“Although I may seem the same to other people, to me each thing I produce is a new expression and I always make each work from a new interest. It’s like a painter who always paints same rose.”

Yasujirō Ozu

Top 10 Ranking

| Film | Year |

| 1. Tokyo Story | 1953 |

| 2. The End of Summer | 1961 |

| 3. Early Summer | 1951 |

| 4. Late Spring | 1949 |

| 5. Floating Weeds | 1959 |

| 6. A Hen in the Wind | 1948 |

| 7. An Autumn Afternoon | 1962 |

| 8. The Only Son | 1936 |

| 9. There Was a Father | 1942 |

| 10. A Story of Floating Weeds | 1934 |

Best Film – Tokyo Story

At the height of Yasujirō Ozu’s powers, he directed one of the most visually immaculate films ever made, capturing all his greatest stylistic devices in an intricate, elegiac reflection on family duty and cultural transition. First and foremost, the compositions are unparalleled wherever you look in the history of cinema, arranged with a geometric precision that defines the rigorous lives of the Hiryama family. Through staggered blocking, pillow shots, and low tatami angles as well, Ozu cultivates contemplative rhythms that elevate domestic routine to poetic transcendence, stripped of obtrusive distractions. While grandparents Shūkichi and Tomi cling to traditional values, their children and grandchildren pursue a more independent future, and Ozu binds all three generations together through the meditative routines of everyday life. As the centrepiece of this narrative, the Hiryama family embodies a delicate microcosm of post-war Japanese culture, though it is Ozu’s exacting formal craftsmanship which grants Tokyo Story such a timeless, resonant grace.

Most Overrated – I Was Born, But…

The TSPDT consensus ranks this examination of childhood, class, and authority as the 379th best film of all time, and Ozu’s 4th best – about fifteen places too high in his filmography. The meticulous framing that would define his later work is still in its infancy here, not yet perfecting his art of geometric interior compositions. Even so, I Was Born, But… demonstrates a keen sense of spatial economy, finding endearing synchronicity between the two young boys at the centre, and mirroring their social struggles in their father’s own parallel story arc.

Most Underrated – The End of Summer

This is not the 913th best film of all time, as the TSPDT consensus insists, and neither is it a mere footnote in Ozu’s filmography. In terms of pure visual storytelling, The End of Summer‘s family drama competes with only a handful of his greatest works, harnessing the subtle power of colour cinematography to evolve his geometrically precise style. Ageing patriarch Manbei is one of his most entertaining characters, and in the family sake brewery, we find the strongest symbol of his personality and power – whether it is flourishing through pillow shots of barrels or dwindling with the threat of acquisition. Humour and tragedy seamlessly co-exist in this meditation on marriage, driving the film towards a poignant, mesmerising conclusion.

Gem to Spotlight – Equinox Flower

Ozu directed six films in colour, and right from his foray into this new style of filmmaking, he demonstrates an immediate affinity with bold, primary palettes and vibrant compositions. These align beautifully with Equinox Flower‘s eloquent optimism too, radiating the warmer end of the colour spectrum through assorted pieces of décor, costuming, and that bright, crimson kettle which finds its way into almost every interior shot. Ozu’s story of a father’s reluctance to let his daughter marry eventually resolves with tender acceptance of the younger generation’s independence, recognising that even the most rigid traditions can bend towards love.

Key Collaborator – Kōgo Noda

As with many prolific directors, Ozu worked with numerous collaborators, each essential in their own right. With cinematographer Yūharu Atsuta’s expertise, Yasujirō Ozu developed his meticulous visual compositions, while editor Yoshiyasu Hamamura helped refine his distinctive formal rhythms. Chishū Ryū and Setsuko Hara also became fixtures of his casts, emerging as two of Japan’s greatest actors, yet his partnership with co-writer Kōgo Noda is the only one to span Ozu’s entire career, providing his narrative foundations.

Together, their screenplays thoughtfully consider the nuances in loving yet strained family dynamics, and their reflections of Japanese society at large. Noda’s writing provides precise, emotionally resonant narratives that leave space for Ozu’s cinematic expression, allowing everyday moments to carry profound emotional weight. Noda structured the stories, while Ozu shaped their rhythm and atmosphere, innovating the formally rigorous artistry they are celebrated for.

