Chloé Zhao | 2hr 5min

Early in Hamnet when a young William Shakespeare visits his future wife Agnes in the forest, he tells her a story. It is not one that he has composed, nor one he will write – this is the Greek myth of Orpheus and Eurydice, two lovers who tragically parted by death, and whose desperate attempt at reunion falters at the gateway to the underworld. In this dramatisation of William and Agnes’ private struggles too, doorways abound, similarly signifying that mortal threshold which separates them from their 11-year-old son, Hamnet.

At its archetypal core, the ancient legend that Shakespeare recounts is a historic expression of love and grief, resonating across millennia. Shakespeare’s plays have likewise invited countless interpretations, yet in this adaptation of Maggie O’Farrell’s revisionist novel, Chloé Zhao specifically needles in on the act of storytelling as shared catharsis. There is no reading of Hamlet more intimate than one born from the raw wound of parental loss, the film posits, and as Zhao visualises this transmutation of pain into poetry, a strange solace emerges in the theatrical ritual of reimagination.

Quiet unexpectedly though, this story does not entirely belong to the playwright whose words echo through cultural memory. Hamnet’s tale of grieving parents leans slightly towards Agnes, anchoring us to a perspective largely grounded in the pastoral rhythms of Stratford-upon-Avon, rather than the clamorous playhouses of London. The lush foliage and dappled serenity of the forest where Agnes scavenges offers soothing refuge from the strictures of village life, eventually even witnessing the birth of her first child beneath a watchful oak. While green hues breathe through the canopy and muted palettes weigh heavy back in town, Jessie Buckley’s dresses burn gently in russet shades, striking against the forest’s cool tones and dissolving into its earthy embrace. As such, she effortlessly becomes the focus of Zhao’s camera wherever it turns, filtering the same grief, love, and resilience that inspired her husband’s writing through the gaze of domestic tragedy.

Although Zhao’s dip into Marvel signalled a departure from the documentary-style realism of The Rider and Nomadland, Hamnet is evidently a far more assured evolution of her elemental style, using its period setting as a poetic backdrop to her melancholy meditations. Whether her natural light filters through canopies or glows dimly from candles, it casts an organic warmth over her characters, while authentic reconstructions of a muddy Elizabethan village mark a textural triumph of production design. Jump cuts and contemplative voiceovers further invoke the dreamlike cadence of Terrence Malick, drifting into the realm of magical realism, yet Carl Theodor Dreyer’s ascetic rigor is also equally present in Zhao’s controlled camerawork, austere minimalism, and sparse blocking of interiors.

Both these directors exert their respective influences upon her ambient aesthetic, summoning a spiritual wonder that is at once enraptured and fearful of the divine unknown. Max Richter’s heavenly score of choirs and strings serves a valuable role in amplifying its elegiac tone too, deploying the oft-recycled yet hauntingly beautiful ‘On the Nature of Daylight’ with delicate precision, and tenderly accompanying the narrative’s dips into magical realism. Zhao ushers the first of these in when Hamnet visits his ailing sister Judith one night, climbing into her bed in an attempt to trick the angel of death. “I give you my life. You shall be well,” he solemnly whispers – and indeed, whatever invisible powers are present listen to his plea. Judith is healed by the morning, but the plague begins to grip Hamnet instead, threatening to take his life as a heart-wrenching sacrifice.

