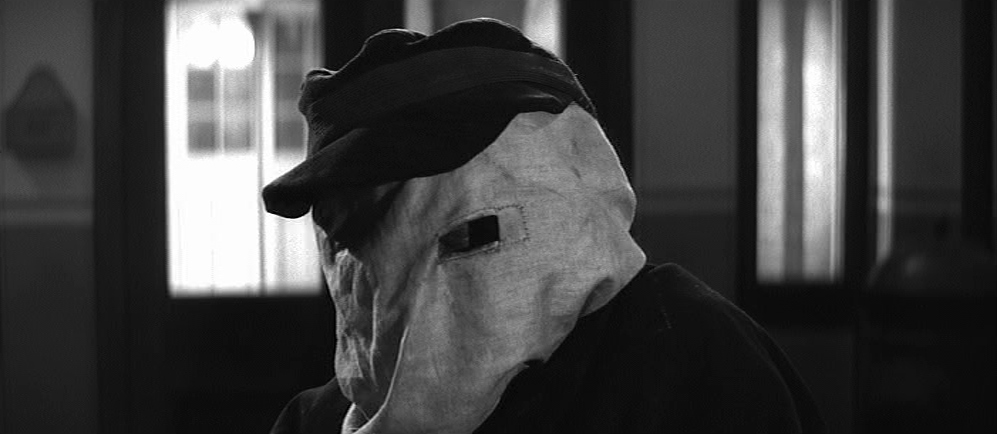

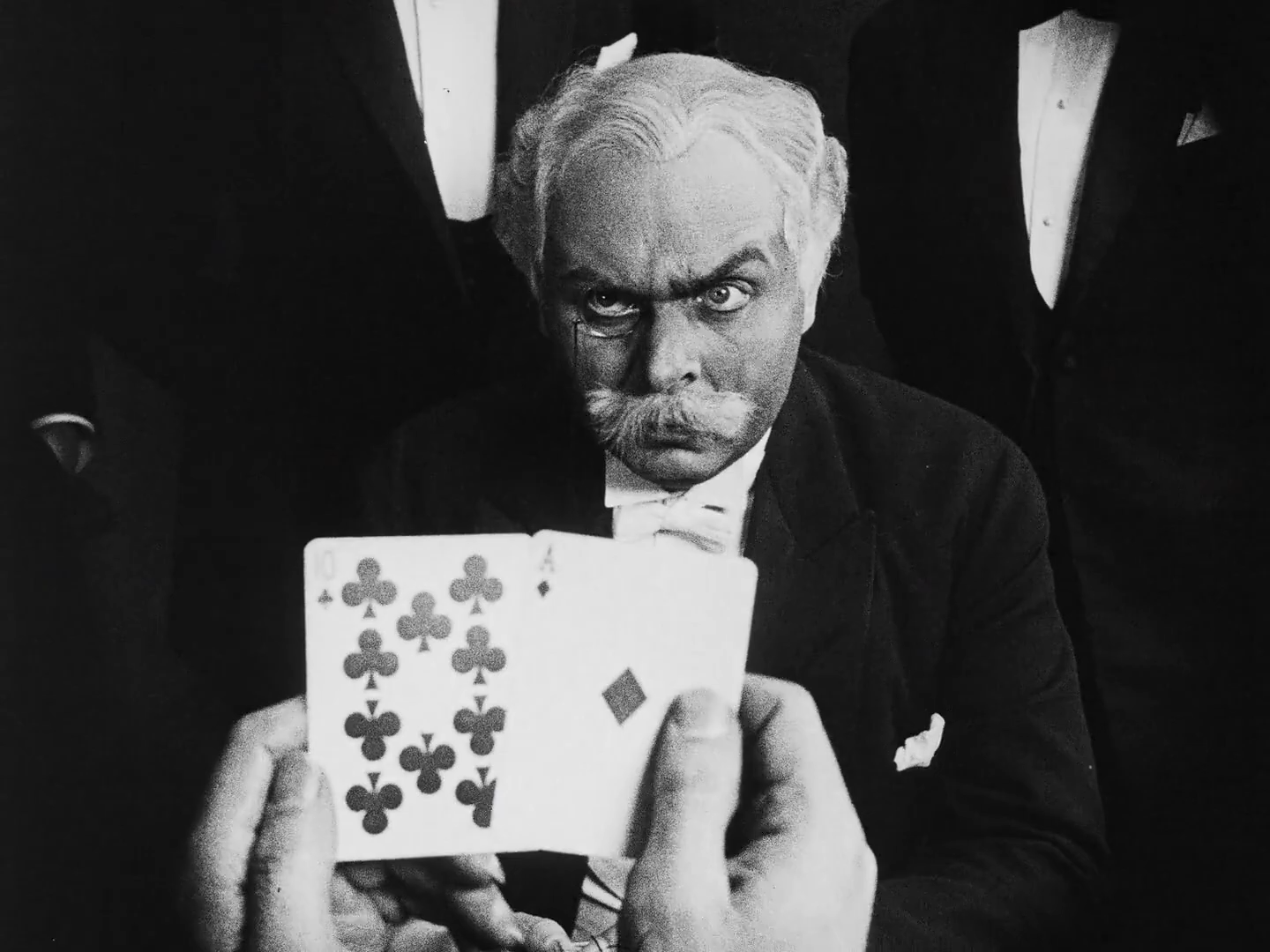

Throne of Blood (1957)

Akira Kurosawa’s landscapes of ambition, fate, and consequences make for a perfect marriage with Shakespeare’s Macbeth in Throne of Blood, formally integrating the narrative’s treacherous power plays with historical elements of Japanese Noh theatre, and mounting the forces of nature and destiny against the dishonourable samurai at its centre.