Key Influence – Ernst Lubitsch

Yasujirō Ozu’s style is so dissimilar to any other that came before him, this category is almost impossible to pin down, yet his explicit admiration of Ernst Lubitsch nevertheless reveals the unexpected impact of early Hollywood on his work. This manifested in his silent comedies, and in Woman of Tokyo, his characters even watch the Lubitsch film If I Had a Million at the theatre. As his storytelling matured into domestic dramas, still he maintained a light sense of humour – sliding open a door to reveal an eavesdropping husband in Early Summer, for instance, or the elderly Manbei trying to shake his employee’s tail on the way to his mistress’ house in The End of Summer.

The famed ‘Lubitsch touch’ was all about suggestion, and consequently goes hand in hand with Ozu’s narrative ellipses, withholding key events to let the audience piece the story together themselves. Good Morning may ultimately be the film that comes closest in spirit to Lubitsch’s comedy, blending high and lowbrow humour to great effect, and even adding a twist to his laundry shot – playfully implying that the pants we see hanging on the line have been soiled.

Cultural Context and Artistic Innovations

Silent Apprenticeship (1927-35)

Beginning his career in the cinematography department of Shochiku Film Company, Yasujirō Ozu quickly worked his way up, and by 1927 found himself in the director’s chair. As is the case with so many silent films, his earliest works are unfortunately lost, but many of those which did survive are not especially notable. During this period, he plays around in crime, comedy, and romance genres, though it is only when he moves towards drama in Tokyo Chorus that he begins to find greater artistic success. Here, he expresses extraordinary reverence for teachers, and from this point on frequently depicts them as father figures to their students.

Ozu’s recurring fascination with Tokyo begins early, referenced in the titles Tokyo Chorus, Woman of Tokyo, and An Inn in Tokyo, and later on in Tokyo Story and Tokyo Twilight. These films chart the city’s evolution across decades, each time using Tokyo less as a setting than as a shorthand for modernity. Here, tradition is acutely tested, and the fractures of contemporary life poignantly emerge.

