Yasujirō Ozu | 2hr 16min

There are few filmmakers who can accurately be called one of cinema’s great minimalists, yet simultaneously detail intricate compositions with such organised clutter. For Yasujirō Ozu, it was virtually second nature by the time he reached the pinnacle of his career in Tokyo Story, defining the inhabitants of an apartment building by its minutiae – a single tricycle left in a hallway, or neat rows of white laundry along a clothesline. In these quiet observations, we glimpse the precise order and precarious balance that governs the Hiryama family. While grandparents Shūkichi and Tomi cling to traditional values, their children and grandchildren pursue a more independent future, and Ozu binds all three generations together through the meditative routines of everyday life. As the centrepiece of this narrative, the Hiryamas form a delicate microcosm of post-war Japanese culture, gently drifting apart without fully breaking.

For Shūkichi and Tomi, negative emotions are sealed tightly behind beaming smiles and quiet hums, only ever sharing difficult sentiments in private moments. “We have children of our own, yet you’ve done the most for us,” Shūkichi remarks to his widowed daughter-in-law Noriko, warmly thanking her for the hospitality that Shige and Kōichi were too preoccupied to offer. They too are polite in their manner, but are far less adept at concealing their frustration over the burden of their parents’ visit. “Crackers would have been good enough for them,” Shige scolds her husband when he buys them expensive cakes, and she can barely hide her disappointment when they return early from a spa vacation organised to get them out of the house.

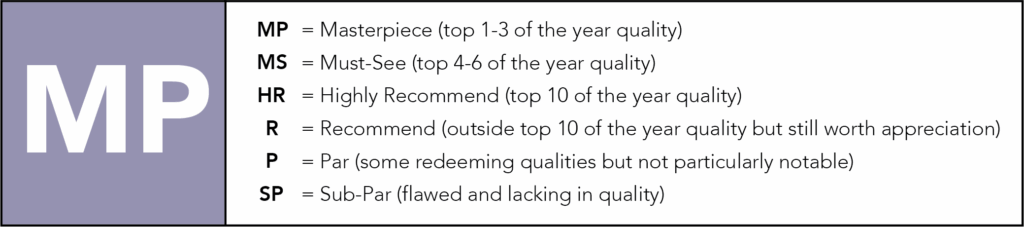

Indeed, tension is rife in Tokyo Story’s family drama, though comparing it to the bitter dynamics of an Ingmar Bergman film or Douglas Sirk’s melodramas reveals few similarities. Ozu’s friction seeks no urgent resolution, and instead sits in silent acceptance, inducing a Zen state that finds harmony in the paradoxes of the modern world. Smokestacks, powerlines, and train tracks impose their harsh edges on the curves of natural formations and traditional architecture, becoming the conflicting subjects of his characteristic pillow shots. Where a more conventional director might open a scene with a simple establishing shot, we instead slip through elegiac clusters of exterior views, lifting us outside the narrative flow and into a state of transient suspension. Just as rare as a minimalist who crowds his mise-en-scène is a master editor devoted to slow, measured tempos, and with roughly ten seconds dividing each cut in these montages, Ozu claims this rarified space as well.

Even beyond his pillow shots, Ozu resists dwelling in a scene solely for its drama. Instead, he prefers to open on an empty room before it’s filled with people, and linger briefly after their conversations have ceased – a contemplative cadence that has become his signature by this point in his career. The result is not quite the neorealist mundanity of Roberto Rossellini, but rather a naturalism that elevates everyday life to spiritual transcendence, stripped of obtrusive distractions and linking scenes through subtle, poetic logic. In one particularly striking match cut, we see Noriko fanning her parents-in-law, who then become the subject of Shige and Kōichi’s complaints as they mirror her action. Through this simple edit, Ozu delivers a visual rhyme of sorts, contrasting two distinct attitudes by way of shared, rhythmic motion.

