Gus Van Sant | 1hr 21min

The few minutes of peace before shooters Eric and Alex unleash horrendous violence upon their school are extraordinarily unremarkable, yet Gus Van Sant returns to this moment exactly three times in Elephant. On first pass, we are attached to John – a sensitive but lonely student whose peers are nevertheless fond of him. Walking through the empty school hallways, he greets student photographer Elias, who takes a moment to chat and snap his picture. As John continues outside, Eric and Alex come into focus carrying black bags. “Just get the fuck out of here and don’t come back. Some heavy shit’s going down,” they warn, giving him just enough time to escape.

The second time this scene plays out, it is Elias who the rolling camera latches onto. Emerging from the school’s darkroom, he is silhouetted by a bright corridor ahead, where we are about to watch the same interaction unfold from the opposite angle. For both students, it is a pleasant but brief exchange that might have faded into the miasma of an otherwise ordinary day, were it not for the carnage soon to unfold in the library where Elias is heading.

Michelle’s presence in this scene is so fleeting, she is initially rendered a blur running past in the background, yet it is her perspective we are given the third and final time Van Sant revisits this encounter. She is another outcast at this school, her body image painfully brought to the forefront when the gym teacher requests that she wears shorts instead of pants, and in the locker room where girls giggle about her “granny panties.” She also earns the shallowest depth of field of all the characters, effectively living in her own self-contained silo – so the fact that she too should be in the library when Eric and Alex commence their shooting spree seems a tragic convergence. “Hey, you guys…” she begins when she hears their guns cock, but as their first victim, whatever words she intends to follow are tragically silenced.

Van Sant does not strive to make sense of such senseless brutality in Elephant, and although its loose basis in the Columbine High School massacre is clear, he avoids offering any reductive diagnosis. Instead, his camera observes without commentary, stalking characters from behind and lingering on the back of their heads when it moves into close-up. We occupy a space just beyond their periphery, yet due to the sheer persistence and duration of these long takes, we develop a strange, one-sided bond with them. We know that popular girls Brittany, Jordan, and Nicole resent Carrie for dating handsome jock Nathan, and we know that they routinely purge their lunches in the bathroom before class. We understand that Acadia is not only a member of the gay-straight alliance, but also a genuinely caring classmate, comforting John who privately struggles with his alcoholic father. Across this ensemble of non-professional actors, dialogue is largely improvised, organically shaping each character and delivering authentic, non-judgemental reflections of adolescence in all its awkward forms.

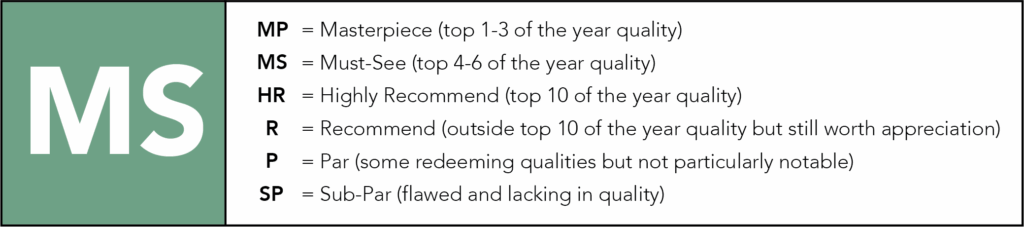

If there is anyone here who we fail to properly grasp, then it is the killers themselves, whose motivations escape the simplistic explanations so often applied to school shooters. Alex is clearly mentally unwell and takes advantage of Eric’s passiveness, though beyond that, Van Sant teases all sorts of influences without pointing to any single one. In Alex’s spare time, he plays violent video games and watches documentaries on Nazi propaganda, while in the classroom he is the victim of targeted bullying. The ease with which he orders a firearm online and has it delivered to his front door is disturbing as well, and it certainly doesn’t help that these boys totally lack adult guidance in either home or school environments.

