Guillermo del Toro | 2hr 30min

Victor Frankenstein’s reanimation of a dead body does not arrive with thunderous exclamations of “It’s alive!” in Guillermo del Toro’s adaptation of the Gothic novel. In fact, this incarnation of the mad scientist initially appears to outright fail his endeavour, retreating from his laboratory and retiring to bed in defeat. When the sun rises though and he finds the newborn Creature looming over him in bewildered wonder, he offers it a tender embrace. “Victor,” the scientist utters, indicating toward himself. “Victor,” the Creature mimics, similarly pointing at his chest, and thus a paternal parallel between creator and creation is immediately drawn. In this vision of Frankenstein, one is not simply an offspring of the other. Here, the Creature is an inextricable part of his maker’s identity – his obsession, his shame, and ultimately his downfall.

When we trace Victor’s audacious dream of birthing life from death back to Victor’s own fractured family history, this twisted union becomes even more unsettling. “There is no spiritual content in tissue, and no emotion in a muscle,” his cold, withholding father taught him in physiology lessons, stripping the human form of wonder and asserting the irreversible mortality of all living things. When Victor’s mother passed away giving birth to his brother William, there was no grace left in their household to ease his father’s abuse. “She who was life was now death,” the scientist muses, reflecting on that primordial drive to transcend his father’s limitations and conquer that which took his mother. Indeed, Victor may defy the laws of biology, yet triumph over his own nature he cannot. Instead, he resentfully condemns his creation to the same corrosive cycle of paternal cruelty and maternal absence that once poisoned his own innocence, offering an inheritance of unfulfilled longing.

It was only a matter of time before del Toro reimagined this literary classic in his own lush, baroque style, especially given how long it gestated in his creative mind as an unrealised vision. He has breathed life into many sympathetic monsters throughout his career, though none so legendary as this cobbled creation, “assembled from refuse and the discarded dead.” Divorced from the familiar iconography of the 1931 monster movie, del Toro’s Frankenstein strips away the camp exaggeration, pursuing a far more faithful, psychologically complex rendering of Mary Shelley’s characters and narrative structure. The few alterations he makes to the source material only serve to deepen its existential tragedy, most significantly condemning the Creature to the eternal torment of immortality, though del Toro largely leaves the skeleton intact. Much like Shelley’s original framing device, the mirrored flashbacks here unfold like a pair of confessions, leading us into Frankenstein’s epic, haunting tale by way of a Danish Navy ship.

Stranded in the frozen Arctic waste, it is there where the crew gives refuge to Victor, and temporarily sinks his mysterious, inhumanly strong pursuer into the icy ocean. He takes the role of narrator for Part I, divulging the great experiment that led to his ruin, before the Creature emerges from the depths to offer his own mournful perspective in Part II. Where Victor’s tale ends with him attempting to destroy his creation, believing it possesses the rotten heart of its progenitor, the Creature’s begins with its survival amid the burning wreckage of its home – a rebirth into “merciless life.” At its core, Frankenstein is a dialogue between a neglectful parent and spurned child, and del Toro’s fatalistic treatment leans fully into this toxic, bitter dynamic.

Especially once we consider Mia Goth’s dual roles as both Victor’s mother and his love interest Elizabeth, a distinctly Freudian angle begins to emerge, filling the void left by the former’s death. Elizabeth is William’s fiancée after all, yet Victor cannot bear to lose this paragon of purity to his own brother, and thus seeks to possess her as a means of reclaiming what death stole from him. When she discovers the infantile Creature and begins to treat him with maternal kindness though, Victor’s jealousy flares, hardening his resentment toward this grotesque usurper of the tenderness he once craved. Twice does he blame him for murders that he himself committed, passing his treacherous sins onto his child, and thus disowning the part of himself he cannot bear to face. In the Creature, Victor is given a chance to right the wrongs inflicted upon him by his father – but by repeating the mistreatment he endured as a boy, he simply raises a monster in his own broken image.

The colour palette that del Toro draws between the two female anchors in Victor’s life only intensifies this psychological tension too, cloaking his mother in an ethereal red veil, while Elizabeth is primarily costumed in ravishing green dresses. Even beyond her stylish wardrobe, del Toro weaves these vibrant hues all through his elaborate mise-en-scène, pitting the aggressive quest for immortality against the fragile sanctity of life itself. Wreathed in flames and promising Victor dominion over mortality, nightmarish visions of a scarlet angel further enrich his chromatic symbolism, eerily channelling the ‘Angel of Destruction’ from Shelley’s primary inspiration, ‘Paradise Lost’. The dichotomy of ruin and redemption tugs at the soul of del Toro’s Frankenstein, and through his vibrant, Gothic splendour, imbues it with a mythic weight that entirely dwarfs its lonely characters.

