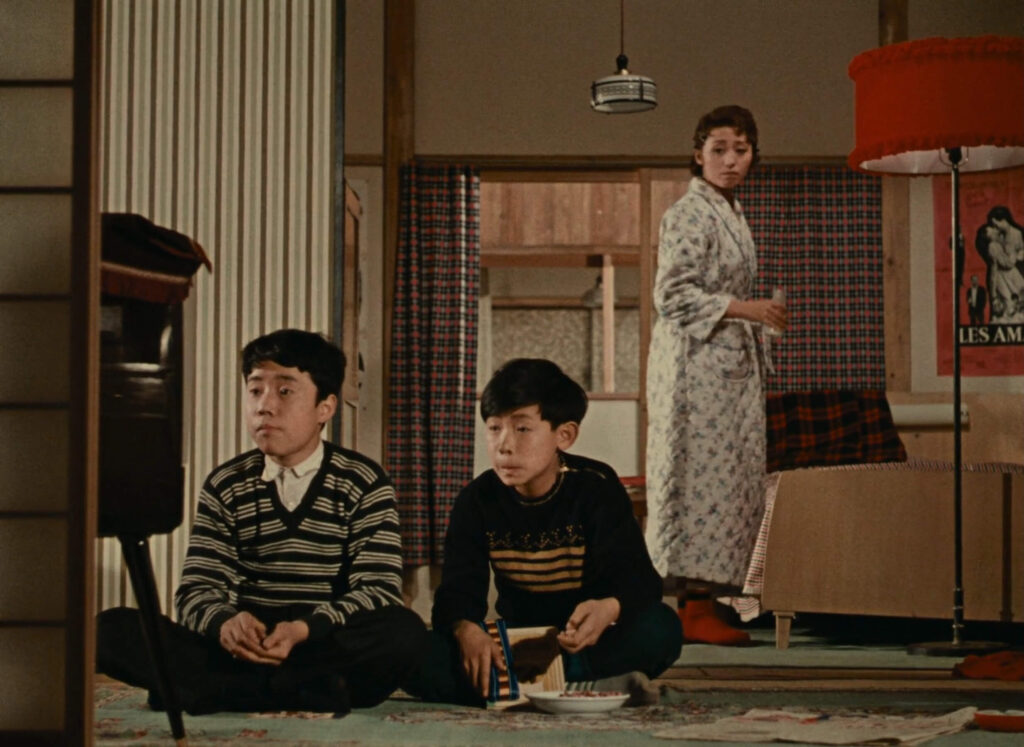

Yasujirō Ozu | 1hr 34min

Although Minoru and Isamu’s silent protest is aimed at their parents’ refusal to buy a television set in Good Morning, their frustration also extends to the superficial pleasantries exchanged between the grownups of this small Tokyo suburb. Neighbours here talk a lot without saying much at all, reducing the local women’s club to a simmering mess of gossip when the monthly dues go missing, and suppressing the unrealised love between mutual crushes Heiichiro and Setsuko. For the two young brothers, it is hypocrisy in its purest form, and a worthy target for their rebellion. If their parents insist that children are the ones who make noise without substance, then they will refuse to participate in social niceties entirely, choosing silence as a far more honest form of expression.

