Yasujirō Ozu | 2hr 8min

On some level, both Akiko and her 24-year-old daughter Ayako long to marry and settle down in Late Autumn. Seven years have passed since the loss of their dear husband and father Miwa, now commemorated by a memorial service attended by his three college friends Mamiya, Taguchi, and Hirayama, and setting the stage for new matrimonial possibilities. As such, this trio of matchmakers takes it on themselves to ensure Miwa’s surviving family is provided stability, only to find both mother and daughter locked in a stubborn stalemate – neither willing to pursue marriage if it means leaving the other behind.

This is not the first time that Yasujirō Ozu would revisit a story from earlier in his career. Late Spring similarly examined one young woman’s resistance to stepping away from her family and becoming a wife, though the relationship dynamics in Late Autumn are crucially different, replacing the widowed father with a mother and positioning her at a similar crossroads. That Setsuko Hara should play the older counterpart of her role in Late Spring only underscores the steady passage of time that inevitably takes hold of every Ozu film, observing each generation recede as the next rises, and here evolving the nurtured child into the protective guardian.

Even more notably, Ozu’s recent shift to colour filmmaking distinguishes Late Autumn’s vibrant visual palette, weaving organic green hues through office interiors, commercial signage, and mountainous pillow shots. This does not automatically render it a superior film to the black-and-white minimalism of Late Spring, but its vibrancy is nonetheless infused with a strong undertone of growth and renewal, often offset by bursts of contrasting hues. Right in the very first shot, the red beams of Tokyo Tower are obscured by foliage from a low angle, while later the Westernised independence of Ayako’s friend Yuriko is loudly announced through her purple knit sweater. Overshadowed it may be compared to Ozu’s masterpieces of this period, but Late Autumn’s updated examination of shifting Japanese traditions still finds fresh emotional textures in its colour compositions.

By extending his aesthetic patterns to Akiko and Ayako’s blocking too, Ozu visually illustrates the parallels between both characters, mirroring their poses and costuming like twins. These two women equally consider the prospect of marriage, yet their narrative arcs diverge in what it represents at their respective ages, nudging one towards motherhood while the other seeks to reclaim the love and security she shared with her late husband. For young Ayako at least, there is the additional concern of what exactly happens to one’s relationships when marriage shifts the balance of everyday life, stoked by the growing distance she senses with one of her own colleagues. As she and Yuriko watch the train carrying their newlywed friend pass by, they’re quietly disappointed when she doesn’t wave her bouquet from the window as promised, effectively establishing this railway shot as a recurring symbol of emotional departure in Ayako’s life.

As well-meaning as our three mischievous matchmakers may be, even setting up Ayako with a young man named Goto, they don’t exactly help the situation with their behind-the-scenes plotting. Realising that she has no intention of marrying Goto and letting her mother live alone, they commence the second part of their plan, facilitating a romance between Akiko and Hirayama. It is when Mamiya unwisely lets the scheme slip to Ayako though that tensions ignite, inadvertently leading this young woman to believe her mother has been keeping secrets. “It’s an affront to Father’s memory,” she protests to a bewildered Akiko, barely letting her get a word out before storming off.

In the thick of emotional turmoil and confusion, it is Yuriko who provides the sole voice of reason. “You have someone you like. Why can’t she?” she asks, encouraging a shift in perspective that comes with modern society’s loosening grip on the past. She was fine when her own father remarried, she points out, and she still hasn’t forgotten her mother. To help further smooth over the creases though, she also visits Akiko to clear up the misunderstanding, assuring her that Ayako will be fine if she truly wishes to remarry. As the final stop on her mediation tour, she invites the three men to her family’s restaurant for a light scolding, and to better understand Hirayama’s intentions.

There is a warm levity in this sudden reversal of power dynamics, giving Yuriko the home ground advantage as she gracefully commands the room and amusingly outdrinks her guests. Humour is an integral part of Ozu’s domestic dramas, counterbalancing the momentous narrative stakes, and especially working here to put the hapless men in place. Perhaps even more significantly, it also offers the false impression that a purely happy ending is in store, inviting us to join Akiko and Ayako’s final family getaway with a hopeful sense of closure.

