Ingmar Bergman | 4 episodes (40 – 48min) or 1hr 54min (theatrical cut)

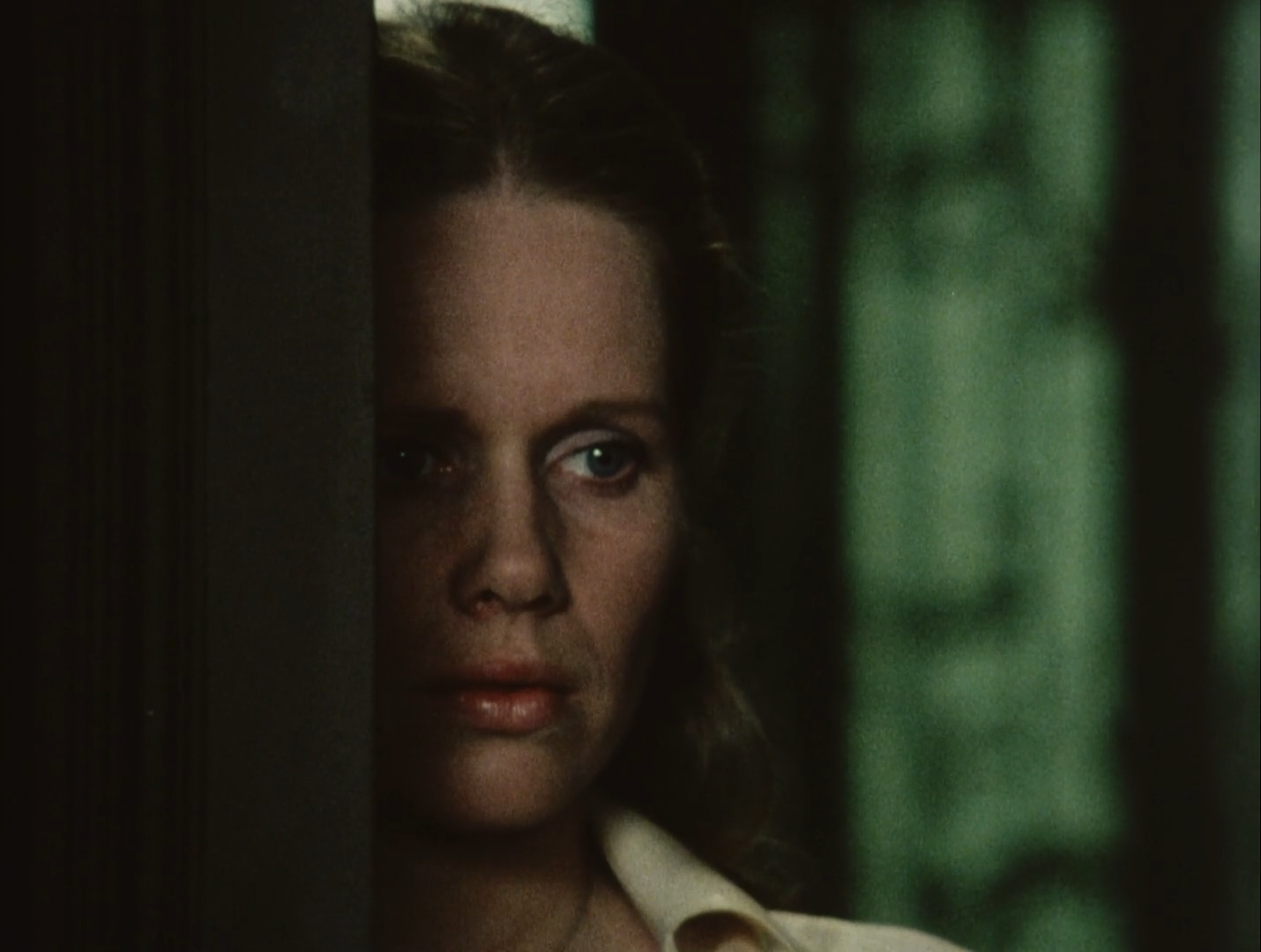

The firm line that Dr Jenny Isaksson draws between her professional work as a psychiatrist and her own personal traumas can only hold the façade of composure together for so long before it shatters. At first, it is barely shaken when she meets with her mentally troubled patient Mari, played by Kari Sylwan as the exact inverse of her saintly character from Cries and Whispers – tormented, withdrawn, and disdainful of those who claim a higher moral ground. On one hand, her cutting accusation of Jenny as a woman incapable of love could be little more than an attempt to inflict her self-loathing on others, but there are also psychological parallels here between doctor and patient that offer her vitriol a measure of truth.

