Fritz Lang | 4hr 29min

Among the various despicable villains of German expressionism, many possess a common set of nefarious skills, manipulating their prey through hypnotism, disguises, and trickery. From Nosferatu to Dr Caligari, their methods are deeply invasive and psychological, turning innocent civilians into pawns for their grand, evil schemes. In this monumental landmark of the movement though, Dr Mabuse is not some inhuman aberration or madman recklessly testing his powers for their own sake, but an intelligent, methodical mastermind, patiently plotting each step of his rise to power. He may be “whirling laws and gods around like withered leaves,” but he is also the calm centre of the storm, sitting comfortably in his office while sending entire stock markets crashing down around him. A fearful mistrust directed towards shady authority figures was the great insecurity of post-World War I Germany, and within Dr. Mabuse the Gambler, Fritz Lang distils it down to a single, megalomaniacal genius.

There may be few films pushing five hours long which possess a narrative as effortlessly breezy as this too, building on the epic crime story conventions that Louis Feuillade had innovated in his ten-part silent serial Les Vampires. With seductive femme fatales, elaborate conspiracies, and bastions of the law looking to bust them wide open, Lang and his co-writer Thea von Harbou essentially set the proto-film noir standard, crafting a thrilling plot that spans the urban alleyways and gambling clubs of Weimar Germany. There is a distinct literary quality here as well, breaking this film down into a dozen succinct chapters, which itself isn’t surprising given its basis in a book by Luxembourgish writer Norbert Jacques.

