Satyajit Ray | 2hr 2min

Death may be part of nature’s cycles, but that doesn’t make it any less of a disturbance to Apu’s childhood in Pather Panchali. Living in a rural Bengali village with his family and the elderly “Auntie” Indir, his days are spent wandering the forest, playing with his sister Durga, and watching live theatre whenever it rolls into town. It is as idyllic as a life in poverty can be, drifting by like a warm summer breeze that could only ever be interrupted by a cool, creeping change in the air. It is on one such day that Apu and Durga run through a waving field of white kash flowers to watch a train pass by, only to find Indir crouched in the forest, dying. Panicked, they run back into town to find some grownups, who carry her body away into the mist as a mournful, funereal hymn resonates in the background.

“Lord, the day is done and evening falls

Ferry me across to the other shore

They say you are the lord of the crossing

I call out to you.”

Feeble, demanding, and troublesome Indir may have been, but the humour she brought to the Roy household will certainly be missed by these children, who fondly clung to her mischief and stories. For Apu especially, it is the first major turning point in his young life, revealing the inevitable sorrow of a world that exists beyond his immediate reality. As he grows into adolescence and adulthood through Satyajit Ray’s Apu trilogy, grief will become a constant companion – though for now, it merely creeps around the periphery, hovering like a distant storm cloud on the horizon.

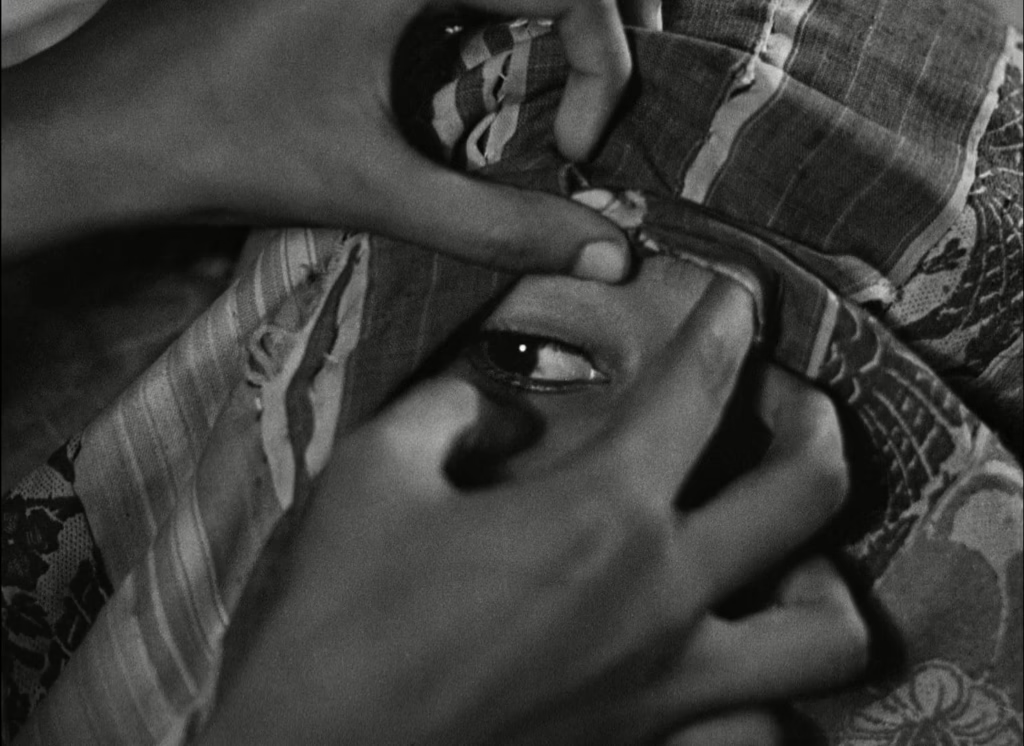

By and large, Pather Panchali is largely soaked in the bright innocence of childhood, with the six-year-old Apu’s introduction even resembling a figurative birth as he peeks one curious eye out from beneath a blanket and emerges into the world. Ray’s camera dwells on the mud houses, dusty yards, and wandering animals that betray the surrounding destitution, but none of this is for Apu and Durga to worry about. Responsibility for the family’s finances primarily sits with their father Harihar, whose employment as a priest earns little money and later forces him to find a new job in the city. His creative aspirations and guileless optimism do little to quell his wife Sarbajaya’s concerns as well, particularly when his extended work absence effectively leaves her to raise their son and daughter alone.

The Italian neorealist influence is evident in this small ensemble, contrasting the hardship of adults against the naivety of children, though Ray’s adoption of Vittorio de Sica’s cinematic ethos extends beyond theme alone. While Bollywood was flourishing in its 1950s Golden Age, dazzling audiences with extravagant romances and musical spectacle, Ray’s quiet corner of Indian cinema was exposing the authentic, unvarnished struggles of ordinary life through minimalist restraint and unembellished location shooting. The earthy, elemental textures of this village especially come alive through his observational lens, drawing out long takes that bask in the natural light, and framing scenes through tree branches and weathered archways.

