siegfried being ripped apart by a boar and crushed by two mountains, yet even after she is tricked by Hagan to mark on her husband’s tunic the location of his sole weakness, still she remains naïve to the conspiracy which surrounds them. Only after Hagen has pierced Siegfried’s vulnerable shoulder with a spear during a hunt and brought his body back to the castle does Kriemhilde begin to grasp the treachery afoot in the Kingdom of Burgundy, and Lang once again draws from Georges Méliès’ playbook to visualise her love withering into grief. Recalling her dire dreams, she sees Siegfried standing with open arms in front of a blooming tree, which rapidly shrivels up before our eyes as he fades from view. Still the image continues to transform though, and through a skilful blend of lighting, editing, and production design, Lang menacingly morphs these dead branches into a large, sinister skull.

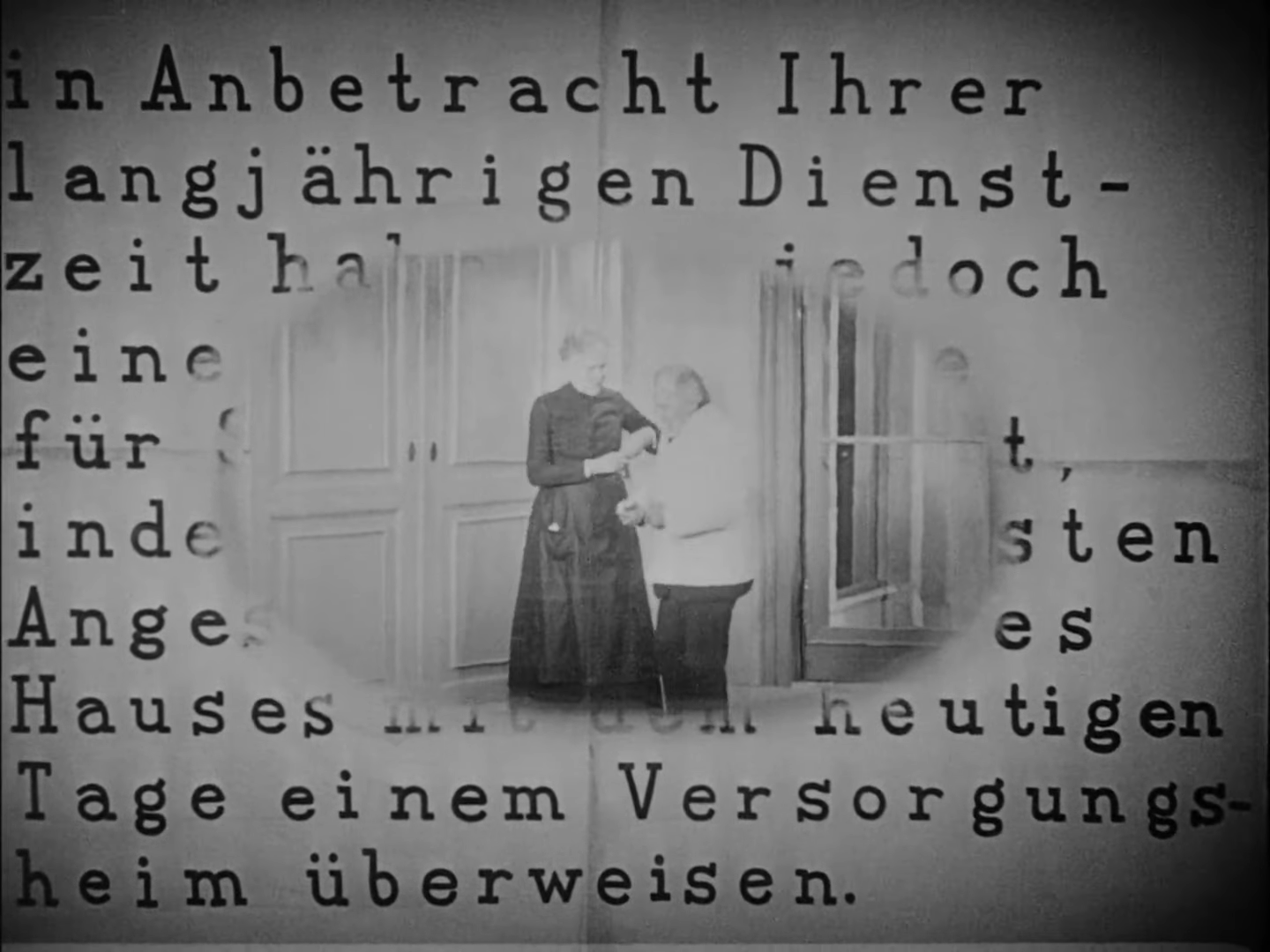

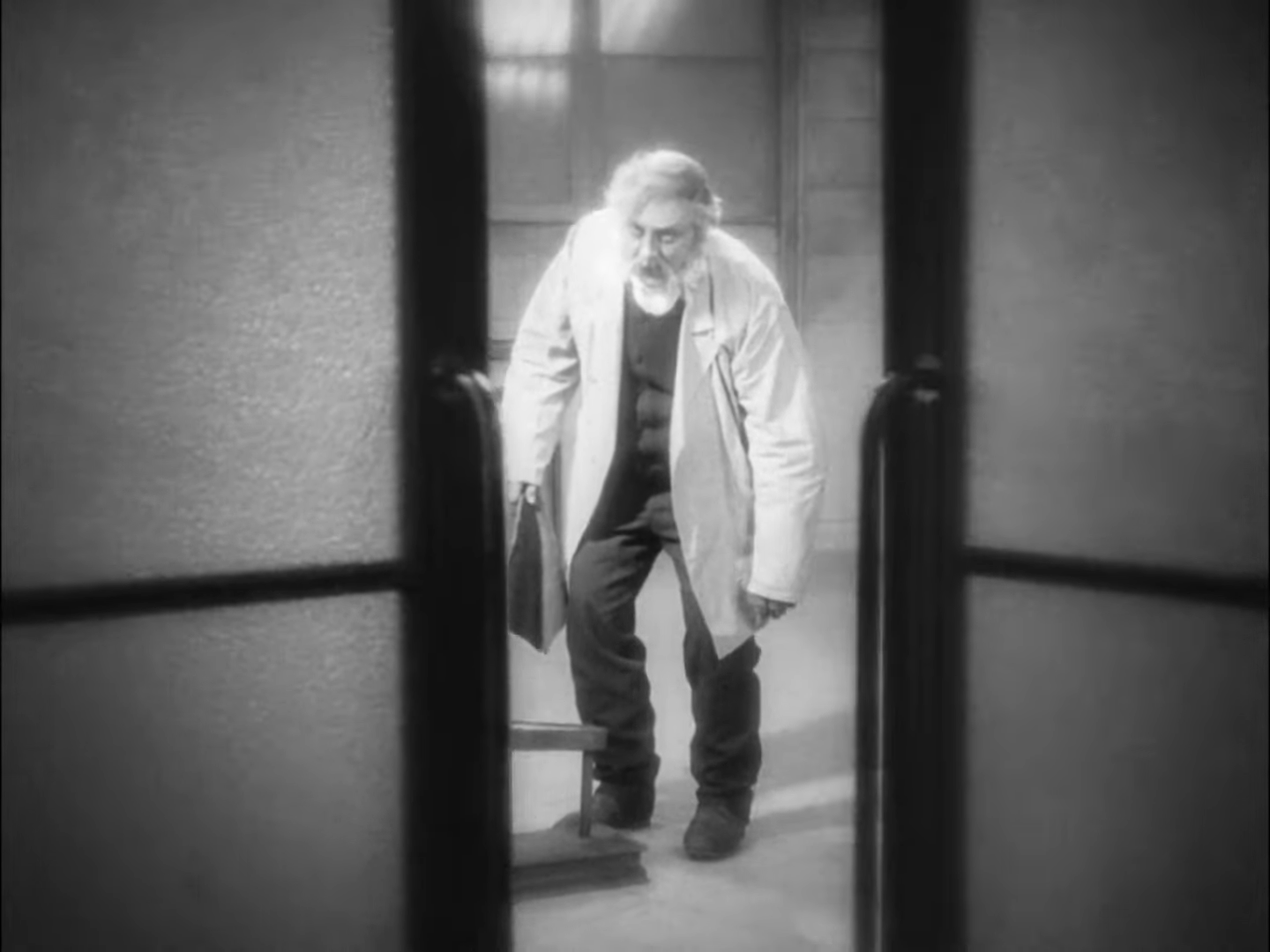

Never again do we see the light return to the princess’ eyes, with this newfound bitterness positioning her as the vindictive antihero of Die Nibelungen’s second part, Kriemhilde’s Revenge. Her patience is deadly and her string-pulling merciless, outdoing even the late Brunhilde who took her own life with gleeful satisfaction after Siegfried’s death. The transformation we see in Margarete Schön’s performance is tremendous, her face hardening as she finds a new husband in King Attila of the Huns and twists his pledge of loyalty into sworn vengeance against her family. His pleas to forget Siegfried go ignored, while his one-sided, lovesick devotion draws mockery from his own people, accusing him of falling under the “White Woman’s spell.”