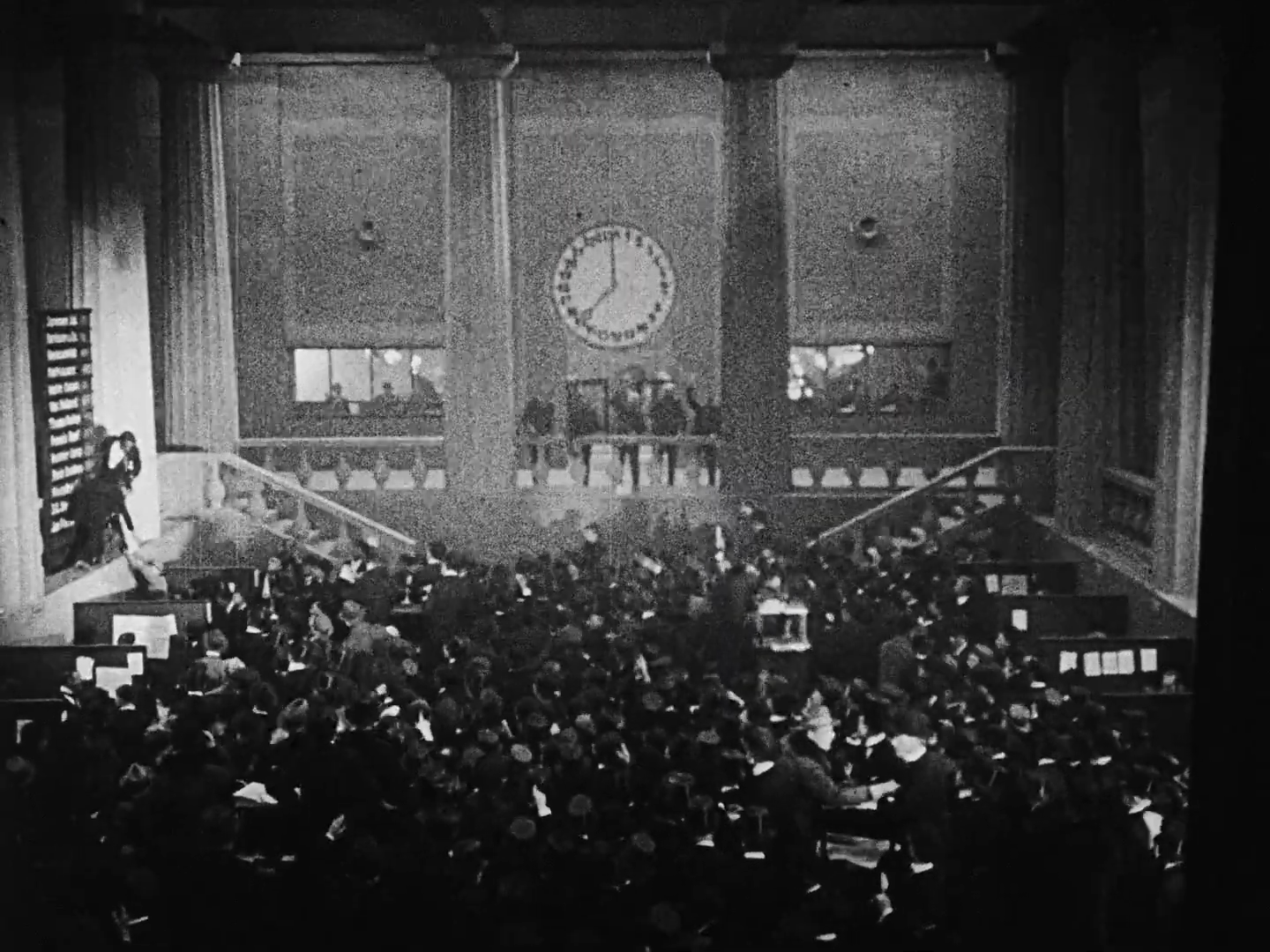

Even with one foot in the world of novels though, Lang still recognises cinema as a nascent art form with its own unique visual language and creative potential. There is nothing about this dark, warped vision of 1920s Germany which feels confined by its prose, exploding geometric shapes out across modernist sets designed at skewed angles. There is barely a curve in sight when state prosecutor Norbert von Wenk infiltrates a posh gambling club, intending to catch the mysterious fraudster, the Great Unknown, who has been adopting various identities and hypnotising opponents into losing games of poker. Doorways are shaped in asymmetrical, triangular arches, and even the chairs are unusually shaped to rise to a pair of jagged points, while men and women in fine formalwear meet over rectangular tables. Elsewhere, the giant stock exchange brimming with frenzied masses is far more blockish in its imposing structure, hinting at similar set designs that Lang would use in Metropolis a few years later, and striking a harsh disparity against the narrow, crooked alleyways outside.