By eschewing traditional narrative convention as well, Pather Panchali relishes the mundanity of daily existence, where one day fades into the next and time often unfolds without the structure of dialogue. Although the children stand at the centre of the film, both are largely passive characters, with Durga jealously watching her friend Ranu get married while Apu fixes his gaze upon whatever fleeting entertainment passes by. Where Durga does take a more active role is in her habit of stealing food from the neighbour’s orchard – ironic, given that this land was previously owned by her father but seized by relatives due to outstanding debts. When this girl is eventually accused of stealing a beaded necklace too, her mother’s loyal defence serves only to protect the family’s honour in public, before turning into a harsh rebuke behind closed doors.

As Apu watches his mother drag Durga by the hair, the sound of rattling drums replaces screams and yells, erupting in a visceral crescendo. Beyond rupturing the gentle peace of Apu’s world, these primal rhythms also pierce the film’s soundscape, otherwise defined by the ever-present sitar and bamboo flute that reverberate through the hazy village air. With virtuoso Ravi Shankar composing and performing the score, this music is rooted deeply in Indian classical traditions, often speaking for characters rather than merely embellishing the narrative. Especially for Apu, these breathy melodies and twanging harmonies evoke joy, sorrow, and confusion in the absence of words, accompanying the innocence that gradually seeps from young actor Subir Banerjee’s wide, expressive eyes.

So pervasive is the tactile, resonant score in Pather Panchali, it even seems to mirror the elemental forces at play, embodying a fluid transformation that becomes just as part of the landscape as the weather itself. From the ponds that capture Apu’s upside-down reflection to thundering monsoon rains, water plays a particularly vital role in Ray’s veneration of the natural world, often used as a bellwether for the family’s fortunes. When Harihar writes home about his recent financial success in the city, we watch dragonflies and water bugs form tiny ripples as they delicately skate across lakes. As tragedy begins to loom in the film’s final act though, a strikingly similar montage observes lily pads flap in the violent winds, and raindrops violently pelt the once-serene surface. While Apu shivers beneath a tree too, Durga basks in the heavy shower, before eventually joining him to pray.

“Rain, rain, away with thee.”

The storm does not let up throughout the following morning either when Durga falls sick, having caught a nasty cold. There is little that Sarbajaya can do to keep the harsh, outside world from penetrating the house as she cradles her daughter, its bitter winds extinguishing oil lamps, blowing open doors, and rocking a small icon of Ganesh. This is Ray’s most aggressive montage yet, though it is in the still, ruinous aftermath that we particularly feel its mournful impact. Drifting over the sodden debris and murky puddles, the camera eventually finds Sarbajaya holds Durga’s lifeless body, her eyes hollow with a grief too deep for tears.

In light of this calamity, Harihar’s oblivious, ill-timed return home cuts all the deeper. Proudly showing off his haul of goods from the city, he barely notices Sarbajaya’s sullen silence, until she finally releases the visceral pain that has welled up inside. Once again, Shankar’s impassioned score steps in to replace the sound of guttural cries, though this time introducing a new instrument – the tar shehnai. Its whining, piercing sound cuts through the air like a raw nerve, and as Harihar comes to the horrific realisation of their loss, the music also seems to mourn on his behalf.

For Apu too, Durga’s passing is a brutal initiation into a world of irreparable sorrow. Death is not just reserved for the elderly like Indir, but as we see in Pather Panchali’s formal mirroring of tragedy across generations, the youth are not spared either. The confusion in this child’s eyes fades to a disillusioned despair, echoing that of his parents who recognise what little is left for them in their ruined village. As they clear out their home to make a new life in the city, we also see just how deeply Apu has begun to grasp the value of remembrance, even at his young age. Uncovering the necklace that Durga previously stole, he decides to preserve her secret, tossing the jewellery into a pond so that it may never be found again. For Apu, this gesture thus becomes a private tribute, allowing him to carry forward a grief and love that acknowledges her enduring spirit.

Apu’s story would continue to unfold through the rest of Ray’s neorealist trilogy over the coming years, though with his diminished family’s sombre departure, it is apparent that this will be the last time he ever lay eyes upon the village of his childhood. Still, even in the absence of humans, nature continues to stir, reclaiming their now-abandoned home as a snake winds its way through the rubble and slips quietly inside. Apu may grow, mourn, and leave the sunny days of his youth behind in Pather Panchali, yet the sacred cycles of Ray’s world persist, holding memories of innocence and sorrow within its sacred, primordial pulse.

Pather Panchali is currently streaming on The Criterion Channel, and is available to rent or buy on Apple TV.