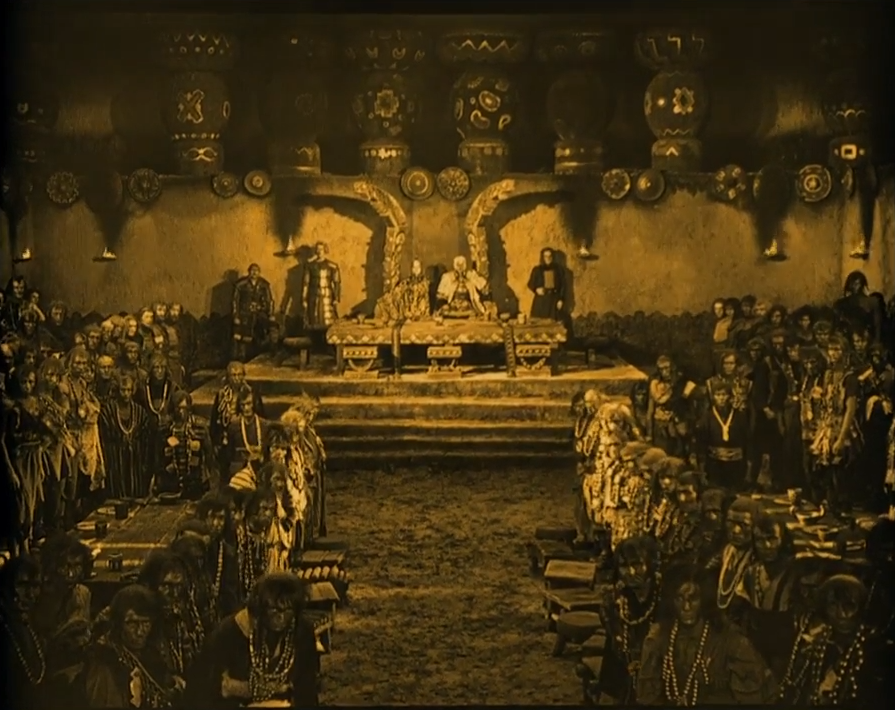

As we move deeper into the second part as well, Lang’s mise-en-scène notably shifts with it, distinguishing the immaculate symmetry and opulence of Gunther’s palace from the exotic, rugged design of the Hun kingdom. Instead of guards stationed in rigorous formations, Kriemhilde is greeted by hordes of barbaric warriors and gawking masses, while Attila’s primitive hall of scattered weapons and dirty floors chaotically illustrates his warmongering culture. As he ventures into battle too, tents made from animal hide host legions while campfires fill the air with black smoke. These people may be crude, yet in them Kriemhilde sees an opportunity to stir dissent, particularly when Gunther, Hagen, and the Burgundian soldiers eventually arrive on their steps as visitors for the Midsummer Solstice.

