Noah Baumbach | 2hr 12min

Fame is a temperamental beast in Jay Kelly, yet somehow the titular Hollywood actor has thus far managed to thrive on pure charisma, effortlessly disarming fans who mistake it for authenticity. When he jumps off a train travelling through Tuscany to chase a handbag thief, it isn’t out of some innate sense of justice or morality. This effort to cast himself in the image of a movie hero is nothing more than a calculated bid for applause, and one that pays off when its footage goes viral. In light of the brawl he was drawn into a few weeks earlier with old acting school friend Tim, he is fortunate indeed that story wasn’t the one to make headlines, potentially derailing his career. He has lived a comfortable, privileged life indeed – so why does he still feel like a fraud, performing even when the cameras stop rolling?

Perhaps the answer does not lie among his entourage of loyal handlers, as selflessly devoted as they may be, nor in the smiles of adoring fans who recognise him wherever he goes. Time and space bend at Noah Baumbach’s will as Jay embarks on a journey through Italy, seeking reconnection with his daughter Daisy, yet frequently stepping back into aching memories that feel as real as the present. He was never a great father, husband, or even friend to those who played some part in his meteoric rise, inciting everyone caught in his orbit to either sever that connection or submit to its all-consuming gravity. Only now as he faces the lonely distance and crushing proximity of every relationship he has ever had does he acknowledge their hollowness, reflecting on the many crossroads of his past which he consistently met with expedient, self-serving compromise.

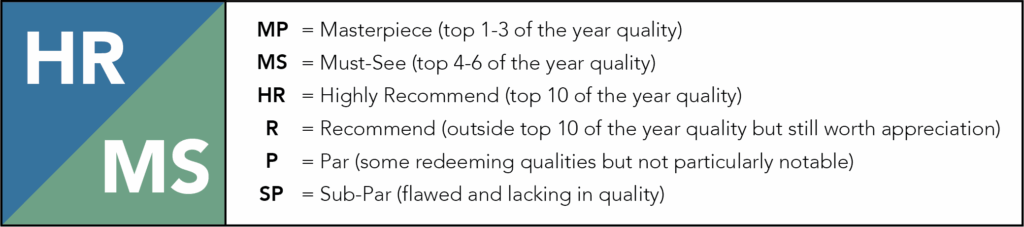

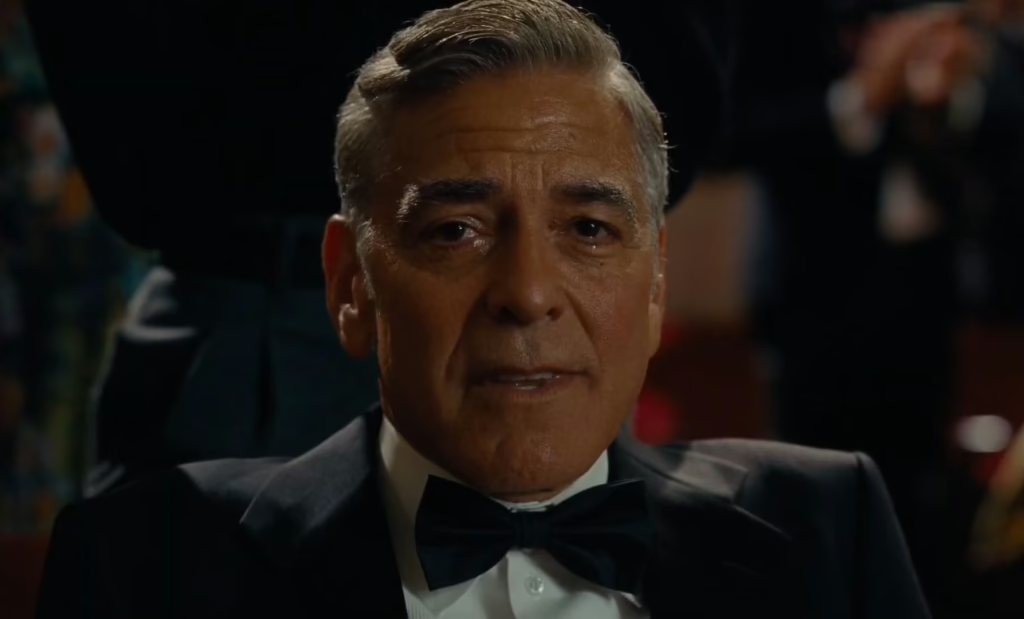

In Jay Kelly’s dreamlike elasticity, Baumbach is no doubt inspired by Federico Fellini’s cinematic odysseys through memory, fame, and debauchery, casting George Clooney in the Marcello Mastroianni roles of both La Dolce Vita and 8 ½. Where Fellini angled his self-reflexive critique of show business toward himself, here Baumbach deliberately models Jay after Clooney, whose image has long been defined by his affable everyman persona more than any radical versatility. Perhaps then Satyajit Ray’s interrogation of stardom and scandal in The Hero is the more fitting comparison, similarly charting a descent into self-doubt through a cross-country train journey and slipping seamlessly into hallucinatory flashbacks. By collapsing the boundaries between external spectacle and internal reckoning, Baumbach effectively reframes celebrity as a maze of mirrors, drawing its own architect deeper into corridors of reminiscence and self-deception until his true self vanishes among endless warped reflections.

