Clint Bentley | 1hr 42min

Ever since Robert Grainier unwittingly assisted in the lynching of a Chinese immigrant on a railroad construction project, he has anxiously felt the shadow of some dire, fateful punishment waiting to exact its toll. He did not know what was taking place when a small group of fellow workers picked up the man, carried him to a bridge, and hurled him over the edge, but the fleeting moment that he joined in has haunted him ever since. “What did he do?” he frantically repeats, grasping for some sense in this violence – though given Train Dreams’ setting in early 20th century Idaho, it isn’t hard to recognise the malicious prejudice driving this act.

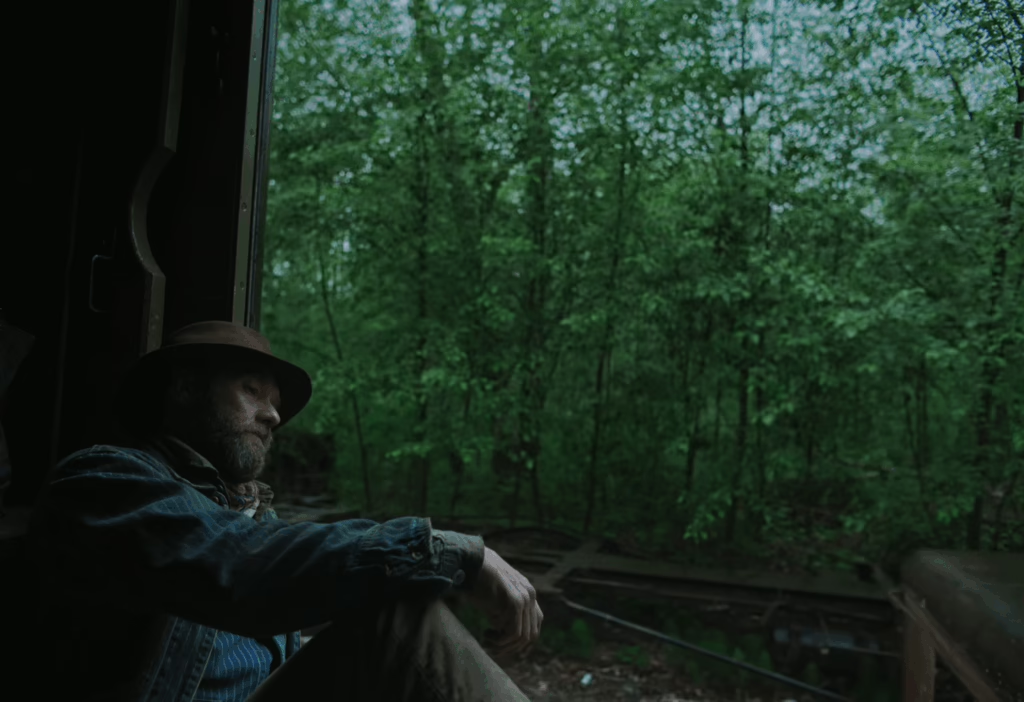

Through Clint Bentley’s patient, impressionistic lens, we too sense the guilt stalking Grainier wherever his labour takes him in the Pacific Northwest. Rapid montages break up the meditative pacing with recurring nightmares of spinning wheels, headlights piercing smoky darkness, and the doomed Chinese man standing in the path of an oncoming train, reminding Grainier of the reckoning that patiently waits in his future. After his fellow worker Arn perishes beneath a fallen tree branch as well, he can’t help but feel that it was meant for him, and that his time is almost up. When tragedy does finally strike in Train Dreams though, it steals something far more valuable than his life. Suddenly, this broken figure finds himself cast into a lonely, unsentimental world, helplessly watching it march on in the name of indifferent progress.

With an omniscient narrator guiding this historic tale as well, Train Dreams often reads like a contemplative, archival chronicle of a bygone era. Terrence Malick may be Bentley’s primary influence in his breathtaking photography of rural landscapes, yet echoes of Barry Lyndon and Y Tu Mamá También linger in the detached, observational voiceover, infusing its nostalgia with a fatalistic clarity that peers beyond the horizons of time. The railroad that Grainier has tirelessly worked on may be a great feat of engineering in 1910s America, but as the deadpan narration informs us, it will be rendered obsolete in ten years by the bridge of concrete and steel built just upstream. Everything that Grainier holds dear is but a transient heartbeat in the grand scheme of history, and Train Dreams watches on with lyrical melancholy as it is wholly consumed by industry, ambition, and time.

