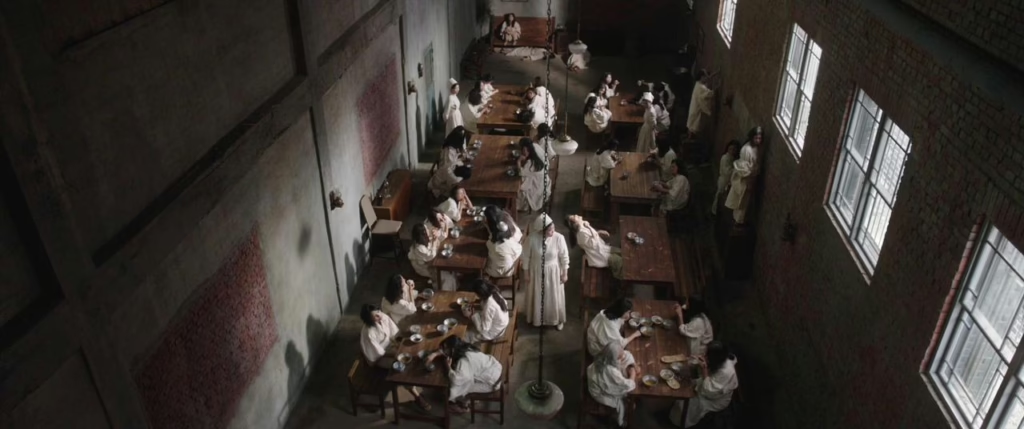

Park Chan-wook | 2hr 24min

So intricately woven are the layers of deception in The Handmaiden, that the cons masquerading as plot delicately entwine with its very structure. Subjective shifts in perspective have long been among Park Chan-wook’s greatest strengths as a storyteller, and here he invites us into a shared dramatic irony that blinds his characters to each other’s lies, yet which chooses carefully when to divulge another hidden motive. There may be a version of this tale which unfolds in linear fashion, stripped of narrative misdirection, but that would not be nearly as mesmerising as the seductive dance of concealment and revelation which Park so delicately choreographs.

By cluing us into the primary grift from the outset, we are slyly lulled into a false sense of clarity, observing the calculated manipulations of a con artist posing as Count Fujiwara and his accomplice, Sook-hee. Their target is Lady Hideko, the niece of the wealthy Korean book collector Kouzuki, who years earlier betrayed his country to Japan in exchange for a gold mine. Sook-hee is to install herself in their secluded countryside manor as a maid, guiding her mistress toward romance with the handsome nobleman when he arrives to offer painting lessons. Once married, Hideko will be committed to a madhouse, her fortune claimed. All this must of course be kept from Uncle Kouzuki, who raised Hideko with the intention of marrying her himself, yet in the meantime exploits her to lead clandestine book readings for affluent Japanese guests.

The first complication does not arrive through external interference, but from within. Not even Sook-hee counted on the possibility that she might fall for Hideko’s graceful charm, yet as she dutifully bathes and undresses her mistress, Park’s sensual camera irresistibly aligns itself with her view. Through Sook-hee’s confessional inner monologue too, we are made privy to her guilty voyeurism, even as she dutifully follows orders and nudges Hideko toward the Count. Mirrors are subtly threaded through the mise-en-scène throughout these early encounters, subtly drawing attention to the thin veil between performance and sincerity, and framing the women themselves as both the observers and observed.

By initially restricting this relationship to passing glances and lingering touches, the erotic passion that erupts one night between Seek-hoo and the heiress appears to be the first authentic expression of unguarded desire between the two women. The division drawn between them as they lie back-to-back in a gorgeously composed high angle soon dissipates when Hideko turns towards her maid, asking what men want in bed. Park’s editing grows enraptured as it euphorically throws us into Seek-hoo’s nervous role play, their tentative longing rapidly blooming into feverish intimacy, and building to an uninhibited climax.

