Yorgos Lanthimos | 2hr

Despite Teddy’s unhinged conspiracy theories that aliens have infiltrated Earth’s elite, his suspicion isn’t entirely off-base. Even after kidnapping the CEO of pharmaceutical company Auxolith, torturing her in his basement, and demanding a meeting with her alien emperor, still he emerges as Bugonia’s most tragic figure. We laugh at his far-fetched delusions, yet next to the disdainful pragmatism and icy composure of his captive Michelle Fuller, sanity feels like a relative concept.

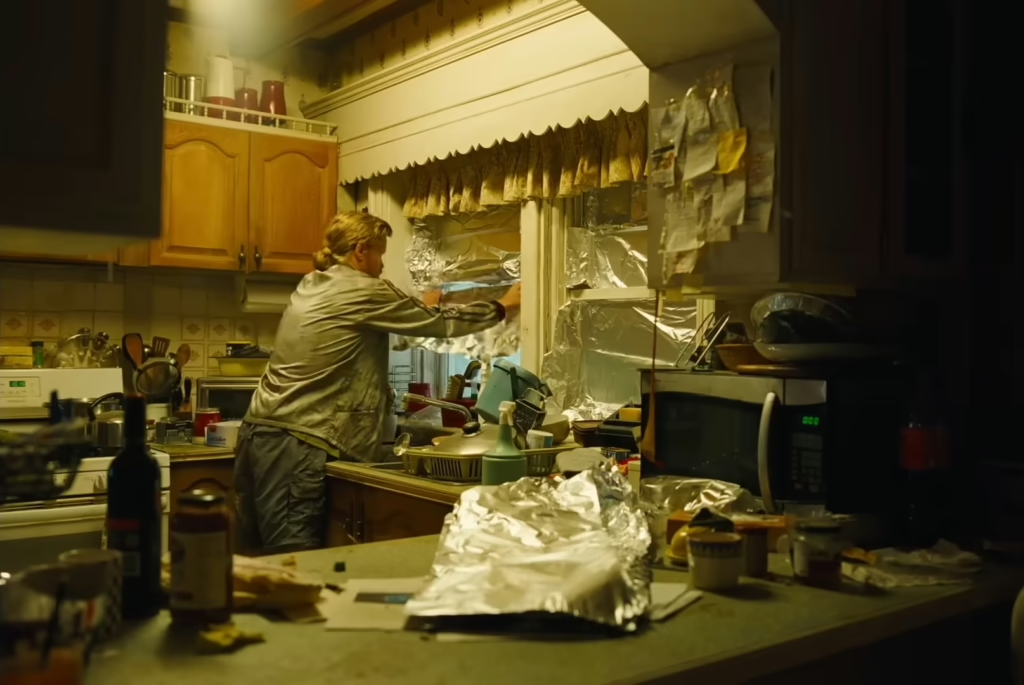

Indeed, it is tempting to believe that no real human is capable of the cruelty at the heart of corporate power, and the gaping divide between these characters appears worlds apart as Yorgos Lanthimos’ parallel editing contrasts Teddy’s messy rural home against Michelle’s sterile, shiny offices of glass and steel. Where Teddy tends to his bees with his intellectually disabled cousin Donnie, Michelle presides over a soulless empire of civil, bureaucratic coercion. Still, neither can entirely escape the misanthropic aspersions of Lanthimos’ cosmic joke, dooming capitalist titans and patchy-bearded zealots alike to their own self-inflicted ruin.

If there is any common ground shared by Teddy and Michelle, then it is their appreciation for honeybees, though even here their differences come to light. Where the executive admires their complex society and work ethic, Teddy condemns her praise as predatory, reducing nature’s harmony to a blueprint for exploitation. Auxolith is directly responsible for the Colony Collapse Disorder which has destroyed his hives, he claims, though her counter is effectively an indifferent shrug – perhaps it is merely time for the species to wind down. Through Lanthimos’ chilling, ecological metaphor, humanity thus becomes another colony in terminal decline, ignoring the countdown to their own extinction.

As the camera oscillates between wide-angle lenses and shallow-focus close-ups, Bugonia renders this clash with jarring precision, creating a visual whiplash that pulls us in and out of his characters’ orbits. Beyond the warped set designs of The Favourite and Poor Things, Lanthimos pushes his aesthetic towards austere, otherworldly minimalism, often following characters in rigid tracking shots and bathing in the sickly palette of Teddy’s dimly lit basement. The physical comedy is no doubt amplified by this formal rigour too, often observing Teddy and Michelle’s violent altercations in long shots that tangibly manifest the shambolic chaos of this deranged scheme.

When Bugonia plunges into Teddy’s monochrome memories distorted by unresolved trauma though, Lanthimos stretches the limits of his surrealism, rendering grief as a fever dream of giant needles, floating bodies, and devastating loss trivialised by corporate reparations. These sequences are stunning, though it is the film’s final movement which catapults its visual designs into delirious, uncanny spectacle, landing an existentially grotesque punchline. All the while, Jerskin Fendrix’s 90-piece orchestra erupts discordant strings and strained woodwinds into epic, apocalyptic grandeur, blending experimental textures with the thundering classical gravitas of Strauss and Wagner. The narratives stakes may often appear modest, yet this symphonic score inflates them to cataclysmic proportions, opening a musical window into Teddy’s operatic delusion.

Given the suffering that has long been inflicted on this obsessive conspiracy theorist too, it’s hard not to buy a little into his raw anger at those destructive, profit-driven institutions. Through his eyes, this corporate rot is the axis upon which the Earth’s fate tilts, fuelling an anxious fervour which quivers beneath Jesse Plemons’ impassive, deadpan restraint. Although his talent has been evident since the days of Breaking Bad, too often has he been confined to the margins of ensemble casts, thus making Bugonia the boldest showcase of his full comedic and dramatic arsenal yet. Ambiguous hints at childhood abuse further layer his fanaticism with a haunted vulnerability, but as this hardens into ritualistic brutality, no amount of trauma absolves him of horrors he inflicts.

Although Emma Stone has had no problem reinventing herself in recent years, Bugonia pushes her even further too, yielding an extraordinarily calculated performance. Gone is the flamboyant eccentricity of Bella Baxter in Poor Things, and in its place stands a cold, strategic ruthlessness, willing to indulge and manipulate whatever misguided beliefs may inch her closer to freedom. Her captors’ lack of education is just another vulnerability to exploit, and when she isn’t orchestrating outright harm, her corrosive influence seems to unintentionally wither everything it touches.

There are clearly no heroes or saviours in Lanthimos’ wry, cynical universe. Taking sizeable influence from the doomsday satire of Dr. Strangelove, Bugonia leaves us with a profound, existential unease, yet not without hope that the destruction we have wrought on the natural world might painfully give way to renewal. After all, in a pair of formally bookended shots, it is the bees that ultimately persist through the follies of humankind – as indifferent and implacable as Lanthimos’ own absurdist, cosmic irony.

Bugonia is currently playing in theatres.