Pier Paolo Pasolini | 1hr 57min

This review discusses extreme depictions of sexual violence, torture, and fascist cruelty as presented in Pier Paolo Pasolini’s Salò, or the 120 Days of Sodom. It contains descriptions of rape, bodily fluids, execution, and graphic acts of physical and psychological abuse. Reader discretion is strongly advised.

To Pier Paolo Pasolini, disgust is among the strongest of human emotions, and one that is rarely used to its fullest potential in cinema. It triggers physiological reflexes deep in our gut, implanting visceral reminders of that which threatens the foundations of our personal safety. On this basis, the vile horror of Salò, or the 120 Days of Sodom discomfortingly succeeds. Revulsion is primally invoked in its depiction of forced sexual acts involving bodily fluids, as well as the bloody torture and execution of teenagers, each subjected to the sadistic games of four wealthy men who have taken them prisoner.

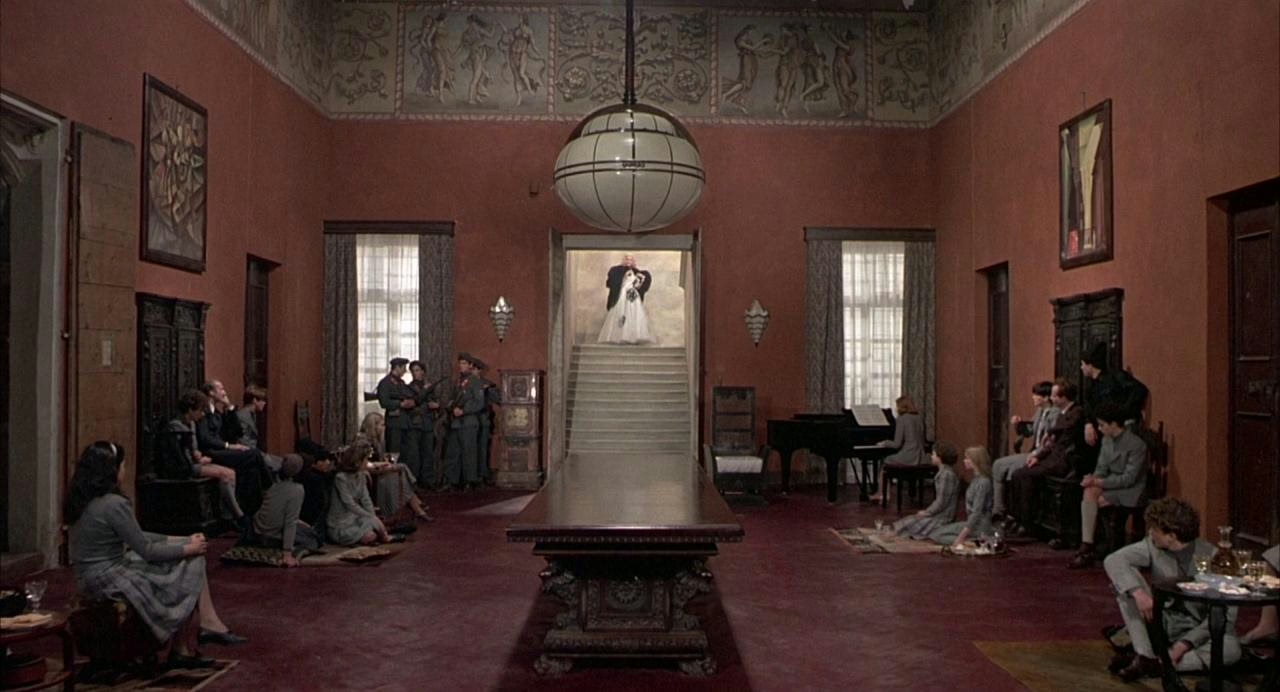

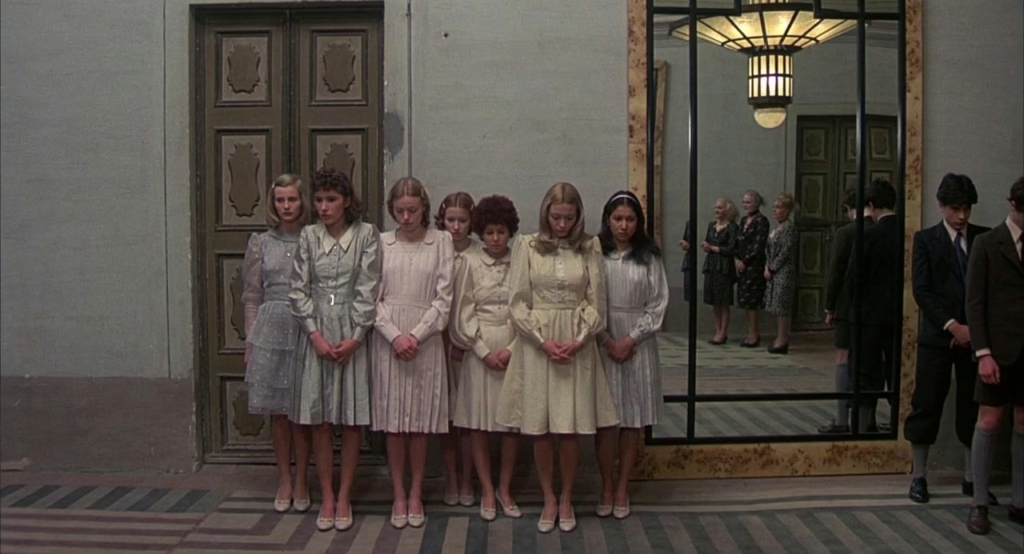

That Pasolini situates these grotesque punishments within a lavish Italian villa of ornate furniture and classical art sets an immediately jarring contrast, implicating beauty itself in the atrocity at hand. Virtue decays beneath cold, polished surfaces, masked by the grandeur of high culture, and casting the dehumanisation of innocence in a sterile gleam. If anything in this world is deserving of our abhorrence, then it is this, Pasolini posits – a nauseating vision of systematic fascism at its most malevolent. Hell is not fire and brimstone in Salò, but a hermetically sealed world of imperious elegance and institutional abuse.

Drawing on the 18th century novel The 120 Days of Sodom, Pasolini specifically directs the Marquis de Sade’s incendiary critique of corrupt authority toward Nazi-occupied Italy and its violent pillars of power. The Duke, the Bishop, the Magistrate, and the President are the four libertines who assert their