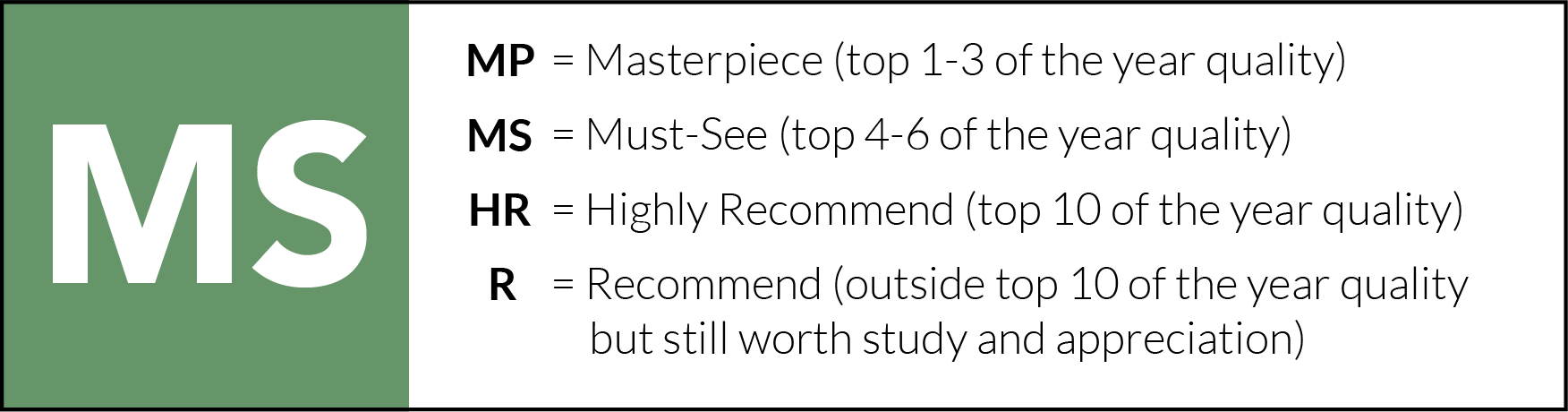

When Jenny comes home to her empty house one day and finds Mari curled up on the floor, Ingmar Bergman splits the space between them with a wall, manifesting that line dividing the two isolated halves of Jenny’s mind. Her confident authority as she calls for help on the telephone is almost instantly destroyed the moment a pair of trespassers appear and try to rape her, only to find penetration too difficult. Instead, they leave her lying on the floor in the same wounded state as Mari, with Bergman mirroring their anguish across both sides of the split shot that he has held for the entire agonising scene. Jenny’s psyche is still as fractured as before, but the bitterly repressed trauma that speaks to her through Mari has finally spilled out into reality, forcing a violent reckoning with her own physical and emotional fragility.

Much like Scenes from a Marriage, Bergman’s intent with Face to Face was to produce a miniseries for Swedish television, and then to cut it down to a film version for international distribution. Unlike his marital epic though, this intensive study of mental illness has faded into relative obscurity and consequently become broadly underrated. Neither this nor Scenes from a Marriage necessarily stand among his greatest aesthetic accomplishments, but his intuitive staging of profound personal struggles in both supports a pair of sharply written screenplays, seeking to understand the psychological weaknesses that force humans into emotional isolation.

So too is Face to Face yet another showcase of Liv Ullmann’s immense acting talent, earning Bergman’s close-ups with a vulnerability that exposes the raw horror of her internal conflict. In Jenny’s mind, pain and pleasure are virtually indistinguishable, as she confesses her dark desire that those trespassers were able to follow through with their rape just so she could feel some sort of connection to her humanity. With these conflicting emotional responses suddenly surfacing all at once, Ullmann seamlessly shifts from manic laughter into full-bodied sobbing and back again, and in refusing to cut away from his long takes of such visceral turbulence, Bergman proves himself equally dedicated to the realism of her plight.