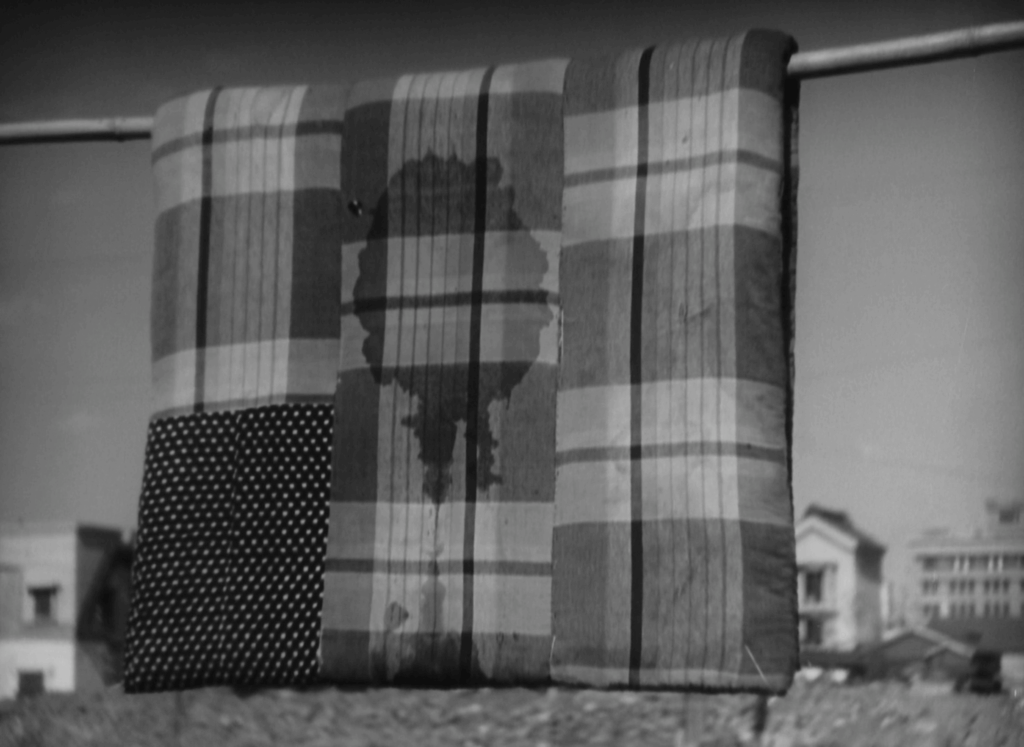

Japanese cinema in general was slower to adapt synchronised sound technology than Hollywood, giving Ozu the unique opportunity to experiment with silent storytelling well into the 1930s and develop his own techniques along the way. Though not yet fully formed, his trademark pillow shots emerge early, used as scene transitions that lift us outside the narrative flow and slip through elegiac clusters of wide shots. Time seems to dissolve together in these measured montages, yet we are always firmly rooted in a sense of location, passing through village streets and carefully set interiors. Domestic objects such as kettles also suggest the subtle persistence of human activity in otherwise empty shots, while his trademark cutaways to hanging laundry imprint human cut-outs onto his scenery, effectively representing characters through the mundane artefacts of their existence.

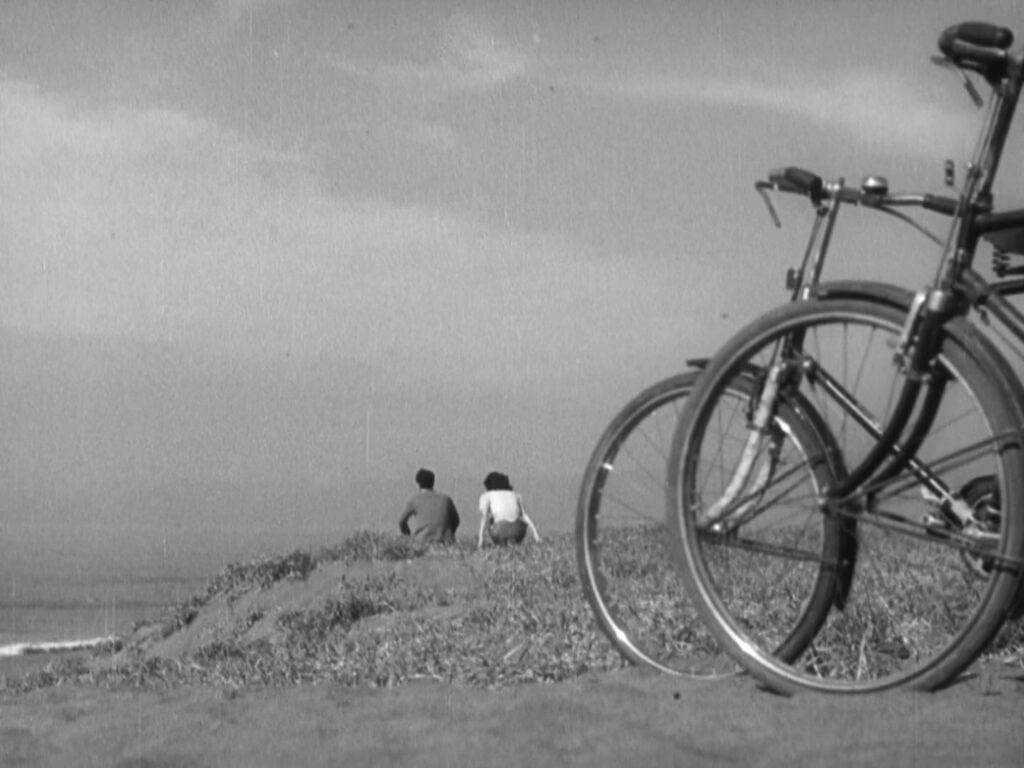

Ozu’s tatami shots also begin here, elevated a few feet off the ground and mimicking the low angle viewpoint of a person sitting on a traditional Japanese tatami mat. Paired with his proclivity towards 50mm lenses which replicates regular human vision, it often maintains a passive, observational perspective. In I Was Born, But… however, we see how it is used to match the eye level of the child protagonists, empathising with them over the adults in their lives.

It was a slow ascent to greatness for Ozu, spending several years refining his craft through working class narratives, until A Story of Floating Weeds came along as evidence of his enormous potential. Here, lyrical melodrama is blended with touches of humour, and his carefully constructed cinematic language gives shape to the dramatic tension between travelling actors and village locals. There is an elegance to his depictions of poverty, never romanticising it, but rather alternating between sparse minimalism and lived-in clutter to render aesthetically striking compositions. Like many of Ozu’s films, honour and tradition are placed at the forefront of the characters’ relationships, breeding shame and driving families apart through perceptions of class status.

