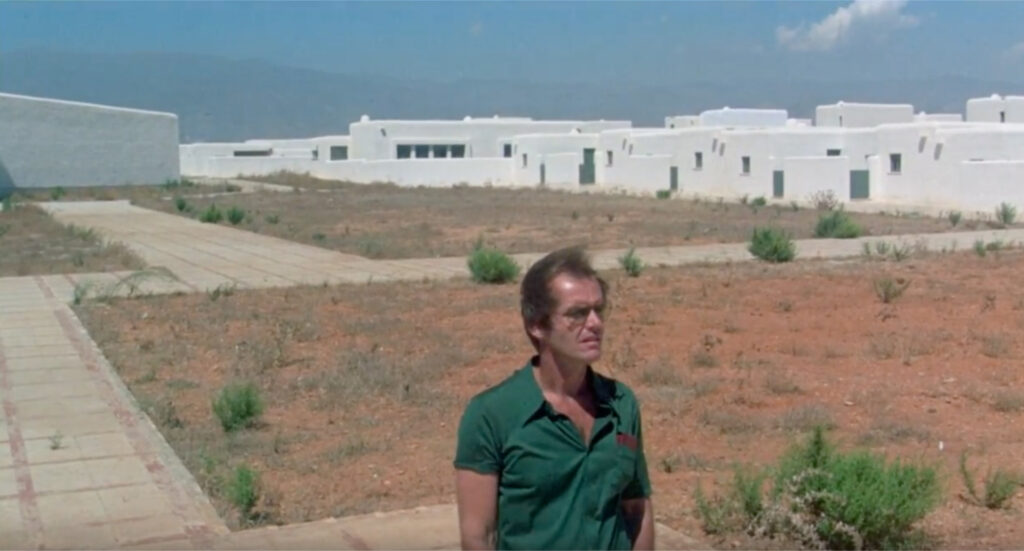

Last Tango in Paris (1972)

The anonymous affair which widower Paul and young actress Jeanne conduct makes for a warped power dynamic in Last Tango in Paris, and Bernardo Bertolucci is unafraid to plunge the crude depths of their precarious arrangement, prodding at raw, psychological wounds that explode with love, grief, and violent anger.