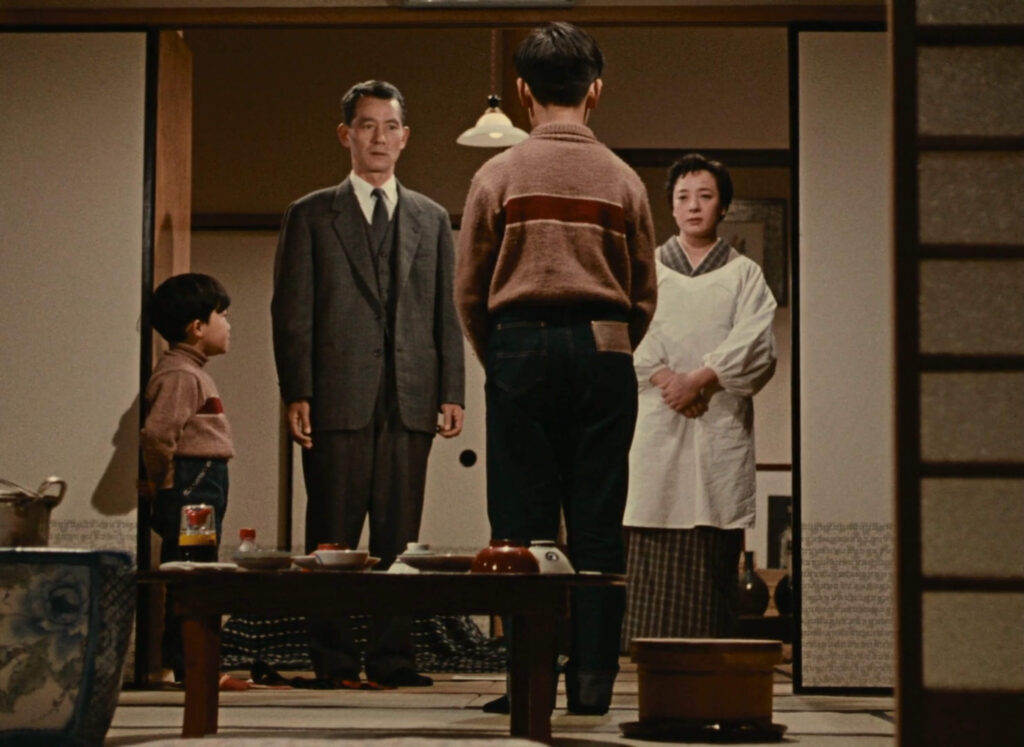

The rules that they set for themselves are simple. “Don’t answer, Isamu, no matter what they say,” Minoru instructs, allowing only a simple hand gesture to request temporary permission to speak. “Farting is ok,” he clarifies when his brother audibly lets one off, marking the official breakthrough of flatulence humour into cinema. This is not the first time Yasujirō Ozu has used comedy to underscore the incongruity of social norms, but Good Morning stands alone as his purest entry in the genre, channelling his Hollywood idol’s ‘Lubitsch touch’ which so elegantly blends high and lowbrow humour.

There is little explanation as to why this is otherwise such a visual and formal step back from the other Ozu films of this period, besides perhaps the shift in his own attitude when it comes to directing a story with amusingly low stakes. Good Morning is relatively light on layered compositions and narrative structure, instead adopting a looser, more episodic framing that unevenly navigates its various subplots. Within this pared-down aesthetic though, he still effectively adopts the perspective of his child protagonists through his characteristic ‘tatami’ shots, consistently placing the camera just a few feet above the ground. By combining this effect with the brothers’ identical costuming and mirrored blocking too, the unity of their mission is powerfully reinforced. When the older throws tantrums, the younger immediately follows suit, and it is made very clear who the leader and follower are in this mini-revolt.

