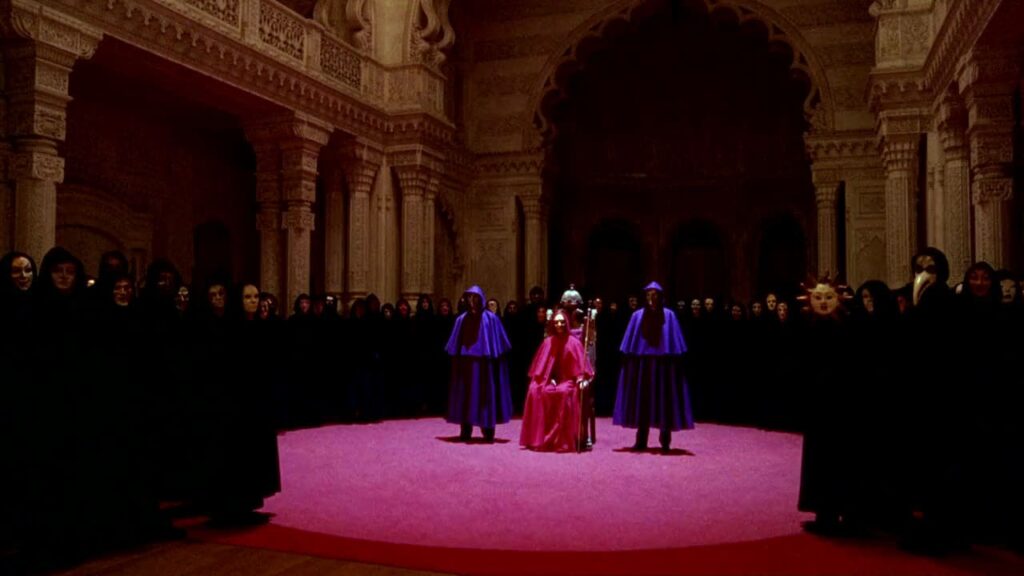

Alexander Nevsky (1938)

Alexander Nevsky may not possess the formal innovation of Sergei Eisenstein’s avant-garde silent films, yet this venture into sound cinema unfolds a historic clash of medieval armies with incredible finesse, celebrating a Russian folk hero whose tale resonates across eras and cultures.