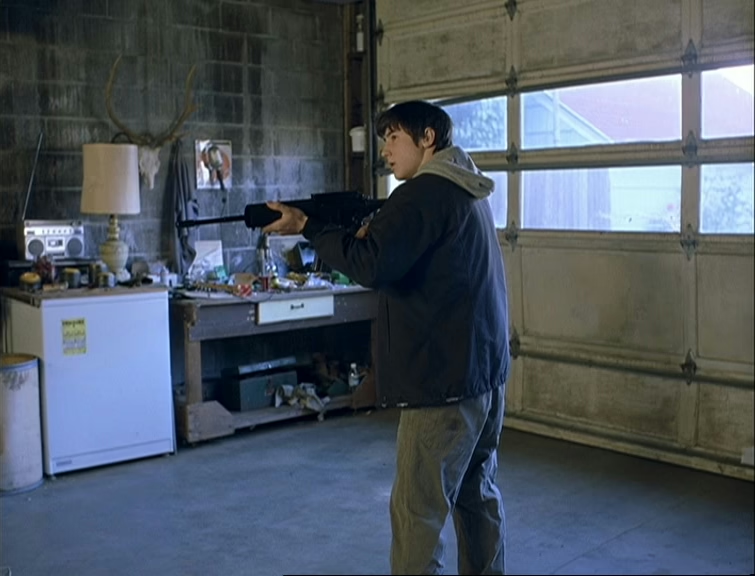

Most curiously of all though, there is a tension between sensitive expression and repression within Alex’s character that emerges through his musical talent, ominously appropriating classical pieces into unsettling, recurring themes. Amid an otherwise stark soundscape, these melancholy motifs carry a chilling emotional texture, as if speaking for Alex in the absence of dialogue. The kiss that he and Eric share in the shower right before they commit the shooting only further complicates our understanding of their psyches, prompting speculation around their closeted homosexuality. As a result, Van Sant’s focus on the school’s queer-straight alliance becomes more nuanced – despite the opportunity for community and acceptance among their peers, still these boys bitterly stand on the outside looking in.

Although much of the film takes place over a single day, the sequence of Alex and Eric’s flashbacks is much vaguer, as if to place them in a timeless, existential limbo. Van Sant eschews timecodes that might pinpoint the chronology of the shooting too, instead building his structure on each character’s perspectives, introduced through title cards bearing their names. The result is formally audacious, seamless melding his complex narrative architecture with tracking shots that move with languid insistence, and dwell in the mundanity of school life.

Though we catch glimpses of the massacre earlier in Elephant, it isn’t until the final stretch that we follow it from Eric and Alex’s point-of-view, where Van Sant uneasily intercuts the casual discussion of their plan with its brutal execution. Gazing up at a turquoise sky, the camera watches clouds drift by as thunder rumbles in the distance, underscoring the eerie calm before the storm – and when that violence does finally unfold, the time we have spent meeting each character renders their fates all the more devastating. After Michelle and Elias are the first to perish in the library, Brittany, Jordan, and Nicole are targeted next in the girl’s bathroom, while Nathan and Carrie unwisely brush off the distant gunshots as some passing commotion. At the very least, we are mercifully assured of John’s safety, as he attempts to raise the alarm outside the school after Alex’s unnerving tipoff.

Quite unexpectedly, it is here where Van Sant introduces one final character, very late in the film. Tall and muscular, Benny fits the mould of the classical hero, stepping in to help a petrified Acadia climb out a classroom window. Despite his confidence though, it would be foolish to believe that he will somehow become the school’s saviour. As Eric holds a teacher at gunpoint in a corridor, Benny calmly approaches from behind to save another life – only to be abruptly executed with a shot to the chest. As Van Sant so harshly reminds us, there are no heroes in Elephant.

Indeed, violence arrives without warning, logic, or resolution in this vision of terrifying randomness, and finds its most haunting expression in the final scene. As Eric proudly lists his kills, Alex cuts him off mid-sentence with a bullet, delivered with the same unceremonious callousness as every other victim. Whether it is a final gesture of mercy or a cold act of betrayal, Van Sant leaves us answerless, similarly suspending the fates of Nathan and Carrie in agonising uncertainty when Alex discovers their hiding spot. He has no specific vendetta to fulfil here – whoever he kills first is to be decided by a game of ‘Eeny, meeny, miny, moe’, lingering in the air as the camera quietly rolls away, and leaving the outcome to unfold offscreen. The mournful aftermath of Elephant’s inhuman tragedy is not something that these students will ever bear witness to, and with Van Sant’s final, ambiguous retreat into silence, neither shall we.

Elephant is currently streaming on HBO Max.