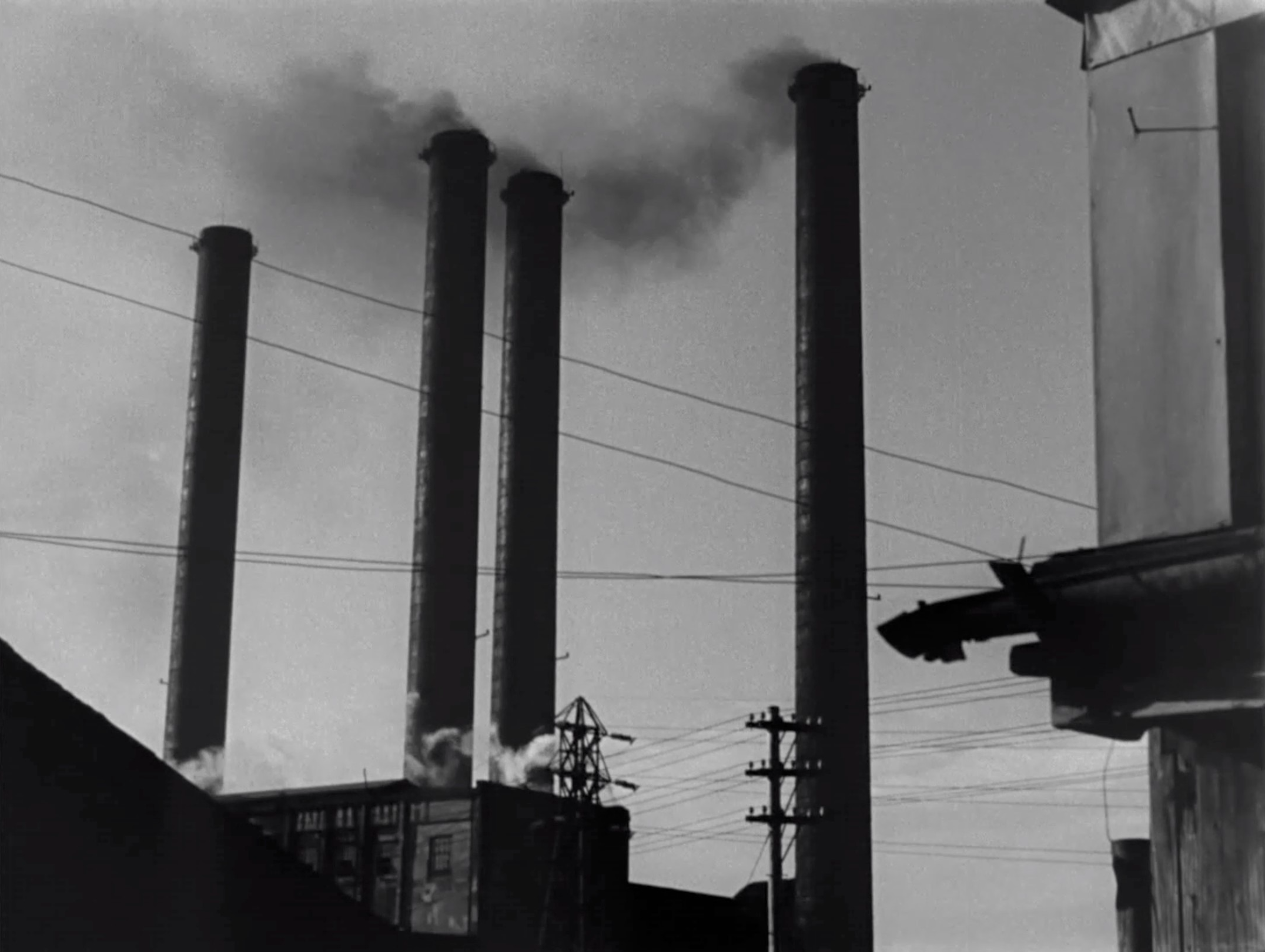

Besides a small handful of deliberate tracking shots, the camera almost never moves, consistently sitting in low ‘tatami shots’ that level with characters in their traditional kneeling position. Reflecting the rigorous consistency of the family’s domestic routines, Ozu selects a handful of compositions to reiterate as well, connecting us back to familiar visual beats. This not only synchronises us with Shūkichi and Tomi’s symmetrical ‘there and back’ journey across Japan, but also renders dutiful repetition as a formal, contemplative poetry that stretches through the entire film.