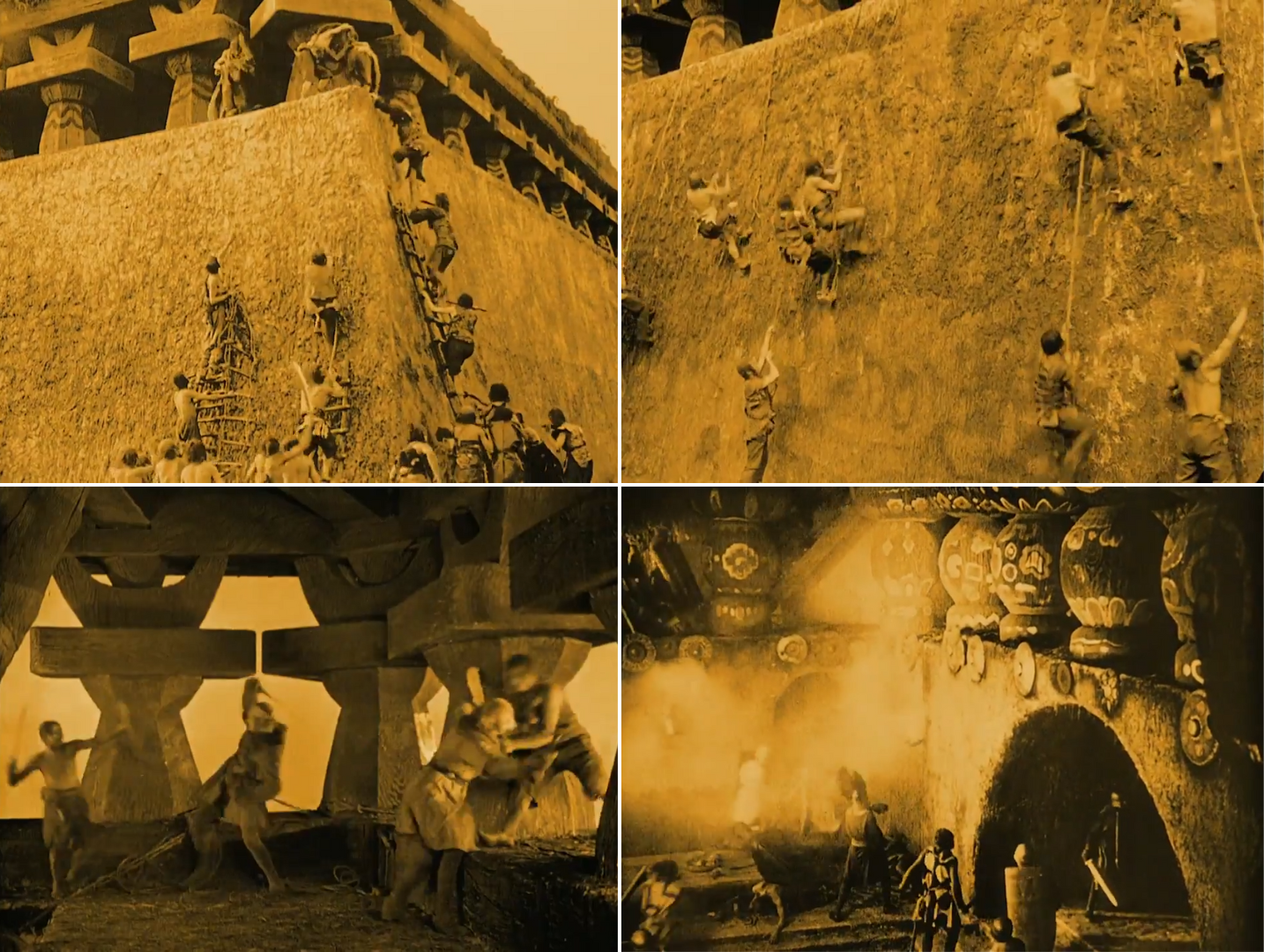

Although Lang swings away from the more fantastical elements of Die Nibelungen in Kriemhilde’s Revenge, the political manoeuvring only deepens. With Attila backing down from his pledge and asserting Hagen’s rights as a guest, Kriemhilde decides to take matters into her own hands, bribing the Hun warriors with gold to incite conflict during the feast. When the chaotic confusion ultimately leads Hagen to slaughter Attila and Kriemhilde’s son though, all civility is officially thrown out the window. In the final act of this five-hour duology, Lang stages an epic battle of sieges, hostages, and executions, simultaneously drawing inspiration from the fall of Babylon in D.W. Griffith’s Intolerance and setting a standard of cinematic medieval warfare that Jackson would later strive to match in The Lord of the Rings.

Despite her success in stoking hostility and trapping the Burgundians inside the hall though, Kriemhilde is far from satisfied. “I died when Siegfried died,” she coldly laments, turning away from the sentimental innocence of her youth. With her son as the first casualty of this war, her soul blackens beyond redemption, callously rejecting her brothers’ pleas for mercy when they refuse to turn over Hagen. It is all too fitting that this woman who seeks the destruction of her family should order the Huns to attack their own infrastructure, and demand her most faithful vassal to kill his son. Heritage means nothing to a woman so twisted by rage that her only loyalty is to a dead man, and it is through her own selfish actions that she ultimately sets in motion the downfall of two great civilisations.

In the flames and black smoke which billow up from the burning hall, a blazing emblem of Kriemhilde’s barbaric legacy is born, before eventually collapsing beneath its own weight. “Loyalty, which iron could not break, will not melt in fire,” Hagen’s men staunchly proclaim, refusing to give up their leader even as they are crushed by the falling roof. Lang’s practical effects are as spectacular as ever here, yet tragedy reigns in the wake of such a daring set piece, with Gunther and Hagen emerging from the ruins to face their executioner.

Although Kriemhilde finally delivers the vengeance she has long sought against her kin, there is no great reward awaiting her on the other side of this conquest. Die Nibelungen has few survivors, as even the tyrannical princess soon falls to the blade of her own disillusioned sword master. From the wondrous fantasy of this legend’s beginning, love withers into grief, and finally begets contempt, violence, and widespread devastation. Lang orchestrates legend with a composer’s precision, and through a finale as colossal as the stories which inspired it, he concludes an operatic spectacle that continues to reverberate cinematic fanfares, choruses, and cadences through the ages.

Die Nibelungen is currently in the public domain and available to watch for free on YouTube.