Social Reckonings (1936-48)

The Only Son is Yasujirō Ozu’s first sound film, marking an unusually effortless transition that many other directors of the period struggled to match. His cynicism becomes readily apparent as he starts addressing social issues head on, using the economic hardships of the Great Depression as the backdrop to a story of parental expectations and disappointments. The prospect of education elevating class or status seems increasingly unlikely here, leaving characters to grapple with dreams that no longer match the world they inhabit.

Ozu’s conscription into the Imperial Japanese Army brought a brief halt to his filmmaking career, and although he wrote the first script draft of The Flavor of Green Tea Over Rice during this time, he temporarily shelved it due to military censorship. Instead, the first film he directed upon his return was The Brothers and Sisters of the Toda Family, turning his critical lens to Japan’s upper-class. Families remained the focus of his narratives in this period, but generations gaps between parents and children continued to widen, exposing a mismatch in traditional and modern values.

When World War II came to an end, Ozu did not wait to begin reflecting on its social impact. Record of a Tenement Gentleman expresses incredible empathy for children displaced by its devastation, often orphaned or abandoned, while A Hen in the Wind examines the difficult decisions one mother must make due to economic hardship. His path may have never crossed with the Italian neorealists of the time, but his ability to find tenderness and tragedy in the mundane rhythms of everyday life certainly aligns with theirs, affected by a similar post-war disillusionment.

Formally too, Ozu continues refining his visual storytelling, echoing larger tragedies in the details of his mise-en-scène. In A Hen in the Wind, he represents characters through common items, following the trajectory of a can as it is thrown downstairs and foreshadowing our protagonist’s tumble later on. In There Was a Father, a string of pillow shots similarly introduce a class of students through their perfectly aligned umbrellas, and later reveals one toppling over when a child tragically drowns.

On a purely aesthetic level, he begins cultivating a harmony in his visual patterns here too, notably drawing parallels between parent and child in There Was a Father through the simple motion of fishing lines cast in unison – incidentally calling back to a similar shot from A Story of Floating Weeds. Within this framework, he resists dynamism, favouring static tableaux where figures sit frontally and only the smallest gestures punctuate the calm equilibrium.

Pillow shots also become their own form of cinematic punctuation in this period, using cutaways to bookend scenes with familiar visual elements, step away mid-scene to sit with a particularly intense emotion, or symbolically develop a recurring motif. In these landscapes, meticulous visual order is imposed through railings, bridges, and telephone poles that partition the scenery into neat compartments. His shots of hanging laundry in these montages are visually evolving too, functioning not just as carefully structured elements within the frame, but at times even conveying pieces of narrative information.

Mature Masterpieces (1949-62)

By 1949, Ozu had perfected his craft, beginning the four-year period which officially marked his artistic peak with a trio of masterpieces – Late Spring, Early Summer, and the unassailable Tokyo Story. Together, these form the Noriko trilogy, each centring Setsuko Hara as a different women named Noriko and exploring the various roles that women played in post-war Japan. He eschews any remaining traces of melodrama here, allowing his subdued contemplations of domestic obligation and shifting family structures to step fully into focus.

More trends also emerge in Ozu’s film titles, frequently reflecting times of the year (Late Spring), times of the day (Good Morning), nature (Floating Weeds), or some combination of each (An Autumn Afternoon, Equinox Flower). The imagery he evokes is deeply elemental, touching on every season except winter – perhaps due to its associations with death rather than life. Even more significantly, these titles suggest cycles of renewal and ageing, mirroring Ozu’s characters as they move through marriages, funerals, and rituals of generational handover.

With regular collaborators like Setsuko Hara and Chishū Ryū still present too, we even see them age into the older counterparts of their previous roles, underscoring the steady passage of time that inevitably takes hold of these characters. Ozu likewise takes the chance to revisit his earlier stories, remaking A Story of Floating Weeds in colour, echoing the comedic childhood rebellion of I Was Born, But… in Good Morning, and developing Late Spring’s story of a daughter leaving home to marry in Late Autumn and An Autumn Afternoon.

