Bi Gan | 2hr 40min

A candle that does not burn may live forever, yet in the dying light of Resurrection’s reveries, there is a bittersweet melancholy attached to such awed visions of immortality. To dream is to wander liminal, illusory landscapes, surrendering to a small death each time they recede from our senses, so it is fitting that those in Bi Gan’s abstract dimension who have given up this hallucinatory experience now attain the ability to live forever. The few who reject such longevity are known as Deliriants, while those who hunt them down are the Big Others – though Bi is not so concerned with logical constructs of worldbuilding. Resurrection’s futurist framework is merely a launchpad to more transcendental ruminations, pondering the impermanence of being, and shapeshifting its cinematic form as freely as the central Deliriant who drifts between phantasmic dreams.

For Bi, there is little distinguishing this character from the medium containing him, rendering him a tragically monstrous manifestation of that threshold between illusion and existence. The Deliriant is cinema incarnate, bearing the bald head and pale skin of the vampire Nosferatu, yet possessing a lonely, mortal soul. While the rest of society has turned to opium as a psychoactive substitute for dreaming, he is an addict of imagination, tortured by the anguish of unfathomable fantasies and the isolation of reality. Taking pity on this misbegotten creature, the Big Other which has sought him out agrees to put him out of his misery, installing a projector inside his torso and letting the film reel play out until his dreams end. Like an entire life flashing before one’s eyes, the history of cinema thus unspools, fading into oblivion through narrative cycles of loss and rebirth.

Resurrection no doubt flows from the same visionary filmmaker who channelled Andrei Tarkovsky’s poetics in Kaili Blues and Long Day’s Journey into Night, though Bi’s shift away from evocations of personal memory to a broader collective consciousness is profoundly apparent. Even more distinct are his meditations on ancient Chinese philosophy, specifically reinterpreting Taoism’s embrace of the ineffable as a realm beyond any artistic medium – “The greatest music barely makes a sound, the greatest image has no shape.” By structuring Resurrection around the six doors of Chan Buddhism as well, Bi imbues it with the very essence of sensory awakening, contemplating our worldly perceptions through the eye, ear, nose, tongue, body, and mind – then shutting each down as the Deliriant fades away. This is not something to fear, Bi assures us, as the beauty of cinema is in its impermanence. For it to be reborn, we must first lay it to rest, and simultaneously free our souls from those illusions which prevent true enlightenment.

As long as the Deliriant remains alive though, Bi delights in tantalising those senses, joining the Big Other as she witnesses that which has captivated his speculative mind. One hundred years of cinema and Chinese history come together in Resurrection’s fluid mythology, ingeniously reinventing its visual language as decades slip by, and absorbing us within endlessly regenerative tales.

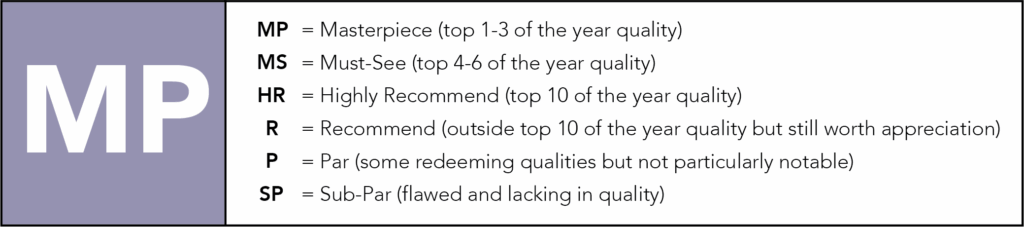

In the first instance, the era of silent cinema defines the ‘real’ world, stripping back all diegetic sound in exchange for an orchestral score, antiquated intertitles, and distinctly expressionistic designs. This is evidently the story of sight, celebrated in breathtaking, curated visuals that merge futuristic abstraction with the enduring nostalgia of the past. When the Big Other first enters the opium den which the Deliriant hides beneath, a wide shot of the room sets the scene like a diorama, arranged by giant hands reaching from beyond the frame. Rather than black-and-white, a green and gold colour palette infuses this prologue with an otherworldly luminescence, while angular, geometric architecture directly evoke the stark chiaroscuro of Fritz Lang and Robert Wiene.