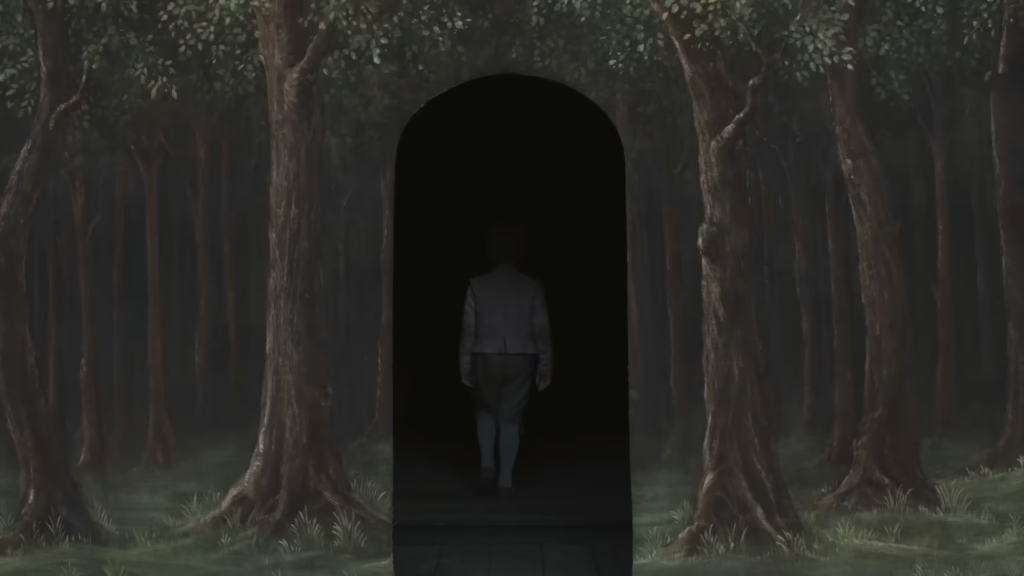

With William away in London, Agnes is left to bear the brunt of this devastation alone, and Zhao fully submits to dreamlike interludes poised on the edge of two realms. “All the world’s a stage,” Shakespeare would famously declare in As You Like It, and here this metaphor takes tangible form as we watch a dying Hamnet wander the floorboards against a painted forest backdrop. Frightened, he calls out for his mother, before turning his eyes upwards where the spirit of her hawk soars across the sky. Throughout his decline, Zhao formally weaves this hallucinatory vision, until a dark, arched doorway beckons him offstage.

It is no coincidence that this set mirrors the Globe Theatre where William stages the original production of Hamlet, named for the boy who once dreamed of treading its boards. Although Paul Mescal is absent for stretches of Hamnet, leaving Buckley to shoulder the solitude of grief with aching vulnerability, our inevitable journey to London in the final act grants him space to fully unleash William’s buried anguish. On the edge of a wharf, we witness his “To be or not to be” soliloquy emerge from unfathomable heartbreak, weighing the perilous boundary between existence and oblivion that keeps him from his son. Mescal’s theatrical background is evident in his visceral delivery of these famous lines, imbuing them with an immediacy that makes them feel less like rehearsed verse, and more like a spontaneous, unguarded confession.

Indeed, the man that Agnes once believed to be distracting himself with comedies has in fact been shaping his sorrow into dramatic tragedy – though at first glance, there is little in Hamlet’s tale of scheming kings and poisoned chalices that pays tribute to their son. One must rather look to the Danish prince’s existential introspection to discern the mournful subtext, as between him and his ghostly father, Shakespeare draws the thin veil of death. By identifying closely with the deceased and swapping their real-life roles, William frames himself as the one trapped in a spectral, guilty purgatory, wishfully letting his son take his place in the land of the living. Nevertheless, as the play draws to a close, Hamlet peacefully approaches his end before hundreds of witnesses – and his tearful, smiling mother.

“The rest is silence,” the prince utters with his final breath, and through to Zhao’s final shot, a reverent hush indeed hangs in the air. For William and Agnes, this theatre becomes a shrine to which the world pays its respects, standing at the threshold of reality and reverie where visions of their son hover between both. By sublimating sorrow into art, grief thus becomes a communal elegy, keeping this child’s spirit alive for as long as his father’s immortal words endure. Storytelling bridges impossible chasms in Hamnet, and through Zhao’s lyrical reimagining of history, its most private absences are offered tender, formal closure.

Hamnet is currently playing in cinemas.