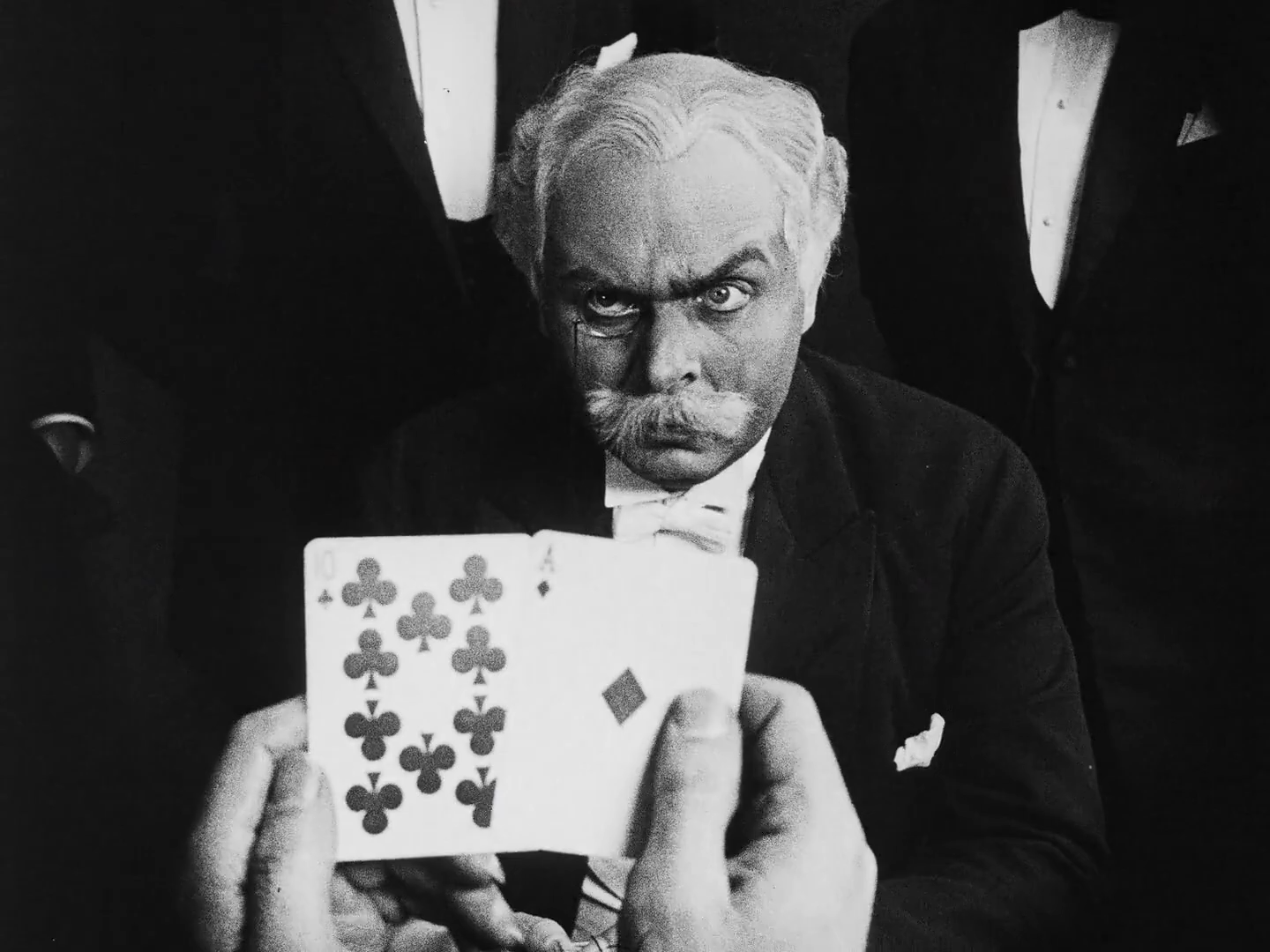

In terms of more contemporary comparisons, this is a city similar to Batman’s Gotham, with pervasive corruption infiltrating every corner. In this case though, it can all be linked back to that central figure pulling strings behind the scenes, sending his henchmen out into theatres, trains, and prisons to carry out his will. Even more unsettling is just how willing they are to die for him, with the infatuated cabaret dancer Carozza choosing to take poison rather than break under Wenk’s interrogation. Each of the men are depicted as degenerates on some level, though it is Rudolf Klein-Rogge who remains the most compelling screen presence as the slippery Dr. Mabuse, transforming his entire look and manner from one disguise to the next. The black makeup lining his eyes draws us even deeper into his mesmerising gaze too, dark with intelligence and cruelty, and at times connecting directly with the camera.

The evil depths to which Mabuse plunges never seem to end, and so for Wenk the stakes keep growing. Though they remain unaware of each other’s identity for some time, this conflict is incredibly personal for both, especially when Mabuse’s newest target and Wenk’s recent aide, Edgar, perishes at the hands of the mastermind’s brawny hitman during a police raid. The cold murder of such a major character two hours into this epic comes as a brutal shock, especially at a point in the narrative when our protagonists seem right on the verge of pinning Mabuse down once and for all, though this is not even the doctor’s most despicable deed in the film.

It is mere chance that brings Count Told knocking at his door, seeking psychological treatment while ignorant to the fact that his own wife is imprisoned in his basement. The opportunistic Mabuse is sure to capitalise on this turn of events, taking him into his custody too. Now cut off from his old life and under the care of a man actively degrading his sanity, the Count finds himself tormented by ethereal hallucinations, manifesting through Lang’s haunting use of double exposure. His arc only concludes when he is hypnotically compelled to slash his own throat, thereby bringing the doctor’s experiment to a vicious end.