As Bi’s camera cautiously follows a creeping shadow through jumbled, fragmented set pieces, he further cements this F.W. Murnau influence, revealing the Deliriant’s lair as a backstage, smoke-infused labyrinth. A brief dip into slapstick recalls the Lumière Brothers in recreating the very first gag captured on film, but before Bi can further explore this comedy, the silent homage comes to end with the first intrusive, diegetic noise. Reaching through the fourth wall and crumpling up an intertitle, the Big Other collapses the cinematic illusion, before guiding us into yet another realm submerged deep within the Deliriant’s subconscious.

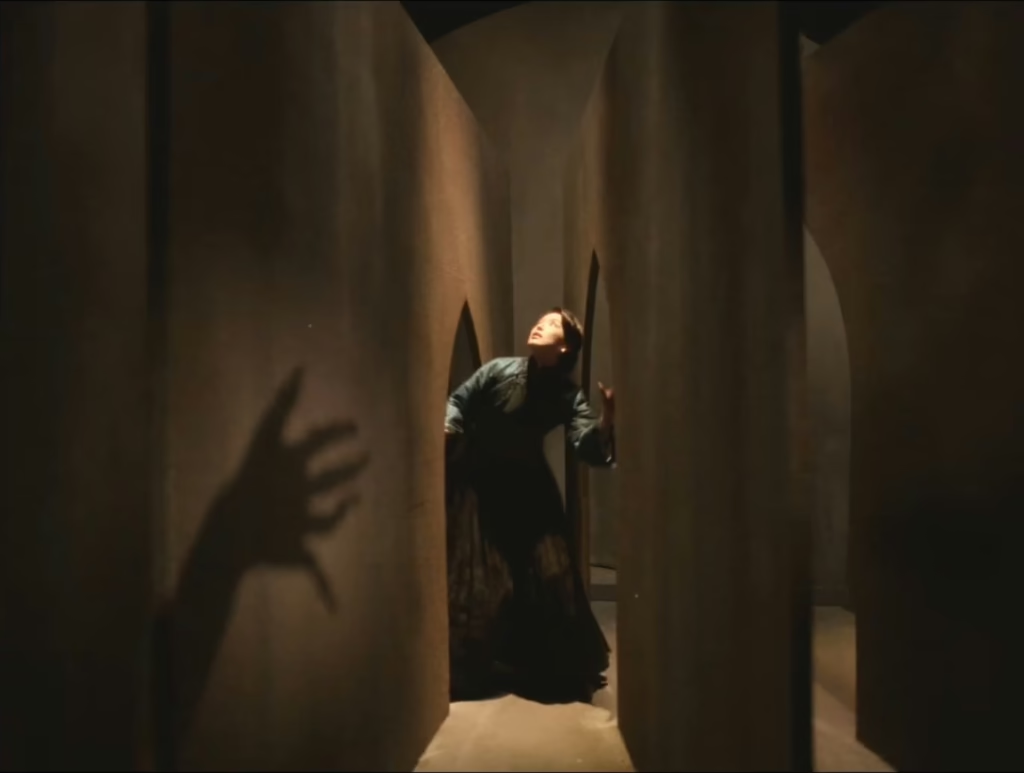

There begins the first of several dreams that draw this filmic monster towards his demise, presenting a dark wartime setting composed of desaturated shadows and veiled intrigue. No longer appearing as a misshapen creature, the Deliriant is now Qiu – a brooding noir protagonist accused of murder, pressed by the unyielding Commander to reveal the location of a mysterious suitcase. As Bi’s narrative winds itself into a tangled spiral though, it is evident that he is far more invested in impressionistic textures and existential tension than any mechanical plotting.