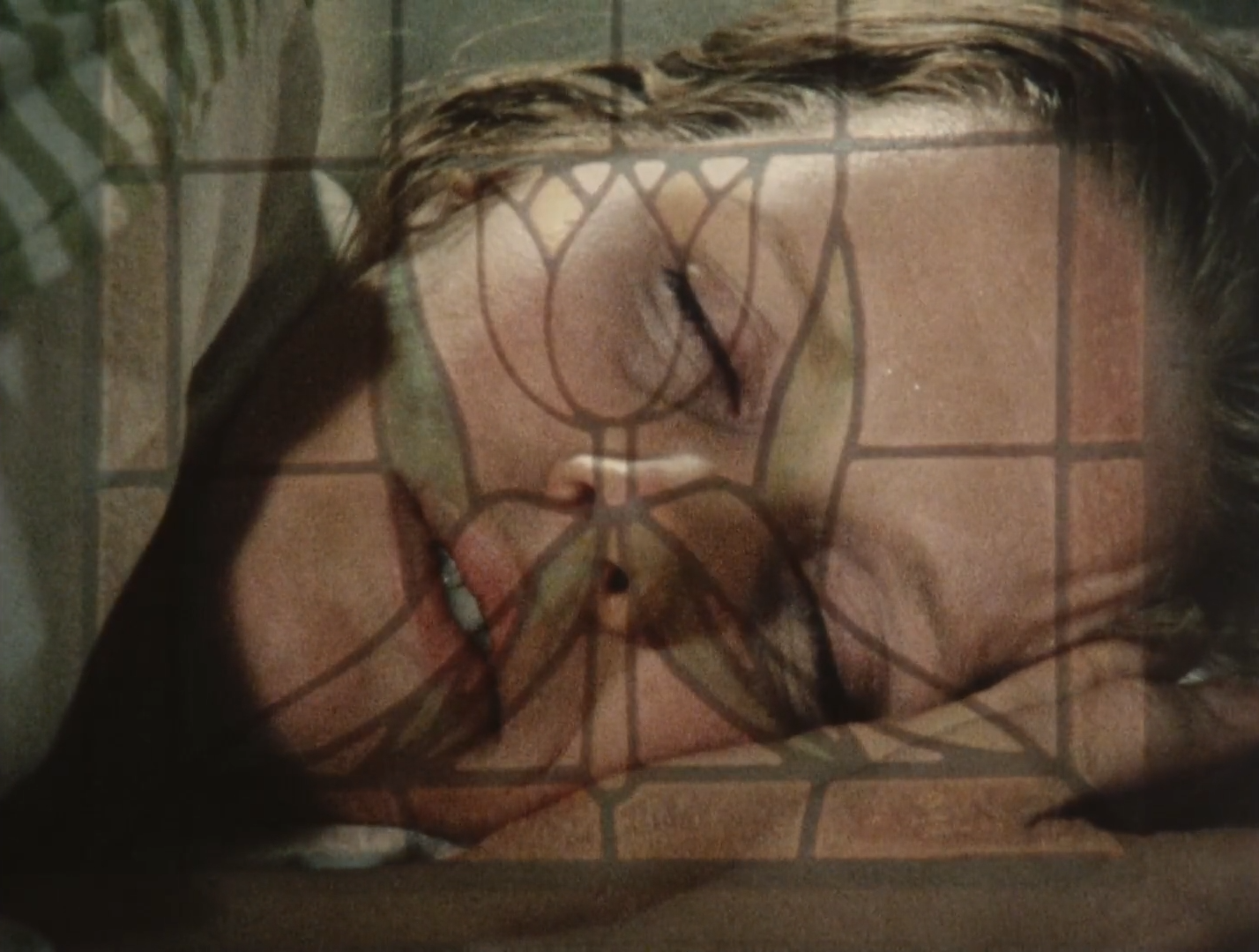

At a certain point though, realism is not enough to express the depths of her emotional torment. As she silently wanders through the bare, furniture-less house that she intends to sell, and later the cottage of her grandparents she is staying with, both become surreal limbos not unlike the hotel of The Silence or the family manor of Cries and Whispers. While her former home isolates her in bare rooms and corridors stripped of all their comfort, the dark green interior of the other is cluttered with photo frames and antique furniture that reek of old age. There, ticking clocks resonate through the repetitive sound design, as she disappears into dreams of an elderly woman with a single black eye. It isn’t just death that she fears, but the degradation of the mind and body that foreshadows its inevitable arrival at the end of one’s life, and Bergman wraps it all up into this sinister omen of mortality.