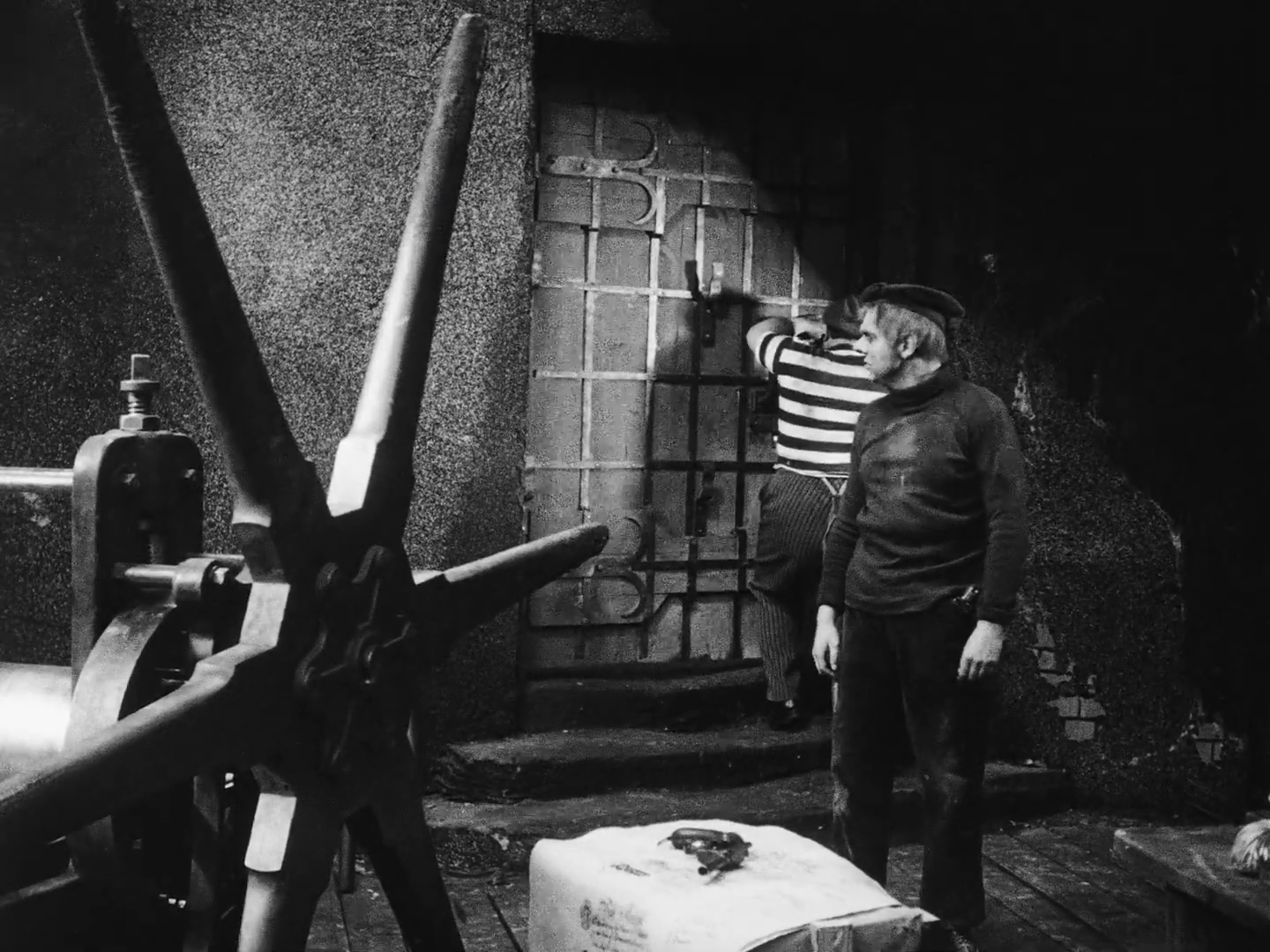

Given his penchant for manipulating and destroying the psyches of others, Mabuse’s own eventual mental breakdown makes for a tantalising piece of poetic justice. At this point, his hideout has been sniffed out and surrounded by Wenk and his men, and there is even a touch of D.W. Griffith’s parallel editing here as we briskly cut between both sides of the tremendously staged siege. The scale of Lang’s thunderous set piece here is a fitting climax to such a sprawling film, and even more gratifying are the ghostly returns of all those whose deaths Mabuse has been responsible for.