Ozu’s delicate framing is evidently far more attuned to his settings than his characters, often only observing family members from a passive distance as they drift through corridors and rooms. Just like the parallel lines and intersecting curves of the outside world, there is a geometric logic to his careful arrangement of each household item as they fill in space, obstruct compositions, and layer hallways with a striking depth of field. Even when the Hiryamas are not present, these homes carry the spirit of their day-to-day lives, carving out an unassuming beauty from each sake bottle, pot plant, and umbrella that sits in stasis between uses.

As these still images pass on by, time becomes visible in Tokyo Story, tracing Japan’s shift away from its complicated past and into an equally complex future. As innocent as Shūkichi and Tomi may be in their old-fashioned nostalgia, their disappointment overlooks their children’s emotional scars, with Shige particularly recalling how her father would often come home drunk late at night. Her treatment of her elders is no doubt harsh, yet her desire to keep moving forward is typical of her generation, particularly given the recent traumas of World War II.

Having lost their beloved Shōji in the Pacific War, the Hiryamas should understand this all too well, yet the pain of his memory hurts differently for each family member. Noriko hangs on dearly to the memory of her deceased husband, but when Shūkichi and Tomi notice their son’s framed photo still up in her house, she can barely address it without making a quick, convenient exit. Later when Shūkichi gently encourages her to let Shōji go and remarry, she accepts her new path with tender sorrow, finally taking on the lesson that her father-in-law has spent weeks learning the hard way.

For them, the older generation, the realisation of their fading relevance has settled in slowly. As Tomi sits atop a hill and watches her grandson play, she quietly wonders what he will be when he grows up, before pausing on a poignant question – “By the time you’re a doctor, I wonder if I’ll still be here.” Later during their getaway at the hot springs, Ozu foreshadows her eventual death further with a brief dizzy spell, and at least partially suggests that the commotion of modern Japan is somewhat responsible for her ailing health. The city’s noisy nightlife only adds to their discomfort too, subtly rendered in Ozu’s cutting between the elderly couple trying to sleep, the rowdy patrons down below, and those empty, perfectly aligned slippers sitting just outside their room.

Not one to let life-changing events break through his emotional restraint, Ozu refuses to even show Tomi suddenly falling sick on the train home from Tokyo, nor her eventual death back home in Onomichi. Instead, this information is relayed second-hand through other family members, finally united under a single roof in grief. Ozu’s rigorous blocking of mourners at the funeral preserves a sense of tradition that survives Tomi’s passing, and her children even contemplate their regrets over not being around more – “No one can serve his parents beyond the grave.” Quite predictably though, their empathy is short-lived. Out of her father’s earshot and barely noting his loneliness, Shige tactlessly expresses her wish that he was the one to go first, and it isn’t long afterwards that she and her siblings once again disappear back to their lives in Tokyo.

As flawed as the Hiryama children may be, Ozu’s meditation on generational changes is far from a condemnation of their modern values, and much more an elegiac reflection upon the natural course of life. A solitary Shūkichi grows increasingly isolated in Ozu’s mise-en-scène in the wake of his wife’s passing, mirroring the upright stature of two old, stone pillars as he gazes out at the rising sun, and later sitting alone among his furniture as his home’s sole remaining occupant. These settings are visual extensions of their occupants, but so too are these characters equally consumed by their dynamic environments, drifting along a steady stream into a fading past. Indeed, few directors have so eloquently aligned their aesthetic form and profound contemplations, crafting a visual language that complements the measured construction of their narratives. Even by Ozu’s standards though, Tokyo Story stands as his most carefully composed expression of melancholy acceptance, distilling time’s unyielding passage down to the transient distance between one fading generation and the next.

Tokyo Story is currently streaming on The Criterion Channel.

Pingback: An Inexhaustive Catalogue of Auteur Trilogies – Scene by Green

Pingback: The 50 Best Screenwriters of All Time – Scene by Green

Pingback: The 100 Best Edited Films of All Time – Scene by Green

Pingback: The 50 Best Film Editors of All Time – Scene by Green

Pingback: The 100 Best Shot Films of All Time – Scene by Green

Pingback: The 50 Best Cinematographers of All Time – Scene by Green