Within the vast train station of this episode, falling bombs send glass raining to the ground like shards of light, while long dissolves ethereally blend movement across time in static frames. This is the first of several dilapidated settings we will encounter across the Deliriant’s dreams, reflecting his own physical decay in rainy backstreets and dingy basements, while the termination of his hearing subliminally emerges in the narrative itself. Bi recalls The Lady from Shanghai within a mirror shop where the Commander shoots at Qui’s deceptive reflections, echoing the Deliriant’s fragmented identities, and concluding with Qui partially deafening the Commander by stabbing him in the ear. Of all the secrets that could have been hidden inside the suitcase too, it is a theremin which the Commander ultimately discovers – an instrument played without physical contact, yet which he uses to perform a wavering rendition of ‘Come, Sweet Death’, before condemning both himself and Qiu to a blazing self-destruction.

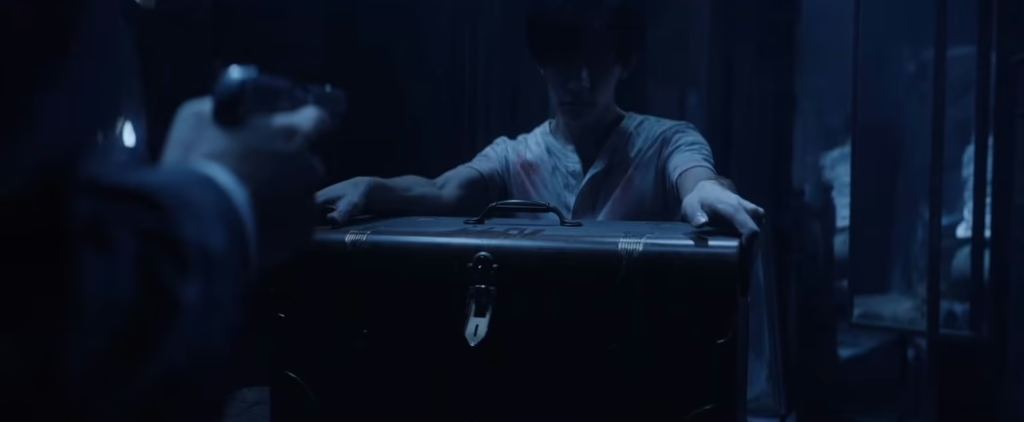

This film noir homage is by far the most cryptic episode of Resurrection, anchored primarily in the symbolism of aural vibrations, and resonating Bi’s metaphysical language of dreams in the image of Tarkovsky and Lynch. Here, between the Deliriant’s hallucinations, we also encounter a motif that Bi continually revisits. As the Big Other’s voiceover describes the creature’s waning bodily functions, a wax candle melts away to nothing, formally distilling Bi’s metaphor of mortality. Life and cinema dwindle with the fading light, and when the Deliriant emerges twenty years later during China’s Cultural Revolution, the acrid cultural memory of this period is given tangible form in the anthropomorphised Spirit of Bitterness.

By setting this tale in an abandoned Buddhist temple far from civilisation, Resurrection skilfully dodges any explicit depictions of this controversial period, as well the risk of censorship. Instead, it manifests in the piercing cold atmosphere brought on by the smothering snowfall, and that ghostly entity which emerges from the aching tooth of ex-monk Mongrel. Split diopter lenses bridge the distance between man and spirit, the latter of which has discomfortingly taken on the appearance of Mongrel’s father – and soon enough, we learn why. For the Spirit of Bitterness to reach enlightenment, Mongrel must participate in a ritual of confession, and eventually atone through a degrading, deeply ironic metamorphosis.

This episode is Bi’s take on a Chinese folk fable, tracing a passage from karmic reckoning towards release, yet isolating his characters in the desolate ruins of a temple that has lost all human warmth. In deliberate tracking shots, the camera flies like wind close to the frozen ground, while the shrine itself proves to be a solemn, imposing piece of architecture with its flying eaves and elegant tiling. Once again though, it all melts away like wax as the Deliriant’s dreaming mind slips forward another twenty years, and finds itself in a far more material setting.

The Chinese economic reform brought a period of social mobility and moral improvisation in the late 1970s, and through the bright, sun-dappled story of con artist Jia conspiring with a young orphan girl, illusion is repurposed as a tool for survival. An ‘Old Man’ who promises riches to anyone who can prove some psychic ability becomes their target, and by teaching the girl a trick that feigns the ability to smell any chosen playing card, Jia effectively demonstrates that persuasion matters more than authenticity.