This existential hollowness has long lingered in Grainier’s consciousness too, we learn in the opening minutes, denying him any sense of purpose or passion for many years. Only when he meets his future wife Gladys does his future begin to take shape, and fully illuminate once they welcome their daughter Kate into the world. Bentley’s visual storytelling flourishes in the idyllic paradise of their humble countryside home, stripping dialogue to stretches of silence as they handcraft fish traps and picnic by the Moyie River. Wide-angle lenses breathe in the negative space of pink, blue, and orange skies, beautifully tinted by the setting sun’s natural light, which in turn highlights the textures of rippling water and billowing clouds. Even as seasonal work in faraway locations renders Grainier a lonely stranger in his own life, this sanctuary of love becomes the axis around which his existence turns, radiantly glowing with the false promise of permanence.

Just as there was no meaning behind the murder of the Chinese immigrant, there is no sense in nature’s ruthless reclamation of Grainier’s family, devastatingly reducing his world to ash in a raging forest fire. Arriving home at the end of another logging season, he finds the train station in chaos and black smoke pluming into the sky. Venturing through this flaming hellscape to save his wife and daughter, he instead finds the empty, burning remains of his cabin, and even when the embers finally cool, still he can’t remove himself from its charred remains. Rain drenches his clothing as he mourns his wife and daughter, and in Joel Edgerton’s quiet, internalised performance, the weight of grief seems to press the air around him.

Time continues to slip through the elegiac rhythms of Bentley’s editing as Grainier rebuilds the cabin, works on the homestead, and finds companionship in a red dog, all while holding onto hope that his family may one day return. He still hears Gladys’ whispers and Kate’s giggles on the wind, yet he can’t quite bring himself to face them, lest they should disappear entirely. Although there is little plot to speak of here, Train Dreams keeps us in its mesmerising grip as society slowly shifts around Edgerton, whose hollow gaze and restrained physicality remain the only true constant in this mournful testament.

Perhaps this longing for order in the face of inevitable decay is why Bentley imbues his compositions with such meticulous rigour, often blocking workers like subjects in historical photographs, and distinctly departing from Malick’s free-flowing style. It isn’t unusual for Bentley to isolate them in the centre of his symmetrical frames as well, like artefacts of historical study, while the camera steadily zooms out through long, slow takes. Especially when we consider those recurring symbols of endurance which punctuate the film’s transience, Bentley crafts some magnificent visual tableaux, most notably in the old pair of boots nailed to a tree as an eternal memorial to loggers who were killed on the job. They may grow weathered with the passing years and weeds may creep through their seams, yet each time Grainier recalls them, they take on greater significance in their struggle against time and decay.

Just as his vivid imagination once haunted him with ominous nightmares, so too do memories now take tangible form, summoning Gladys and Kate in spectral flashbacks and hallucinations that blur decades into a single aching present. Painful they may be, but these reveries remain Grainier’s last sanctuary as men soar into space and steam trains surrender to electricity, transforming the world beyond recognition. Human connection remains scarce in his older years as he turns to carriage driving, though through his fleeting friendship with out-of-towner Claire, the ache of transience seems to soften. “The dead tree is as important as the living one,” she reflects, drawing wisdom from nature to find solace in her own grief.

“The world needs a hermit in the woods as much as a preacher in the pulpit.”

There is no shame in solitude as Grainier’s mortality draws near, nor any need for regret. Soaring aloft in a biplane, he recalls Claire’s gentle counsel, and for once finds himself unshackled from time. He neither laments the past nor fears the future, but in this single, weightless moment, rather experiences the pure grace of being. In these final moments, Bentley’s historical chronicle of progress thus ends as an ode to presence, delicately marrying Train Dreams’ curatorial precision with its serene, luminous, and transcendent spirit.

Train Dreams is currently streaming on Netflix.