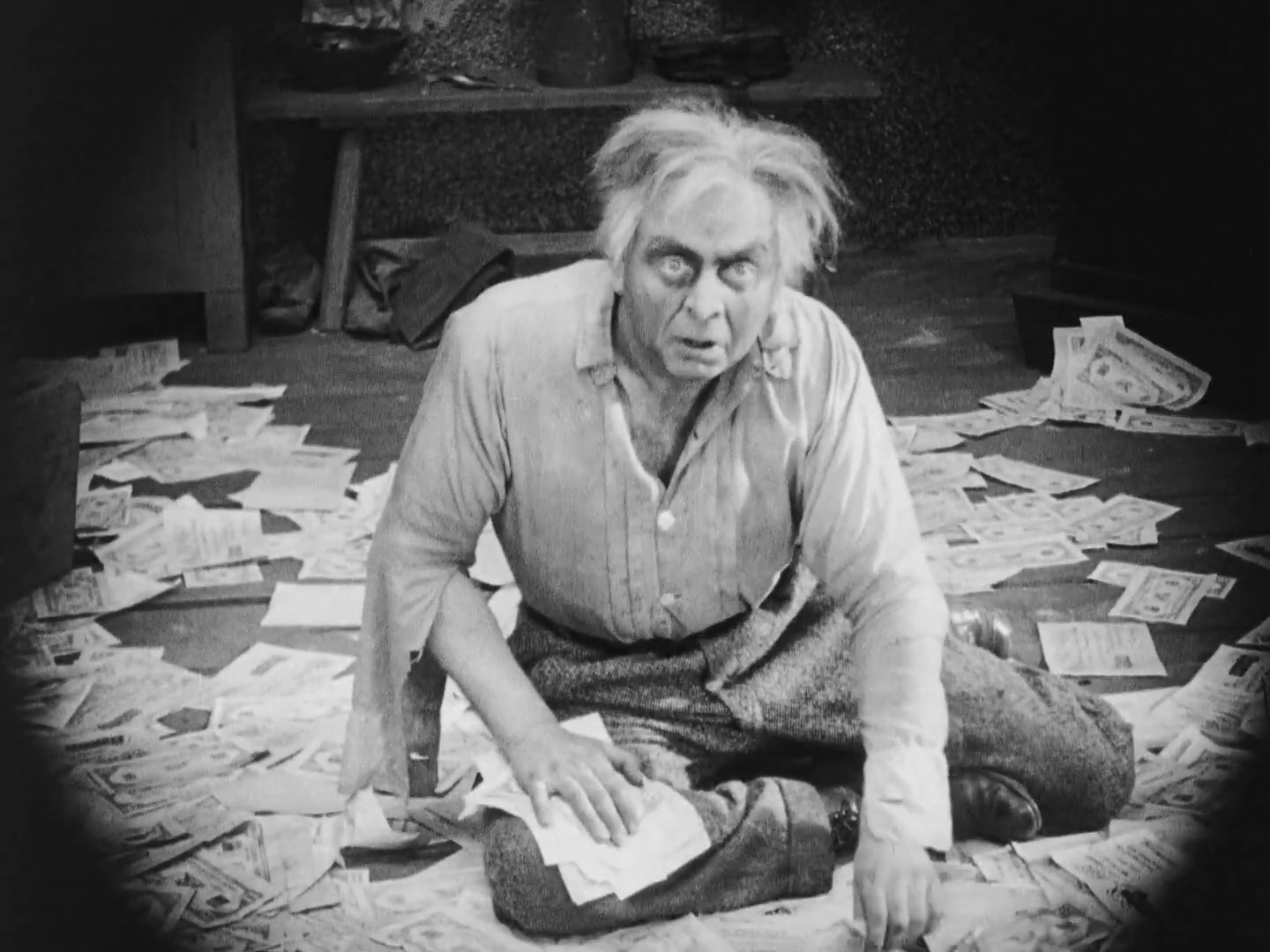

The tables are well and truly turned as the phantoms force him into a game of poker and accuse him of cheating, drawing parallels to his torture of the Count, before giant, mechanical demons manifest before his eyes. The monsters of modernity that Mabuse once exploited have come to exact their own vengeance, so that by the time Wenk finally catches up with the doctor, he is little more than a catatonic lump, slouched on the floor and weakly grasping at the loose money bills around him. Those who dabble in the mysterious depths of the human mind may find themselves consumed by the very forces they manipulate, this coda reasons, bringing a touch of hope to an otherwise grim tale. At its core, Dr. Mabuse the Gambler is deeply concerned with those authoritarian evils looking to exploit an unstable society, and right up until its final frames Lang refuses to hold back in painting them out with the harsh, jagged strokes of his extraordinary expressionist design.

Dr. Mabuse the Gambler is currently in the public domain, and is available to watch on free video sharing sites such as YouTube.