Between the girl’s endless riddles and Jia’s wry answers, a sweet, fatherly relationship emerges, rooted in the shared play of imagination. “What can one person do that two people can’t?” she ponders. “Dream,” he responds, though of course Bi recognises the limits of his insight within the broader scope of Resurrection’s collective cinematic reverie. Deprived of any spiritual direction, Jia’s wisdom falters, denying the girl the father she seeks and sealing his fate at the hands of thieves.

This episode may be the least stylistically elaborate of the film, yet the natural golden lighting and scintillating score offers a soft, enveloping warmth, grounded in a realism that has been absent until now. Only in its closing moments does the first hint of mysticism emerge, prompted by the Old Man’s request for help. It is no wonder he smells of formaldehyde, a chemical used to preserve corpses – consumed by grief, he has embalmed his own life around the burnt, illegible letter his daughter wrote shortly before perishing in a fire, suspending his loss in time. Quite remarkably though, the girl succeeds in smelling out this message as well, revealing her uncanny intuition of a world hidden beneath appearance.

Finally, Resurrection approaches the last of the Deliriant’s dreams, and no doubt the most visually impressive of them all. Bi’s long, wandering takes have become his greatest trademark, immersing us in a trancelike continuum of time and space, and here it visits the docks of a city on New Year’s Eve, 1999. An angry red wash illuminates this littered waterfront where gangster Apollo roams in double denim and eventually meets Tai – a stylish young woman who might as well be ripped straight from a Wong Kar-wai film. Drizzling rain collects in puddles that catch the crimson neon glow of passing lights, and as Apollo follows Tai through shady alleyways, abandoned nurseries, and nightclubs, the Deliriant’s dream explicitly dramatises questions of immortality through a supernatural lens.

Within the unbroken, tactile immersion of this forty-minute tracking shot, Bi privileges the sense of touch, and further embeds it in a pair of confessions – Apollo has never kissed a woman, and Tai has never bitten anyone. She belongs to a clandestine cabal of vampires led by the enigmatic Mr. Luo, introduced by a seamless adoption of his point-of-view which underscores the dream’s fluid subjectivity. Commanding fear and reverence across this red-light district, Luo’s dominion is threatened the moment Apollo storms the club to rescue Tai, as the lighting abruptly drains to teal and the camera snaps free of his gaze – yet still his power holds as he croons karaoke in close-up, his henchmen assaulting Apollo in the background.

As Apollo and Tai finally reunite at dawn by the docks, no longer is the city flooded with an artificial, electric glow. Sailing a boat towards the sunrise, the soothing blue light of dawn washes over the river, heralding a new millennium that Apollo has expressed concerns may bring the end of the world. In this romance, Bi parallels the same asymmetrical divide that has emerged between the Deliriant and the Big Other, forging intimacy between the mortal and the immortal – the latter of whom is revealed to possess an equally existential loneliness. Trying to save her lover, Tai finally bites Apollo, yet the act only tragically succeeds in delivering him to the same fatal destiny that has claimed his reincarnations across each dream.