Ozu partly recognises generational clash as a natural part of a family’s life cycle, yet against the backdrop of post-war Japan, he also uses it to illustrate shifting cultural values. Grown children no longer have time for their ageing parents, and often outright reject Japanese tradition, hoping to move forward from its burdens. This is a new, rejuvenated nation striving towards a more hopeful future, yet its unstable foundations also lead to the dispassionate breakdown of marriages, taking centre-stage in The Flavor of Green Tea Over Rice and Early Spring. In their eagerness to adopt Western aspirations, many turn away from the conventions that once held families together, and these fractures are only exacerbated by the lingering trauma of war. Young widows grieve their late husbands, old army buddies reminisce over drinks, and some even outright mock that old-fashioned nationalism which led their country to ruin.

Although tradition fades in this changing culture, remnants of Japan’s proud history survive through diegetic songs, musically painting reflections on memory, nature, and change. Ozu aligns his own films with that lineage of Zen-inflected art as well, evoking a sense of ‘mono no aware’ – a Japanese idiom which expresses poignant awareness of life’s transience, yet also an acceptance of it as the natural order of all things.

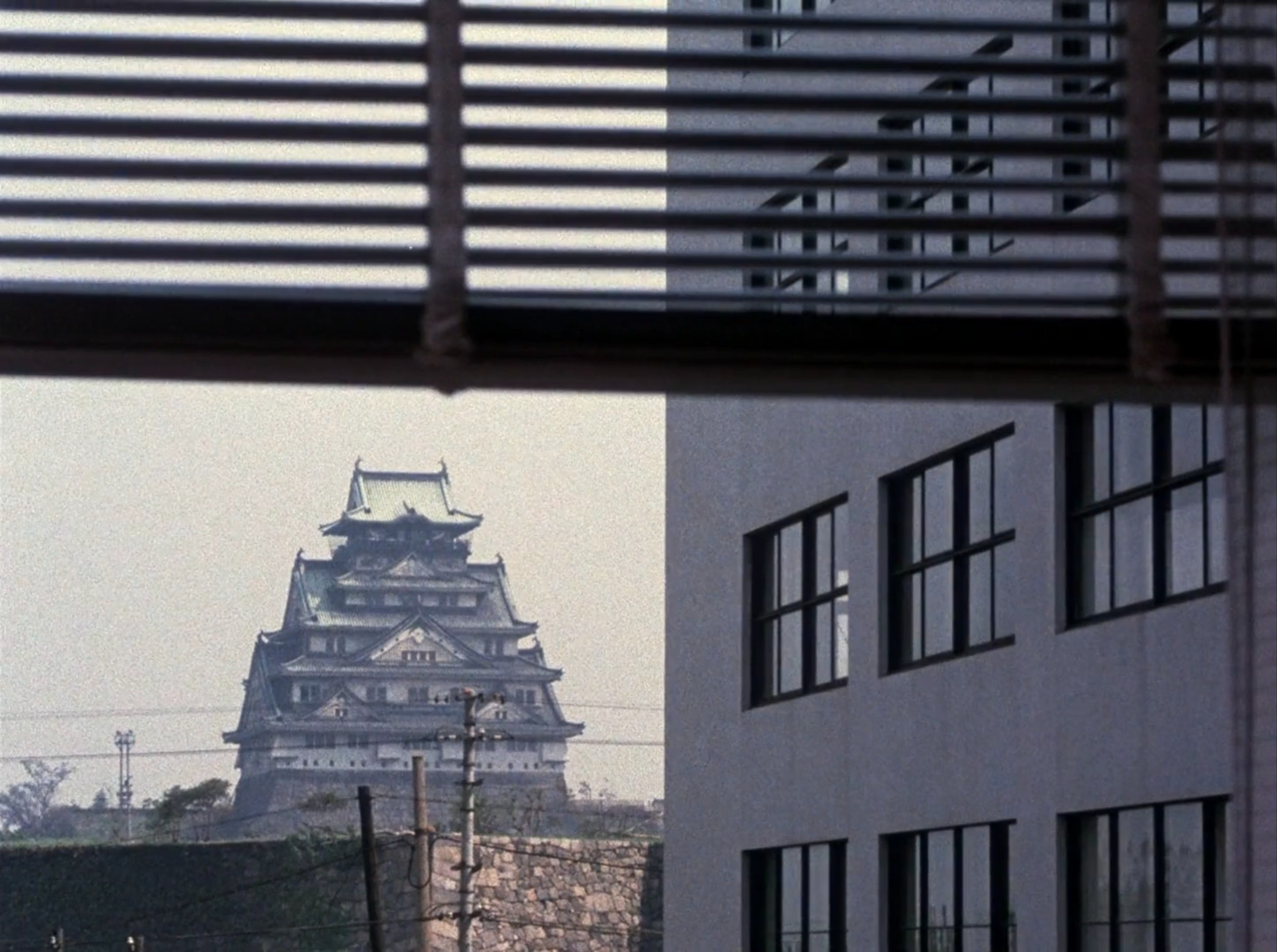