The mental disturbances that one man expresses to Jenny early on in Face to Face manifest even more tangibly as she sits on the verge of taking her own life, planting the self-destructive paradox in her head – could anyone feasibly take their own life out of fear of dying? It is certainly possible at least for Jenny, who seeks to take control of her fate by leaving a suicide note, overdosing on prescription pills, and quelling the inner turmoil that she has repressed for so long.

“I suddenly realise that what I’m about to do has been lurking inside for several years. Not that I’ve consciously planned to take my life, I’m not that deceitful. It’s more that I’ve been living in isolation, that’s become even worse. The line dividing my external behaviour from my internal impoverishment has become sharper.”

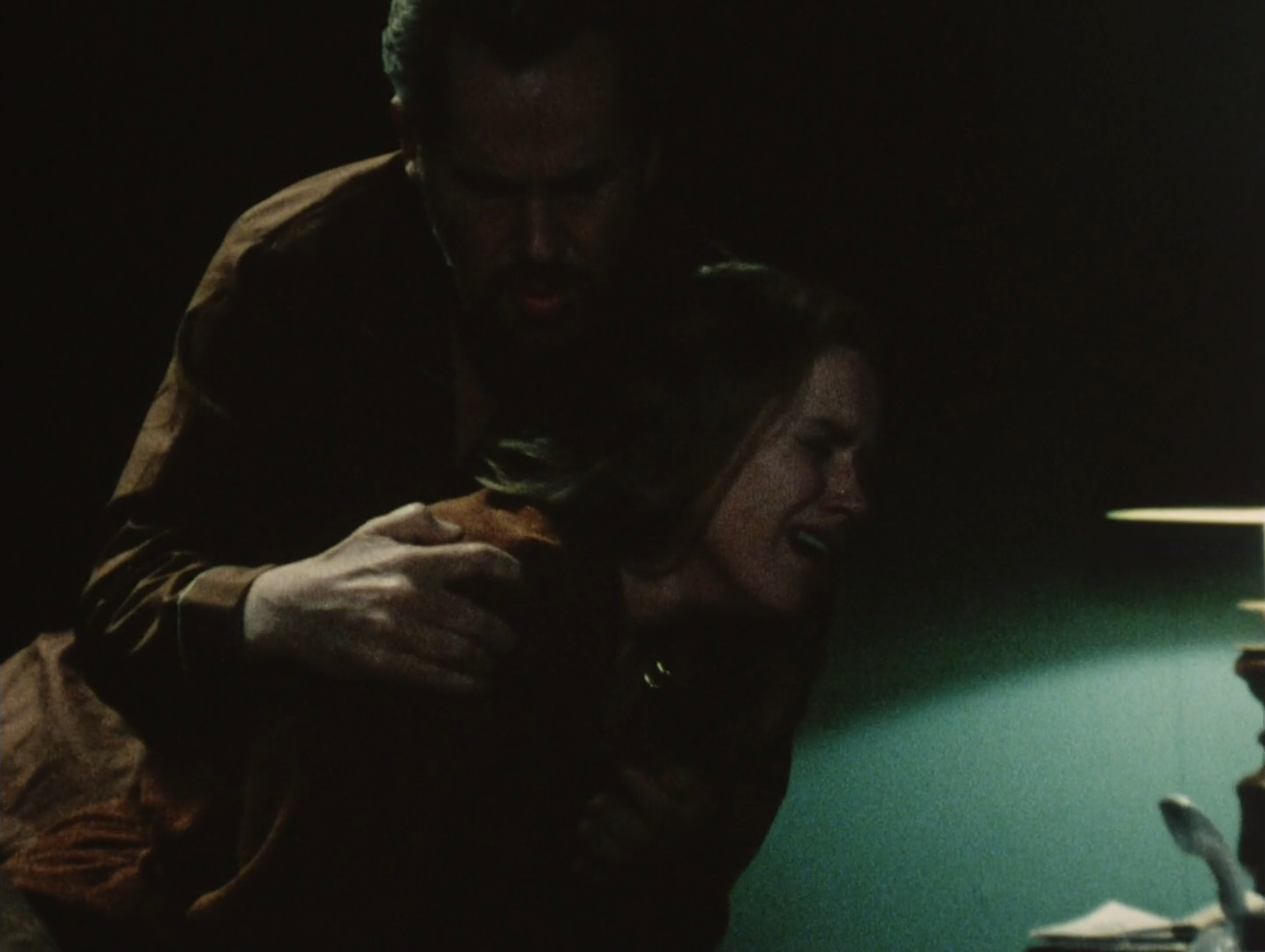

This is her “recovery from a lifelong illness” she claims, confessing that she cannot even find the tears to cry over her inability to appreciate beauty, before submitting to the creeping unconsciousness. Bergman’s camera gracefully follows the movement of her hand tracing the patterns of the wallpaper before it drops out of the frame, and as if accompanying her soul out of the room, we continue to drift along to the persistent ticking.