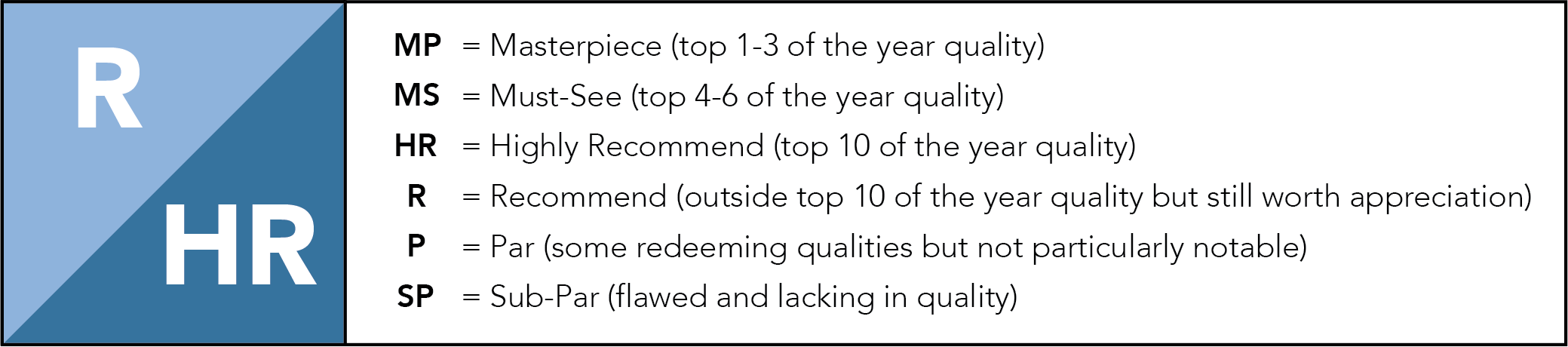

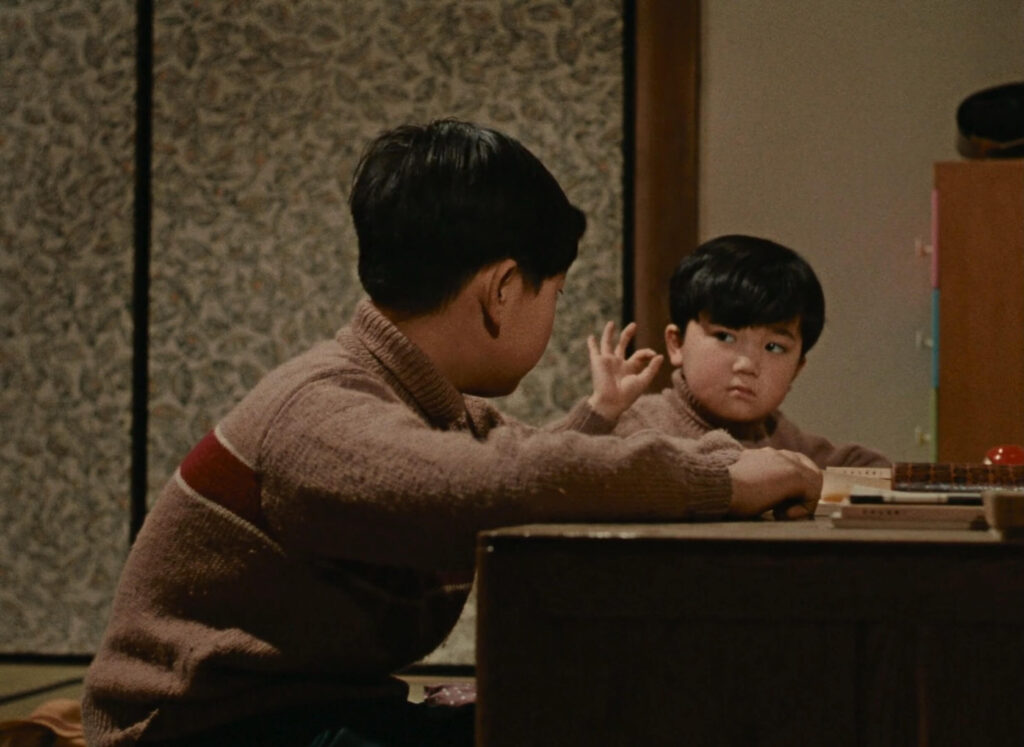

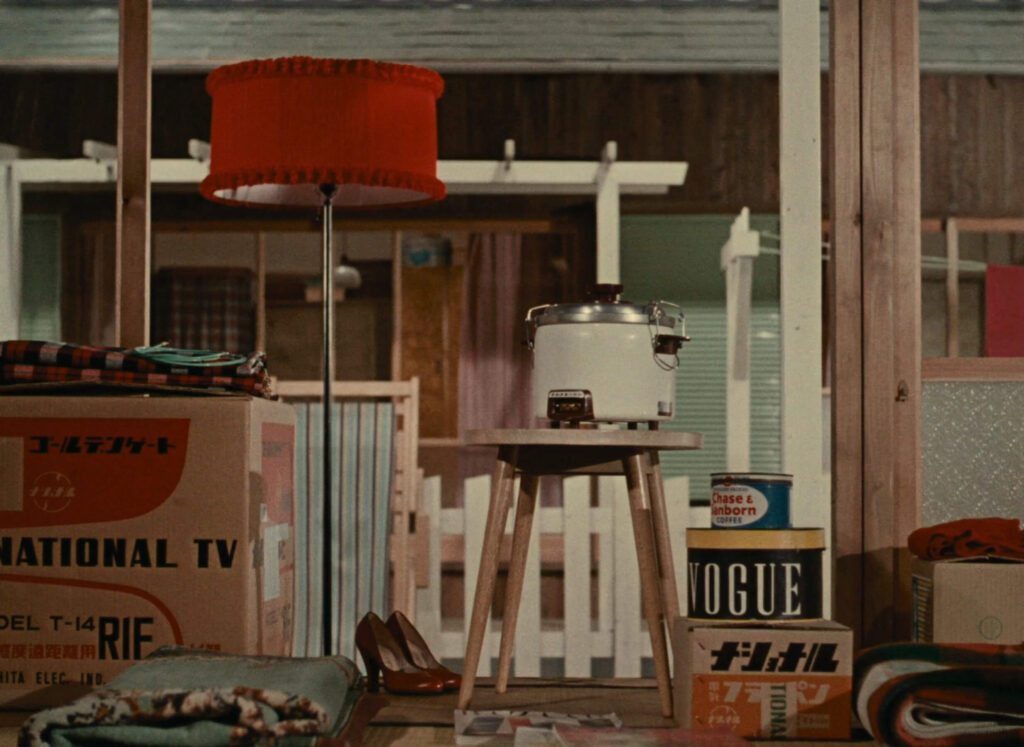

Of course, this generational divide is a common dynamic across Ozu’s films, particularly manifesting in Good Morning as the disruptive rise of consumerism among children. Parents Keitaro and Tamiko reveal their conservative attitudes early when they ban the boys from watching television at the neighbour’s house, partly due to concerns around the host’s profession as a cabaret performer – a further sign of Western modernity’s encroachment. While warm brown tones in Ozu’s mise-en-scene assert the parents’ sense of tradition and stability, bursts of branded, multicoloured décor reveal the cultural rupture that has taken place in these domestic sanctuaries, imbuing the sets themselves with that ever-present tension.