This transcends mere theme and is woven into the formal fabric of his films, taking the time to move beyond the immediate narrative and convey the broader cultural context through pillow shots. There, historic temples and modern infrastructure often inhabit shared spaces, embodying character tensions between tradition and modernity on a larger scale. While these languid montages seem to dissolve time altogether as narrative bookends and scene transitions, the dutiful repetition of specific shots also provides crucial formal markers, establishing a sense of meditative routine by linking the characters’ journeys to recurring visual beats.

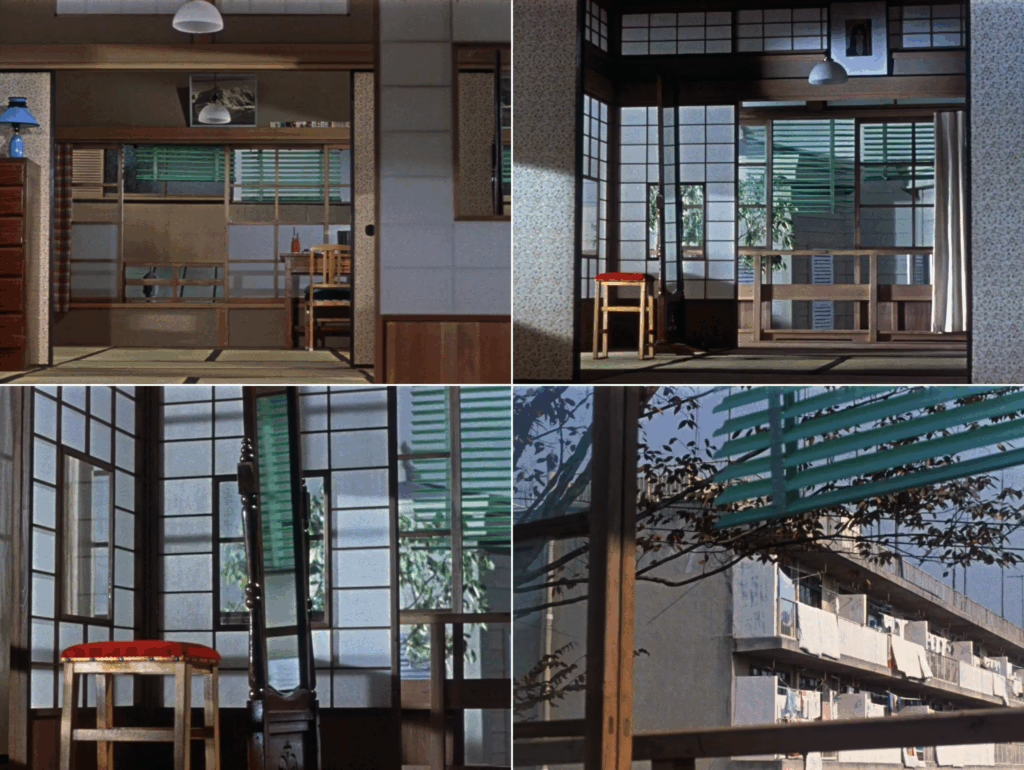

These rhythms continue on an intimate scale, cutting away to seemingly arbitrary items in the middle of scenes like a meditative sigh, and mystifying generations of film scholars with the famously enigmatic vase shot in Late Spring. Even more significantly, Ozu’s camera frequently inhabits the contemplative stasis of rooms for a few seconds before and after his actors enter and exit, finding tranquillity in the inertia.

This emphasis on negative temporal space is embedded within his narrative structure too, using ellipses to avoid depicting key plot points, and choosing instead to focus on their residual impact. Rather than attending Michiko’s wedding in An Autumn Afternoon for instance, he instead dwells on a standing mirror back at home, evoking her absence through related décor. In Tokyo Story and Tokyo Twilight as well, we only learn of character deaths through dialogue, understating the grief so we may feel it even more deeply.