This is not the end for Jenny though, but merely a journey deeper into her subconscious, where Bergman’s surreal imagery exposes the fears that she has only ever verbalised to this point. This is also where Sven Nykvist’s cinematography truly strengthens, absorbing her into shadowy, decrepit dreams of her grandmother reading grim fairy tales to unsmiling audiences, inaudible whispers, and patients begging for her to cure their existential ailments. Her ineffective prescriptions do little to calm the crowd who grasp at her like lepers, holding her back from her daughter, Anna, who keeps running away.

Though Jenny drifts in and out of consciousness at the hospital, her grip on reality remains hazy in Bergman’s dreamy long dissolves, constantly pulling her back into those uneasy nightmares. The vivid red robe that she wears on this slippery descent to the core of her trauma makes for a number of striking shots against otherwise dark backdrops, framing her as a denizen of her own personal hell with that one-eyed crone as her only companion. Very gradually, the deathly terror surrounding this peculiar figure falls away, until Jenny embraces her strange maternal compassion by accepting her shawl for warmth.

Still, the foundations of her insecurities are not so easily vanquished, as Bergman finally draws her to the childhood ordeal that started it all – the sudden death of her parents in a car accident. Ullmann reverts to the mind of Jenny’s nine-year-old self as she faces their abandonment, banging on doors and heaving with sobs over her guilty conscience, only to hatefully scream at them to leave the moment they return.

“It’s always the same. First I say I love you, then I say I hate you, and you turn into two scared children, ashamed of yourselves. Then I feel sorry for you, and love you again. I can’t go on.”

It is one thing for Jenny to enter an unimaginable grief as an orphan, but it is another entirely to be completely cut off from any chance at resolving her troubled relationship with them, effectively damning her to a life of loose ends. It is no wonder she chose to become a psychiatrist. On some subconscious level, she sees herself in her patients, and through them feels just a little less alone in her suffering.

“To hold someone’s head between your hands… and to feel that frailty between your hands… and inside it all the loneliness… and capability, and joy, and boredom, and intelligence, and the will to live.”

Not that she has ever been able to offer them the same comfort. In its place she has established a cold emotional detachment, deciding that death is little more than a vague concept rather than a reality that encased her childhood in a tomb of endless mourning. Only now can she see it for what it is, as in one last dream she traps a copy of herself inside a coffin, nails it shut, and sets it alight, stifling her own panicked screams.

Healing may not come so easily through this renewed self-awareness, especially with the news of her grandfather’s stroke still hanging the shadow of mortality over her life, and yet for the first time she is able to view his old age with neither aloofness nor fear. As she watches her grandparents face their final days together, instead she sees “their dignity, their humility”, and confesses feeling the presence of something she has never experienced before.

“For a short moment I knew that love embraces everything, even death.”

Behind Jenny’s façade of stability is an overwhelming numbness, further masking a deeply repressed terror, yet buried even deeper than that within her psyche is an innate, abiding belief in humanity’s capacity for selflessness and devotion. It isn’t that she is incapable of love, as Mari tells her, but she has simply let it lie dormant to protect herself from the pain of continual loss – a pain that can only be ignored for so long, and whose only cure is a gracious acceptance of its inevitability. Even by Bergman’s standards, Jenny’s characterisation is profoundly layered with immense psychological depth, treading a fine line between realism and surrealism as thin as that which stubbornly divides her outer and inner identities. Only when this denial dissolves entirely and both come crashing into each other can any sort of self-actualisation be found in Face to Face, finally drawing a resounding peace from the chaos and trauma of being.

Face to Face is currently available to rent or buy on Vimeo.

Pingback: The Best Films of the 1970s Decade – Scene by Green

Pingback: Ingmar Bergman: Faces of Faith and Doubt – Scene by Green

Pingback: The 100 Best Female Performances of All Time – Scene by Green

Pingback: The 50 Best Female Actors of All Time – Scene by Green