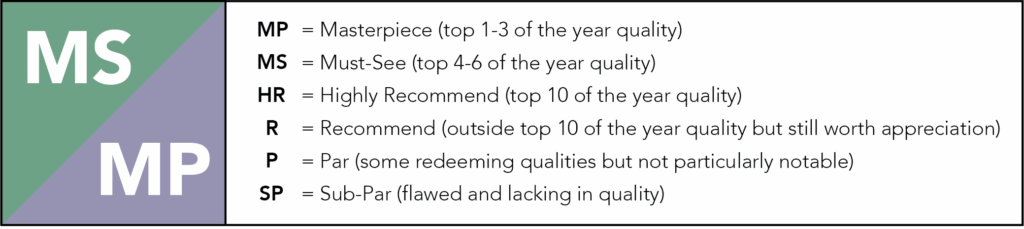

Even beyond private encounters such as these though, Park infuses The Handmaiden with a lush, visual opulence, heightening both the unspoken friction and smouldering desire that tugs at its characters’ conflicted loyalties. The camerawork is hypnotically smooth, seamlessly melding its carefully controlled tracking shots with the blocking, and elevating each character exchange into a meticulously choreographed dance. So too does it render Park’s staggeringly exquisite sets in tremendous detail, attending to every lighting fixture, shoji door, and ornate piece of furniture, where Art Deco grandeur handsomely blends with Japanese minimalism. This is 1930s Korea after all, and through such rigorously curated production design, The Handmaiden vividly captures the cultural entanglements of its oppressive, colonial history.

It is the manor’s sumptuous library of dark wood panelling and symmetrical architecture that Park establishes as the film’s most impressive set piece though, introduced through a brisk dolly shot past its rows of bookshelves, and frequently washed in melancholy shades of teal. It is there that Hideko conducts readings for Uncle Kouzuki’s guests, which, as we discover when her voiceover takes over in Part 2, happen to be of sadistic, pornographic books.

The lady of the manor is not the uncorrupted innocent that Sook-hee believed her to be, and neither is she merely a pawn in the Count’s scheme. Since childhood, she has been a victim of her uncle’s abusive grooming, becoming his performer of perverse literature after her aunt took her life in the garden. As Part 1 ends with the reveal that she and the Count have tricked Sook-hee into taking Hideko’s place in the madhouse, Park rewinds his narrative to play out the narrative thus far from the heiress’ perspetive. It is a formally ingenious move, transcending traditional notions of plot twists to fully shift the emotional centre of the film, and turning towards another performance of vulnerability.

In fact, it was Hideko’s idea from the outset to commit someone else to the madhouse in her name, thus securing the fortune while denying it to her predatory uncle. Poor Sook-hee is merely a casualty in this con, unwittingly following a path laid out by the man she believed was her accomplice. Scenes of Sook-hee and Hideko’s intimate encounters replay under dramatically altered contexts, revealing the heiress’ exploitation of her maid’s illiteracy by reading incriminating letters in plain sight, confident that this uneducated servant cannot comprehend them. The tense confrontations we previously witnessed between Sook-hee and the Count apparently weren’t so private either, as in the garden’s living arbor once thought to be a secluded refuge, we now find Hideko spying from the bushes. Just like Sook-hee, we have been fooled by a second layer of deception – yet during our time in Hideko’s mind, we also find a woman who is far more conflicted than her actions suggest.

As it turns out, not even Sook-hee’s initial account of this con was entirely truthful. Discovering authentic feelings for her unsuspecting maid, Hideko attempts to hang herself from the very tree where her aunt took her life years before. It is also there where Sook-hee finally gives in, tearfully saving her mistress’ life and thus prompting them both to come clean. With Hideko revealing the trauma of her past to a heartbroken Sook-hee, both women thus go about destroying the gilded cage of a library in which the heiress has been long imprisoned, destroying the symbol of Uncle Kouzuki’s depraved authority. As they rip out pages and cast them into a shallow pool, Park’s high angle scatters these colourful books across the floor, elegantly dismantling the aestheticised cruelty of this performative world.

With Part 1 dedicated to Sook-hee and the Count’s conspiracy, and Part 2 tracing the deceitful alliance between the Count and Hideko, Part 3 of The Handmaiden accordingly follows the third and final collaboration, forged between the women themselves. Returning to Sook-hee’s perspective and resuming the story from her abandonment at the madhouse, Park reveals the innermost layer of these schemes – their double-crossing of the Count and dash for freedom.