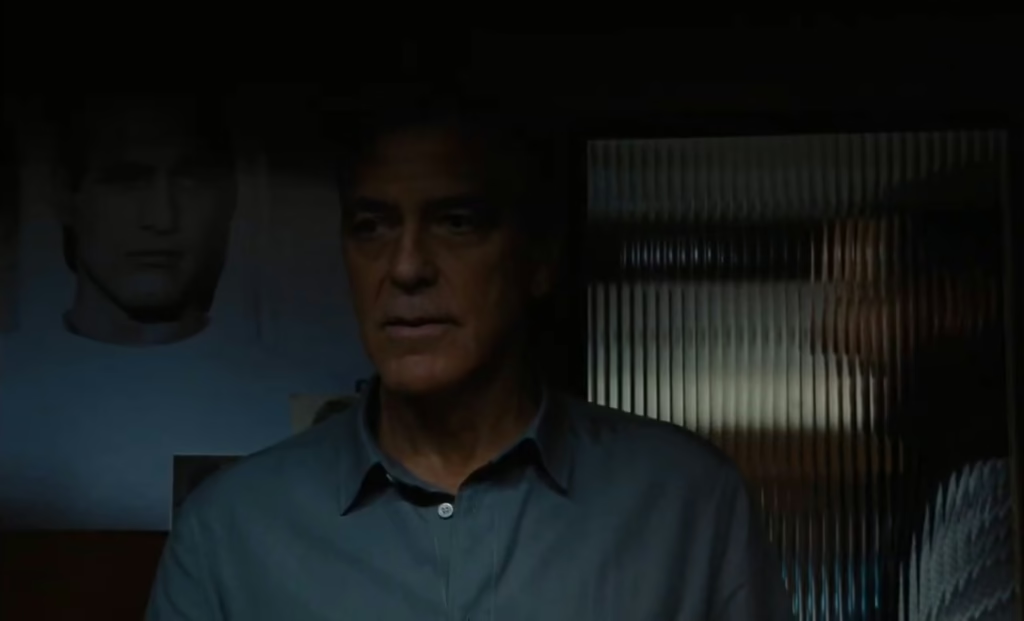

Before we step into Jay’s mind though, Baumbach first immerses us into his work, proving to be as dizzying as the dreamscapes that await. “It’s a hell of a responsibility to be yourself. It’s much easier to be somebody else, or nobody at all,” the epigraph reads, quoting Sylvia Plath, until the camera racks focus through the glass it’s etched on and settles on a dark film set. The following shot plays like a hypnotic overture, drifting through plumes of smoke and shadowed figures in a fluid long take that grazes snippets of murmured dialogue. Conversations overlap as we shift from one faceless silhouette to the next, evoking the casual chaos of Robert Altman through conversations about catering and costumes, while red, blue, and yellow lights softly break up the gloom. The camera lifts with the cinematographer’s crane into a sweeping overhead view, fluidly descends back to the cluttered stage floor, and when it frames the rain-slicked cityscape for the film’s final take, Jay is revealed leaning against a brick wall. Lit from behind by a neon Pepsi-Cola sign and bleeding from a bullet wound, he monologues on the inescapable fact of mortality, and consequently contemplates his own inevitable decline.

“I want to leave the party. In a way, I already died. I’m lucky. My time passed while I was still I alive. I got to see it end before it ended. That’s a crazy thing, when you die, everything you thought you were isn’t true.”

Not only does Baumbach blur the lines between Clooney and Jay, but Jay also admits that he often simply plays himself – though as he wryly observes, being yourself is its own difficult challenge. Clooney impresses in this self-reflexive turn, dismantling the persona that elevated him to international acclaim, and exposing a vulnerability he has rarely revealed in his leading man roles. With Adam Sandler subverting his typically manic screen presence as his manager Ron, he too wrestles with regret, though his is oriented more toward a life he traded in to serve another. Feeling as though he has been taken for granted, he stands at a critical juncture, his disillusionment revealing the collateral damage of Jay’s glittering success. Many people have been hurt by the shadow of this celebrity’s prestige, and now as he spontaneously follows Daisy to Italy in the hopes of making amends, he finds himself lost in guilty reveries more vivid than reality.

