Eva Victor | 1hr 44min

Ever since “The Year with the Bad Thing”, Agnes’ life has been divided up into chapters. For this New England literary professor, it is a method of marking milestones as she works through the resulting trauma, though from our non-linear perspective it keeps that “bad thing” painfully present in the foreground. Even before we understand what this may be, its shadow hangs heavy over the “The Year with the Baby”, which is simultaneously our first chapter and the last in her chronological timeline. Living by herself on the edge of the woods, she is visited by newly pregnant college friend Lydie, whose warm presence is only outdone by her emotional intuition. Her concerns over Agnes’ mental health are certainly warranted, though this lonely academic’s dark sense of humour also incidentally reveals her own mechanisms to deal with the unspoken sorrow.

“If I was going to kill myself, I would have done it last year.”

Eva Victor is not a commonly recognised name in the cinephile community, but in time, it very well may be. Sorry, Baby certainly features a strong ensemble cast including Naomi Ackie, Lucas Hedges, and a particularly disarming cameo from John Carroll Lynch, but as the star, writer, and director, this is primarily Victor’s passion project. Armed with a sharp wit and dry sardonicism, the first-time filmmaker skilfully keys into the quirks and foibles of modern friendships – receding with distance, yet always reliable, returning as cyclically as the trauma they seek to soften.

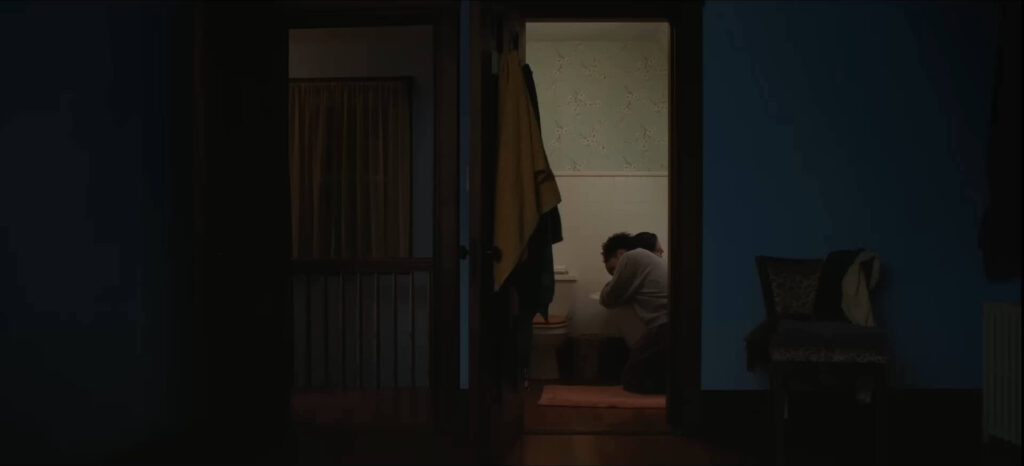

It is this close bond between Agnes and Lydie which dominates the first 20 minutes of the film after all, dwelling calmly in Agnes’ beautiful, rural home. Handsome coastal landscapes, candlelit dinners, and a soothing score of vocals and piano accompany their tender reunion, unfolding not through plot or conflict, but rather in the melancholy foreshadowing of their affectionate interactions. The setup is necessary for the following flashback, revealing Agnes’ life several years ago as a young graduate working under professor Preston Decker, whose genial mentorship masks a more insidious entitlement. Friendly meetings in his office eventually lead to an encounter at his home, though we notably do not join them inside. As we sit in a wide shot across the street, jump cuts mark the passage of time, before Agnes eventually emerges in stunned silence. Long takes follow her as she walks and drives in numb silence, only speaking for the first time when she finally reaches Lydie’s place.

“My pants are broken.”

Victor continues to hold the camera on her face as she recounts the sexual assault in discomforting detail, simultaneously exposing the raw vulnerability beneath her practiced wit. If there is anyone to share the emotional load though, it’s Lydie, confronting the callous doctor when she’s examined for forensic evidence and unquestioningly accepting her sudden adoption of a stray kitten.

“Whatever you need.”

Nevertheless, the closure Agnes seeks is almost immediately denied by Preston’s hasty resignation and disappearance. The college disciplinary board offers weak sympathy, assuring her they know what she is going through because “We are women,” and although her promotion to full-time professor offers a semblance of progress, she can’t quite shake the uneasy feeling of occupying her rapist’s office.

The years that pass in the wake of her trauma are not given quite as much weight in this fragmented narrative structure, yet their seemingly trivial titles speak sincerely to the personal landmarks of her recovery. “The Year with the Questions” revolves solely around the jury selection process for a court case she has been called to serve on, and the prosecutor’s probing of whether her experience as a victim of crime compromises her impartiality. “The Year with the Good Sandwich” meanwhile offers a chance run-in with a hospitable sandwich shop owner, calming an unexpected panic attack and offering a grounding, fatherly presence. Lydie’s move away from home may leave Agnes more isolated than ever, and a seemingly haunted door hangs an unacknowledged disquiet in the air, yet persistent hope remains in the steady companionship of Olga the cat.

Tied up in Victor’s character study as well are notions of Agnes’ evolving attitude towards gender and sexuality. Nothing seems to be as clearcut as it was before, reflecting Victor’s own non-binary identity as she ticks ‘Female’ on a form, and amusingly draws a two-way arrow to the ‘Male’ box. As she grows more confident in her scholarly career too, she adopts more masculine-coded clothing, and even challenges the sexual trauma narrative in her unexpected appreciation for Vladimir Nabokov’s controversial novel, Lolita. The formal qualities of this literary art prompt deeper engagement with its harrowing content, she emphasises to her class, effectively reclaiming this infamous story of an abusive academic.

The tonal balance that Victor strikes in this mix of tragedy and sharp humour may be their greatest achievement in Sorry, Baby, though it is a note of poignant reflection which ultimately ends our journey with Agnes. Returning to “The Year with the Baby”, she is once again visited by Lydie, though this time with her wife and newborn in tow. It’s not exactly maternal instinct that surfaces when she’s left alone with Jane, but something more tentative and personal, expressed through the words she wishes someone might have said to her when she first entered this world.

“I’m sorry that bad things are going to happen to you. I hope they don’t. If I can’t ever stop something from being bad, let me know. But, sometimes, bad stuff just happens. That’s why I feel bad for you in a way. That you’re alive, and you don’t know that yet.”

Still, if there is anything that can stave off the darkness, it is the simple grace of being witnessed.

“I can still listen and not be scared. So that’s good. Or that’s something, at least.”

It is a touching monologue which ends the film, and one which places Agnes’ own ongoing process of healing within the span of an entire life. “The bad thing” might be different for Jane as it is for everyone, and may often even be inevitable – yet perhaps, according to Victor’s nurturing worldview, it can at least be softened. Whether through a friend, a cat, or a benevolent stranger, companionship offers resistance in Sorry, Baby, affirming survival as a shared, ongoing act of connection.

Sorry, Baby is coming soon to VOD.