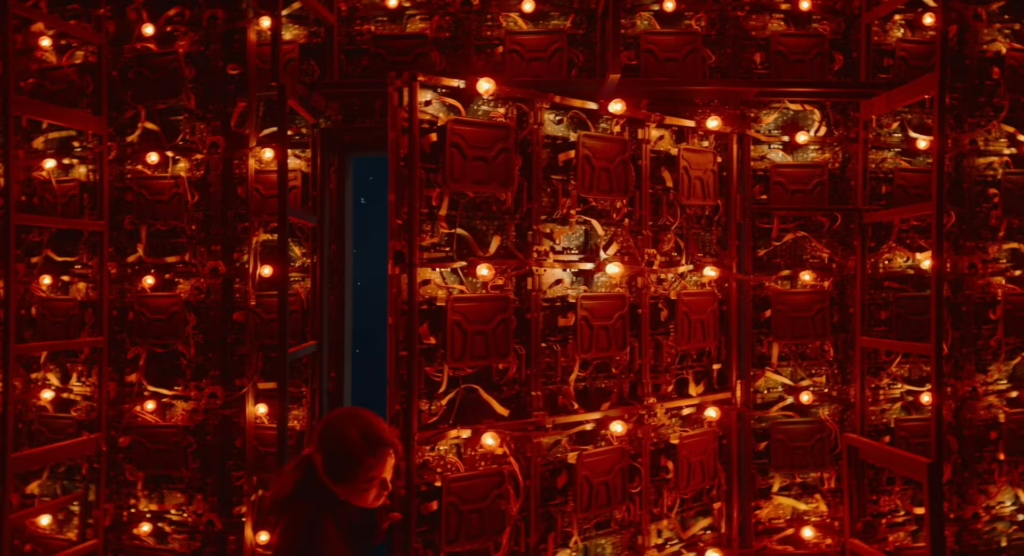

Even the eternal cannot escape the inevitability of loss, and as the Deliriant’s mind finally yields to dissolution, the Big Other ritualistically prepares his body for a passage into the beyond. Though he appears as Apollo in death, she shaves his head and dresses him in his Nosferatu regalia, as if to reset the illusion. Through a lattice of red bulbs and circuitry, a doorway opens into a rippling blue pool of water, and she releases him into its depths – for only in surrendering to mortality may the Deliriant be resurrected for another audience, and shall we return to reality.

Art is no replacement for life, Bi is sure to remind us. “The greatest image has no shape,” we are told, and for all its beauty and spectacle, cinema is constrained by time, space, and our sensory perception. The goal is not to save it, but to let it die so that we may live, releasing our worldly attachment and stepping into the boundless flow of the present.

Still, this does not diminish cinema’s gift of shared reverie in Resurrection. For the few hours we lend it our senses, the monster lives. In that fleeting fusion of audience and film, our consciousness entwines with its illusions, and we treasure each ephemeral sensation before it fades. Just as this surreal odyssey opened with a crowded movie theatre of faces staring right back at us, Bi now draws it to a close with a theatre of wax, populated by figures of pure light. No projector is needed – the audience members are the luminescence that makes the film possible, each inevitably flickering out of existence as the auditorium around them melts away. Bi’s metamodern autopsy of cinema and its sensory illusions may be formally elusive, yet by asserting itself as one of the medium’s most transcendent accomplishments in recent years, Resurrection majestically enacts the intersection of art and reality as a transient, bittersweet exchange.

Resurrection will receive an official Criterion release on April 21, 2026.

I have never heard of this movie before, and you have it as a Masterpiece. How do you find movies like this? I haven’t even seen it on any “best movie” lists.

Hi K you should join our cinema archives discord server, we run a lot of community events and also frequently mention what 2025/2026 releases we are anticipating most so you will be less likely to miss out. Here’s a link: https://discord.gg/FwDBnt6c

Matthew from the Discord server shared the trailer back in November and it looked too gorgeous to pass up. Since then Bi Gan’s two other films have made their way to the Criterion Channel, and both were very impressive which raised my expectations for this even further. The TSPDT consensus has put it as the 19th best film of 2025 which is a fair bit off – but it’s something at least.

Oooohhh, now I need to keep an eye for when this comes out physically

I’ve got to be honest: I’m surprised by the fact that so many people from the film community have never heard of this film before. It premiered at Cannes last year and got a special prize by the jury, and it’s found its way into a few film festivals here in Europe. I’ve seen it twice by now, both times on a big screen, and even though I don’t quite have it as a masterpiece, I think it’s VERY close. It’s surely one of the most ambitious films I’ve seen in a long time, and there are some passages (most of them on the first, third and fifth sections) that are truly breathtaking. I’m sure its inscrutability can get a little frustrating for some people, but as a piece of art, its beauty and its power are undeniable. I would place it fourth in my personal 2025 ranking. I still think I enjoy Long day’s journey into night a little bit more though.

It’s been pretty scarce in Australia unfortunately. I could only find two cinemas in Sydney playing it for a limited time, and then one other in Melbourne. I’m lucky enough to be seeing it again next week though! It’s been a while since I’ve been so blown away on a first viewing by a new film.