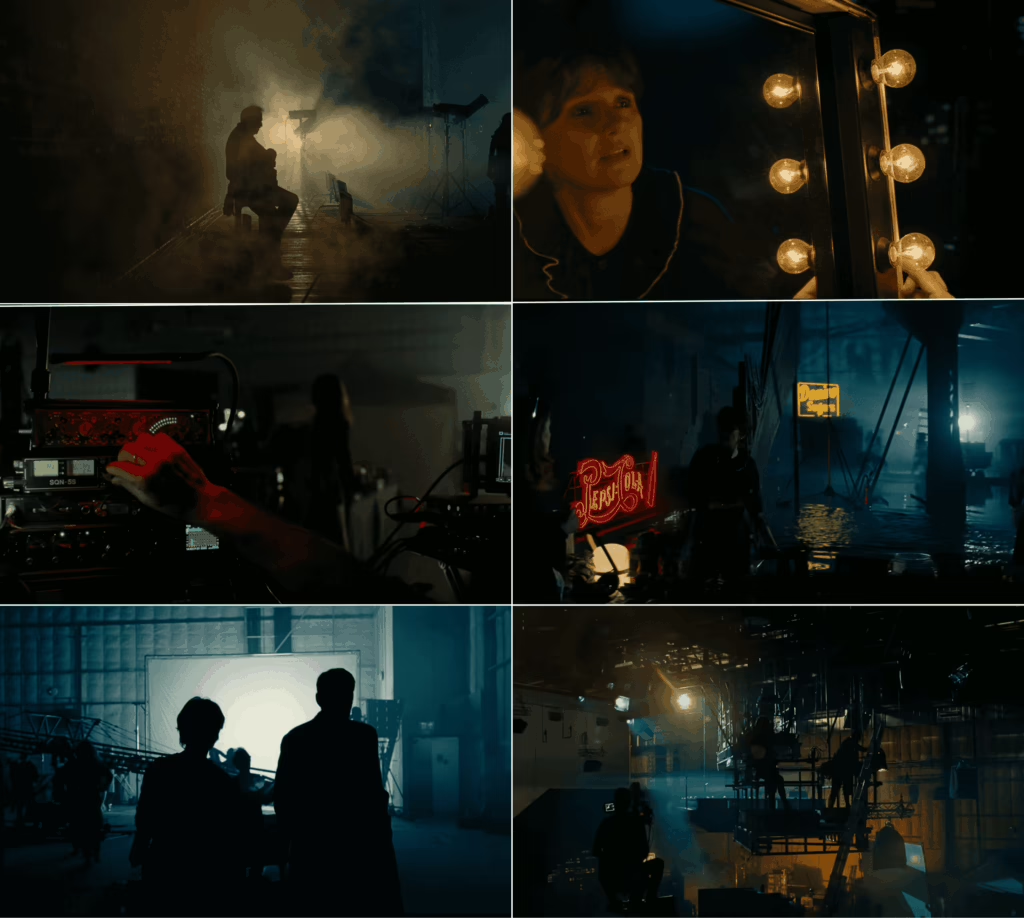

This formal conceit underpins the defining structural pillar of Jay Kelly, staging recollections as living sets where Jay is reduced to a passive spectator of his own ascendancy and unravelling. When he first learns from Ron about the passing of Peter Schneider, the director who launched his career, we follow his gaze through a window to the first flashback, as though watching an old movie spool back to life. There, he witnesses their final dinner six months prior as they call each other “pop” and “son” – yet when Peter raises a new idea for a film that might save his fading reputation, Jay is not willing to lend his name to the project. “It’s not a territory I want to explore,” he coolly rejects, refusing to take a risk for the man who once opened every door for him.

From here, Baumbach continues to dismantle these barriers between past and present even further, physically stitching together train carriages, classrooms, and film sets into one seamless continuum that Jay traverses at will. His unexpected encounter with Tim especially spurs on this self-critical reflection, as although this unrealised talent never made it in Hollywood, his method acting demonstrates far greater range and vulnerability than Jay’s polished charm. Warm nostalgia gives way to bitter contempt as Tim exhumes buried grievances, blaming Jay for stealing his job, his girlfriend, and his life, and when Tim spits personal attacks, Baumbach handsomely splits them between pools of neon blue and magenta lighting.

“Is there a person in there? Maybe you don’t actually exist.”

Later when Jay disappears into the bathroom of his private airplane and finds himself back in acting school, we observe exactly how this betrayal unfolded. Clooney’s face tightens with guilt as he watches the audition he once accompanied Tim to, and his impulsive decision to read for the same role. As it turned out, this would become his breakthrough – an effortless triumph which Jay never had to fight for, instead coasting by on confidence alone. Tim’s resentment is given sharp clarity through this flashback, and as Jay confronts the origins of his ascent, so too does his ruthless opportunism take form.

