Highest 2 Lowest (2025)

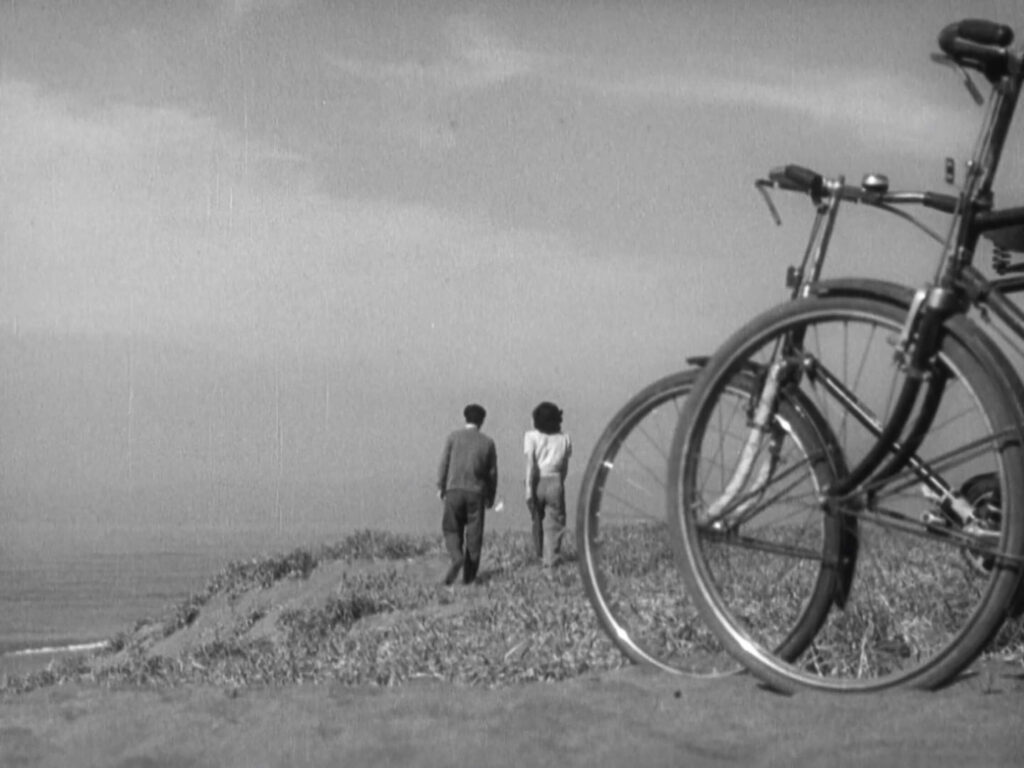

Where a better Spike Lee film would consistently swing hard for audacious set pieces, Highest 2 Lowest teases us with glimpses of the Kurosawa adaptation that could have been, settling for a bland remake of a once-thrilling crime plot and moral dilemma that severely flattens whatever tension remains.