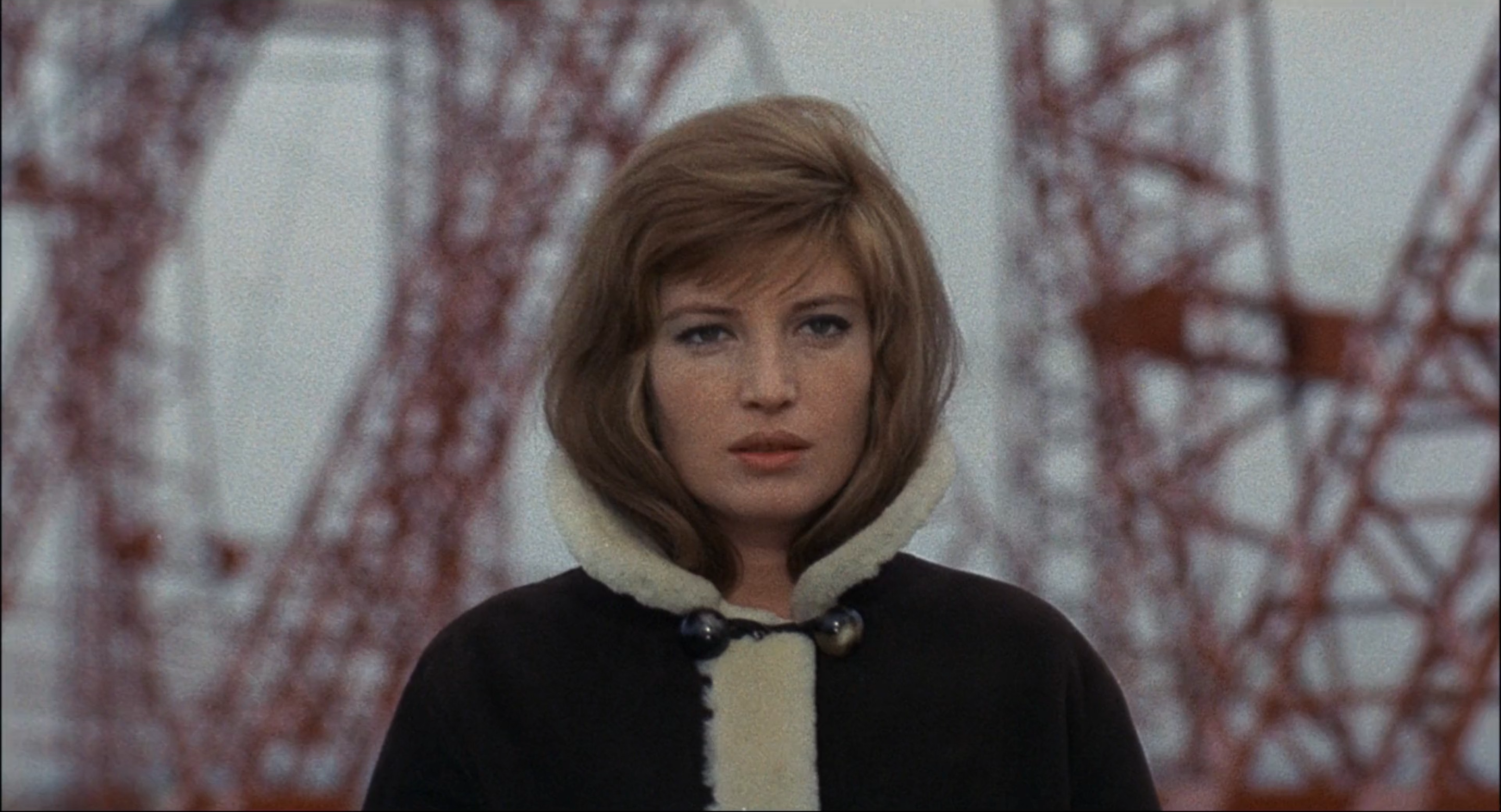

Variety Lights (1950)

Federico Fellini’s love of theatre would take on great symbolic meaning in his later films, but it emerges quite directly here as the setting of his directorial debut Variety Lights, fuelling the drama between the flighty members of a travelling troupe dreaming of fame, money, and love.