From a cramped train bathroom, an unbroken camera pan whisks us into a failed reunion with his eldest daughter Jessica, while later he wanders from a compartment into the beginning of his affair with co-star Daphne. If movies are just“pieces of time” as Peter once mused, then these fragmented memories might as well be reels of celluloid, playing in a perpetual loop with no chance of a second take. Soon enough though, even the present begins to dissolve, physically eroding the distance between Jay and Jessica on a phone call as he strolls through a blue, misty forest. Within this ethereal manifestation of his lonely mind, her tinny voice is replaced by her physical presence, conjuring an intimacy that he is beginning to accept will never be recovered with either of his daughters. Pursuing these dead relationships is evidently nothing more than a futile pilgrimage through corridors of memory.

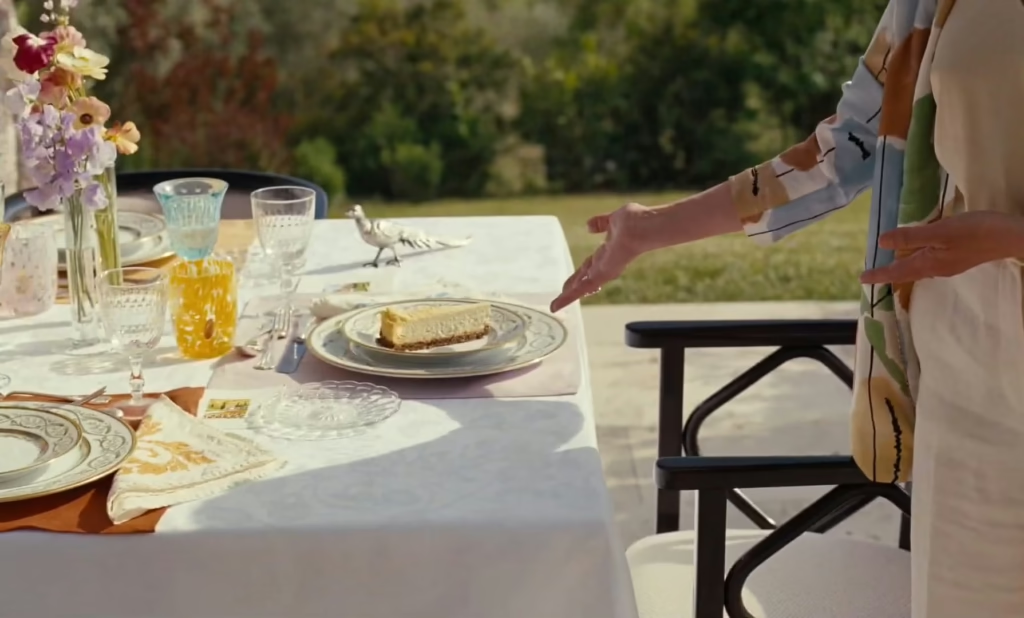

None of this is to downplay the comedy that Baumbach lightly threads through Jay Kelly, developing a wry running gag around Jay’s ritualistic servings of cheesecake and the false presumptions that it’s his favourite indulgence. This is an immensely accomplished ensemble of screen veterans and comedic talents after all, lending buoyant levity to an otherwise existential crusade, and grounding it in Clooney’s enchanting honesty. This is his self-interrogation after all, peering into an alternate life of who he might have been had he sacrificed family for sterile stardom, and expressing enormous gratitude for the people who tethered him to something real.

With Baumbach taking one more cue from 8 ½, these relationships become the emotional centrepiece of Jay Kelly’s final scene, overshadowing the montage which totally demolishes any remaining doubts as to the likeness between actor and character. This time, it is the past that rushes into the present, uniting those figures who have defined Jay’s journey. Each individual is a fragment of his life, though for once, there is the sense that even its minor players possess stories beyond his own. As Jay slips into one last dream of the past in these final minutes, Baumbach embraces unabashed sentimentality, replacing the spectacle of Hollywood with a deeply personal home video.

“Can I go again? I’d like another one,” Clooney poignantly asks at its conclusion, shattering the fourth wall with a soul-stirring gaze. Perhaps in his imagined vision of Daisy and Jessica’s backyard vaudeville show, he makes the right decision to watch rather than leave for work, but the ache of a reality without retakes persists. Memory is the only projector that Jay Kelly willingly surrenders to in his twilight years, and in its flickering images, it offers the bittersweet grace of remembering that his most authentic, imperfect scenes were the ones no camera ever captured.

Jay Kelly is currently streaming on Netflix.