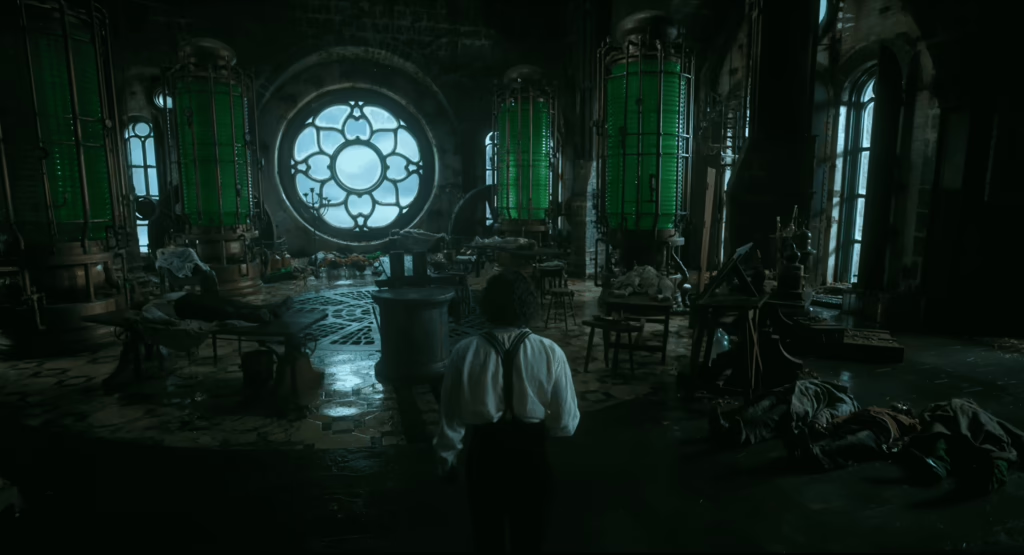

Del Toro’s soaring visual ambition is announced right from the start in the sweeping tracking shot across the frozen Arctic landscape, illuminating the cool blue desolation with a fiery orange warmth, though it truly begins to lift off in the ornate manor of Victor’s childhood. Wide-angle lenses and tracking shots recall the painterly elegance of Crimson Peak, and once we reach the storm-lashed laboratory where his experiment comes to life, Frankenstein erupts into a fever dream of flesh and machinery. There, a high relief sculpture of Medusa bears horrified witness to the grotesque genesis of a similarly forsaken monster, while colossal batteries bathe the cavernous chamber in alternating washes of red and green. Smoke fills the air and crane shots rise high above Victor as he furiously attempts to defy nature, and just as lightning strikes the outstretched body, the camera itself tunnels through its squelching innards where a heart begins to beat and neurons spark to life.

Far from the hulking, moaning brute that was Boris Karloff’s portrayal of the Creature, Jacob Elordi’s is a pale, sinewy patchwork of parts, clumsily stumbling through a hostile world with a raw, primal vulnerability. Though he has already made an impressive step outside of teen rom-coms and into more demanding dramatic territory, Frankenstein cements his evolution as an actor of haunting depth, depicting the full life cycle of this tragic outcast from his trembling infancy to his inevitable loss of innocence. He is quick to learn the cutthroat hostility of a world that preys on weakness, finding its only glimmer of kindness in a blind, elderly man who cannot see his misshapen form. Elordi’s voice emerges in a deep, resonant stutter as this unlikely father figure teaches him to speak, and eventually breaks into a guttural roar when the man’s family inevitably discovers and attacks him.

“They will hunt you and kill you just for being who you are,” the Creature reflects, settling on a truth that finds its harshest expression in his bond with Victor. This is a father who gave him life, yet denies him love, even in the form of a constructed female companion who might ease the agony of unending exile. As a result, when the Creature eventually reunites Elizabeth, del Toro effectively closes Frankenstein’s Freudian loop. Her absence has left a maternal void in his life, and now as Victor’s sins come full circle, she becomes the axis upon which father and son fatally collide. Grace remains forever out of reach for those trapped in cycles of inherited cruelty, destroyed by the very hand which reaches for its nurturing embrace, and tinging the narrative climax with a greater sorrow than the Creature’s violent retribution in Shelley’s denouement.

Del Toro does not deviate from the source material without purpose after all, and by drawing Victor and the Creature together one final time, he offers an unexpectedly tender resolution. Peace may bloom from a paternal bond that has been abandoned, condemned, or desecrated, Frankenstein contemplates, yet it may be mercifully saved in accepting one’s irrevocable tether to the past and fragile hope for the future. Through operatic mythologising and cinematic splendour, del Toro magnificently elevates Shelley’s tale of hubris into a rueful, elegiac meditation on kinship, leaving its only salvation in the hands of those who dare to love what cannot last.

Frankenstein is currently streaming on Netflix.