Perhaps the most fundamental element of Ozu’s visual style though is his pure dedication to framing, often using shoji screens, doorways, corridors, and low furniture to slice up the shot into strong vertical and horizontal segments, and wrapping his characters up in compositions that alternate between cosy and confined. At the peak of his aesthetic accomplishment, he often uses multiple frames within a shot to create a funnelling effect into the background too, rigorously layering his interiors and emphasising the geometric rigidity of his mise-en-scène. Against these harsh lines and angles, staggered bodies rise up like hills in landscapes, softening the rigidity of the architecture with the natural asymmetry of the human form.

Ozu’s transition to colour in Equinox Flower marks a significant artistic turning point, accenting otherwise subdued palettes with bold flourishes – a red kettle for instance, or orange bottles of soda. Shots of commercial signage had already begun appearing in The Flavor of Green Tea Over Rice, but they take on a new potency once Ozu starts filming them in colour, enriching his pillow shots while registering Japan’s drift toward post-war consumerism. Similarly, his hanging laundry shots also adopt a rich vibrancy, evolving the ordinary textures of everyday life. By the time he directs The End of Summer, he perfects the art of colour compositions, while his following film An Autumn Afternoon stands as the final summation of his career.

Having lived with his mother for his entire life and never married, Ozu was left alone when she passed away in 1962. A year later on his 60th birthday, he also died of throat cancer, no doubt the result of his heavy chain smoking. Nevertheless, his filmography is extraordinarily prolific, and his influence has been enduring, constructing a cinematic language that is singular, consistent, and instantly recognisable.

Director Archives

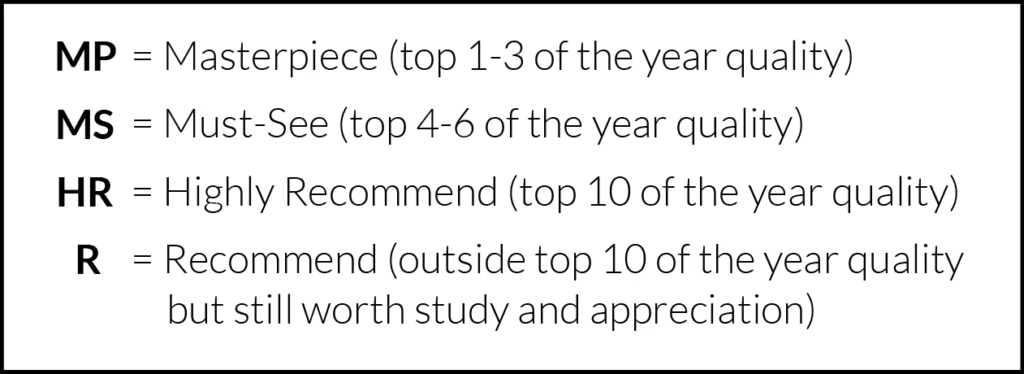

| Year | Film | Grade |

| 1931 | Tokyo Chorus | R |

| 1932 | I Was Born, But… | R/HR |

| 1933 | Woman of Tokyo | R |

| 1934 | A Story of Floating Weeds | MS |

| 1936 | The Only Son | MS |

| 1941 | Brothers and Sisters of the Toda Family | R |

| 1942 | There Was a Father | MS |

| 1947 | Record of a Tenement Gentleman | HR |

| 1948 | A Hen in the Wind | MS |

| 1949 | Late Spring | MS |

| 1951 | Early Summer | MP |

| 1952 | The Flavor of Green Tea Over Rice | HR |

| 1953 | Tokyo Story | MP |

| 1956 | Early Spring | HR |

| 1957 | Tokyo Twilight | HR |

| 1958 | Equinox Flower | HR |

| 1959 | Good Morning | R/HR |

| 1959 | Floating Weeds | MS/MP |

| 1960 | Late Autumn | HR |

| 1961 | The End of Summer | MP |

| 1962 | An Autumn Afternoon | MS |

Just about the best page you have written to date. Staggering congratulations!

The evolution you chronicle in the final segment might be the best dissection of any auteur I have read in a long while.

Thanks @rujkoc, appreciate it! These directors with longer filmographies are lots of work but very rewarding.