Not that complete conformity to traditional codes of conduct necessarily keeps the peace in this tightknit community. Honour and dignity are the most important values here, resulting in an ever-shifting blame game when the aforementioned club dues slip through the cracks, and great shame for Mrs. Haraguchi when she realises her mother misplaced them. She’s probably using the money to buy fancy new appliances for her house, the members cynically speculate, returning all the items she loaned them out of pure spite. When Minoru and Isamu ignore her greeting on the way to school too, her embarrassment deepens – though unbeknownst to her, this is nothing more than an ironic intersection of unrelated narrative threads.

Indeed, Good Morning may be Ozu at his most playful, even eschewing his traditionally restrained scoring for upbeat, whimsical music that would seem equally at home in a Jacques Tati satire. The silent protest at the narrative’s heart is mined for all its comedic value, especially when both brothers find themselves unable to verbally answer their teachers at school, and during a failed attempt at charades with their parents. The jokes inevitably circle back round to toilet humour too as the children eat pumice stones to increase the volume of their farts, resulting in a cheeky final twist on Ozu’s traditional pillow shots that strongly implies a hanging pair of shorts have been soiled.

Good Morning would not be a true comedy without the restoration of harmony to the Hayashi family though, delivered very simply with the parents relinquishing their old-fashioned ideals and purchasing a television set. On a more meaningful level though, Minoru and Isamu also learn an important lesson here, recognising the importance of ordinary communication to preserve the integrity of relationships. “Isn’t it necessary in our world?” their English tutor Heiichiro reflects, countering those accusations of insincerity, and it appears that Ozu ultimately agrees.

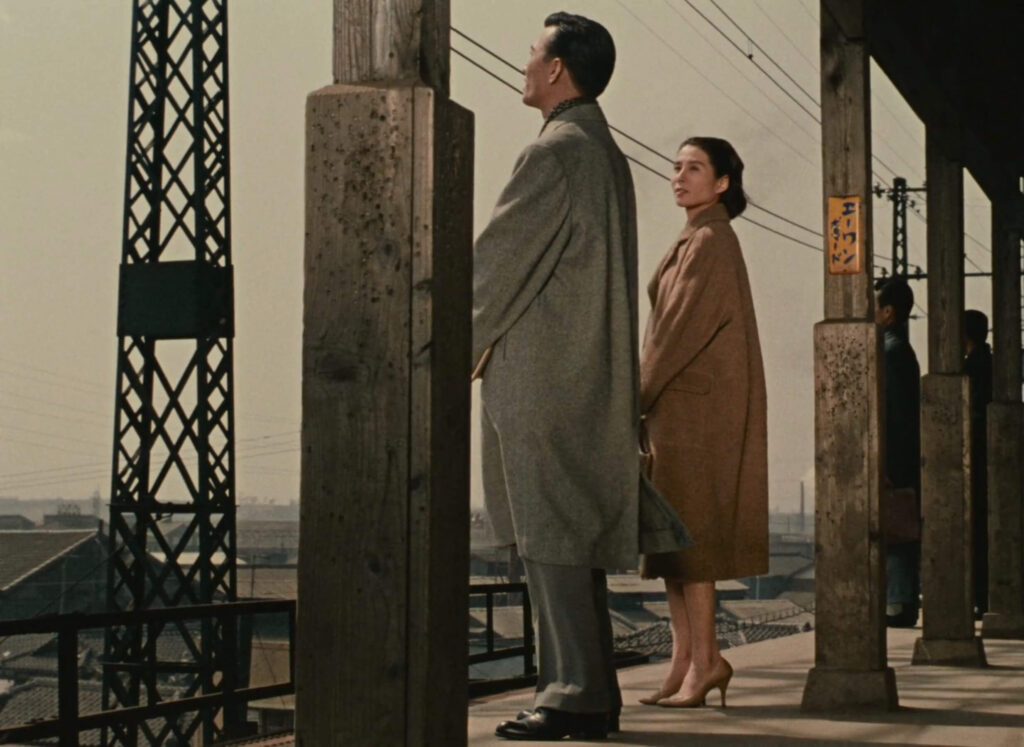

“A fine day, isn’t it?” Heiichiro later remarks to Setsuko at the train station where their paths cross each day. “Yes really, a fine day,” she responds, and not a trace of artificiality can be found in their small talk. For them and so many others, it serves as a stepping stone toward deeper connection, joining individuals together through shared routine. Even the most mundane interactions carry emotional weight for Ozu’s characters, and in Good Morning, it belongs at the very crux of a delicately balanced, ritualistic culture.

Good Morning is currently streaming on The Criterion Channel.