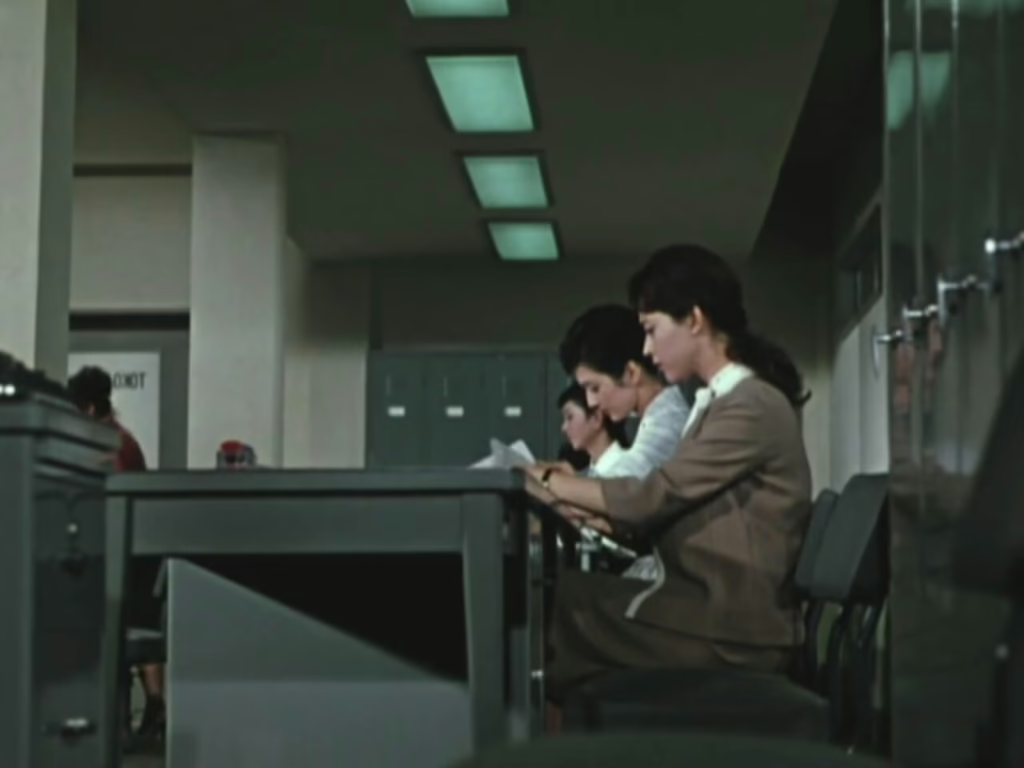

The story of their stay at the Tawaraya Inn is effectively captured in the three establishing shots set outside, the first of which reveals a bustling, lively nightlife. Inside, spirits are similarly high, right up until Akiko comes forward with the truth. “Your father was enough for me. He’ll always be by my side,” she explains to a shocked Ayako, revealing her decision to remain a widow. As her daughter breaks down in tears of guilt, Ozu returns to the exterior shot for second time, now dark and subdued with the settling night.

As with life and all Ozu’s films though, morning arrives to ease the sorrow. For one final time, right before we join this family at breakfast, we revisit that recurring long shot now bathed in the soft light of dawn. “You’re beginning a new life, and so am I,” Akiko reassures her daughter as a class of children sing in the background, marking this moment of transition with their own lyrical reflection on changing seasons.

“Autumn leaves in every hue

Of yellow and red

Float down the stream

Woven like brocade.”

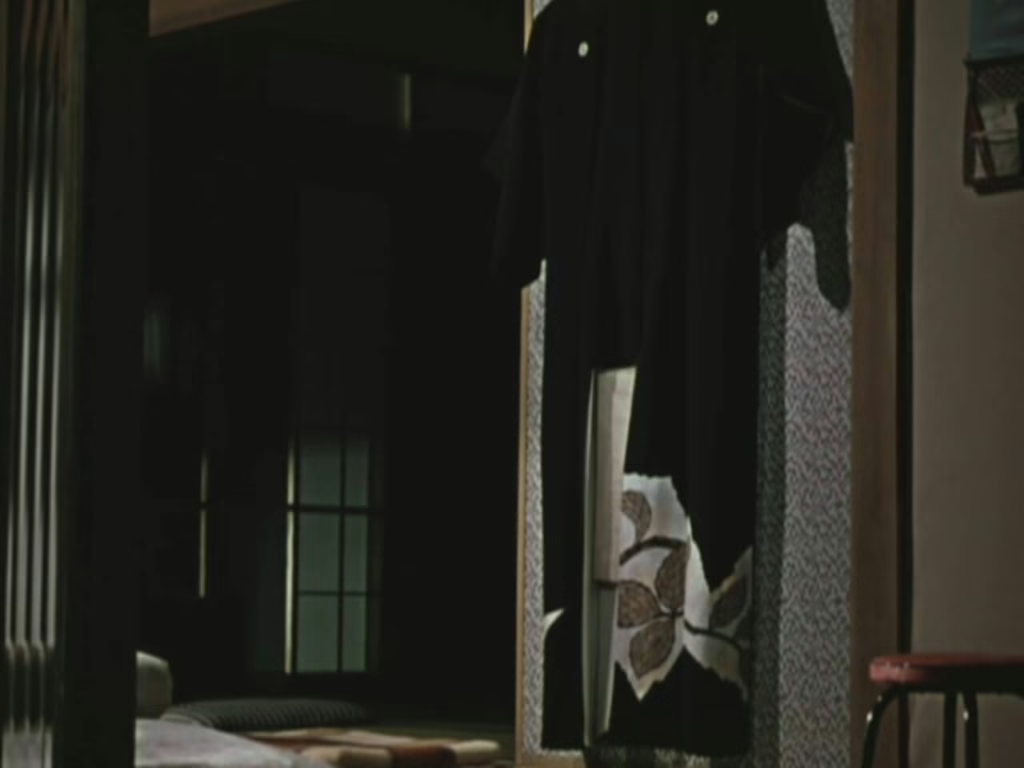

That Ayako virtually disappears from Late Autumn the moment her wedding is over only deepens the sorrow left in her wake. Her absence is felt, not just in the stillness of the house, but most tangibly in that untouched, hanging robe which draws her lonely mother’s gaze. Where Chishū Ryū earned the final moment in Late Spring through his poignant peeling of an apple, Hara owns it here with a wistful, bittersweet smile, embracing her enduring solitude and the grace with which she chooses to carry it. We are no witness to whatever new beginning Ayako might be stepping into – only to the quiet dignity and strength of a mother left behind, learning to let go.

Late Autumn is currently streaming on The Criterion Channel