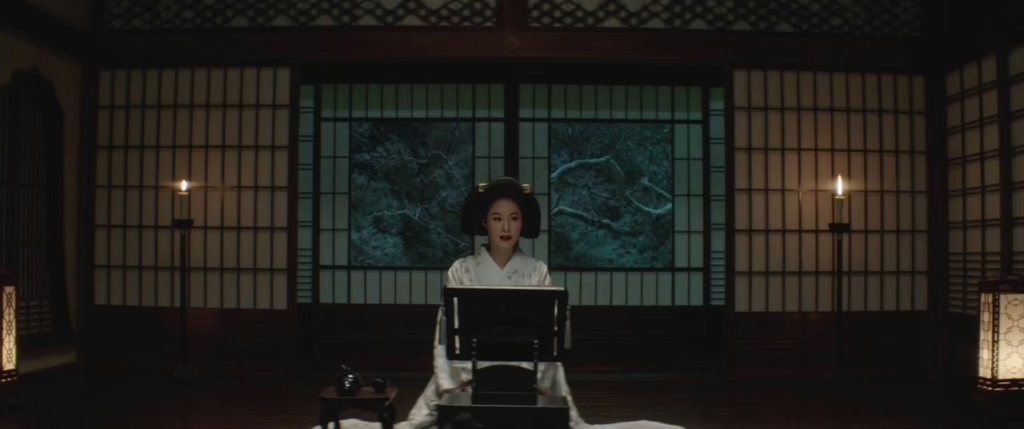

The asylum’s sterile white interiors strike a severe contrast against the cool, lush colours of the luxurious hotel where Hideko and the Count are lodged, as does Sook-hee’s contaminated rice against the city’s gourmet delicacies, though this divide is fleeting. An orchestrated fire provides the perfect cover for Sook-hee’s escape, while Hideko simultaneously carries out her side of the plan, feeding the Count opium-laced wine from her mouth under the guise of passionate kisses. Once again, sex becomes a tool of manipulation and power in The Handmaiden, deepening the sting of betrayal with each calculated touch.

Park is not yet done reframing scenes we have already witnessed though. Captured, unmasked, and returned to an infuriated Uncle Kouzuki’s manor, the Count is physically tortured, and forced to recount the night that he and Hideko consummated their marriage in disturbing detail. His voiceover may tell one story of a “ferocious wedding night”, but the flashback tells another, revealing Hideko’s taunting self-pleasure and simulation of her lost virginity. Granted a light for his cigarette, the Count pulls out one final, sinister trick from his arsenal, filling the room with the ethereal blue haze of mercury vapour and condemning them both to death.

Escaping Kouzuki’s clutches and sailing away beneath a pink, cloudy sky, these women are finally granted reprieve from the traps and lies that once bound them to roles written by men, and so too are we graciously released from Park’s own labyrinth of illusions. He has held us firmly in his grasp, guiding our emotions and allegiances with the same precision as his characters, yet also moves us with a disarming sincerity that transcends artifice. Sex is reclaimed as an act of defiant trust, and through this vulnerable connection, The Handmaiden deftly executes its most daring gambit – transforming deceit into a vessel of intimate, unflinching authenticity.

The Handmaiden is currently available to rent or buy on Apple TV, YouTube, and Amazon Video.

MS/MP ? I honestly don’t see what the Handmaiden lacks to be considered a MP tier film. You don’t bring up any flaws here so I’d assume it’s not that. I mean the movie’s beginning to end energetically directed, with formal elements that enhance the narrative constantly present in the mise en scene, and the three act repeated perspective shift is absolutely brilliant. It’s not a major 2010’s masterpiece , it’s no La La Land or The Revenant, it’s not even an Inside Leywin davis tbh, but I couldn’t see it being below the top 30 of the 2010’s. I don’t see how Parasite is a tier above it for example, Parasite’s screenplay has more detail, but it’s not as visually striking or as energetically directed. I know I sound like I’m just complaining about why a film I like isn’t rated higher, but I’m genuinely curious on what the difference for a MP and a MS/MP film is for you.

I don’t think I have a great answer for you. It’s not so much about any inherent flaws than parts of the film that I feel I didn’t fully grasp the first-time, specifically around Hideko’s backstory. To be honest, this has often been my problem with Park’s films – they’re so layered that I have underrated virtually every single one of his films on a first watch and upgraded them on rewatches. The argument for it as an MP is strong, so I wouldn’t be surprised if it’s the same here.