will as the only legality here, each an archetype of social influence – the aristocracy, the clergy, the law, and the government. Accompanying them are four collaborators who serve as guards, and four ‘studs’ who partake in the debauchery, all of them adolescent boys. As if to hold up a gendered mirror, so too do the libertines take each other’s daughters in marriage, and find company in four middle-aged prostitutes who adopt the role of storytellers. Finally, Pasolini weaves this recurring number into the very structure of Salò, referencing Dante’s Inferno with an introduction labelled ‘Ante Inferno’ before descending through chapters titled ‘Circle of Manias’, ‘Circle of Shit’, and ‘Circle of Blood’.

Few films are carved with a formal rigour as exacting as this, imposing clinical discipline upon humanity’s feral appetites and shaping chaos into tyrannical ceremony. It is a satire in only the starkest sense, tempting laughter at these libertines’ absurd self-debasement, yet consistently eclipsing it with graphic depictions of rape, murder, and sexual degradation. Their theatrical irreverence does not negate their capacity for harm, and as we see in the collaborators who turn on their peers to secure favour, those who comply risk similarly damaging themselves. This is the true face of modern-day totalitarianism, as presented by Salò – not so much a regime of brute force than one of ritualistic cruelty and gratuitous spectacle.

Of course, Pasolini’s transgressive achievement would not be nearly as towering were it not for his painstakingly crafted compositions, often mimicking Renaissance paintings in their symmetrical tableaux, linear perspective, and geometric architecture. Likewise, Art Deco and Bauhaus-inspired styles lend these regal halls of power a cold modernity, specifically anchoring Salò’s setting to the recent history of World War II and casting the horrors of fascism in a disturbingly familiar frame.

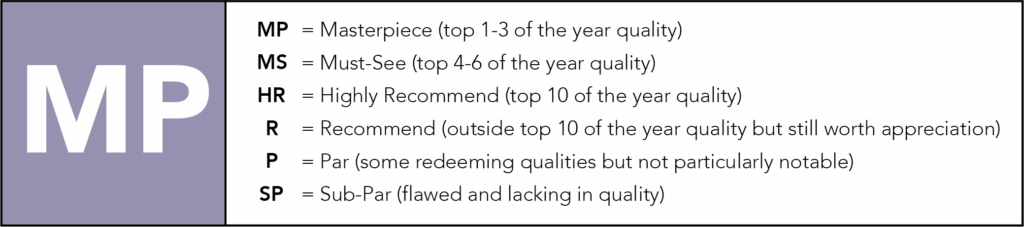

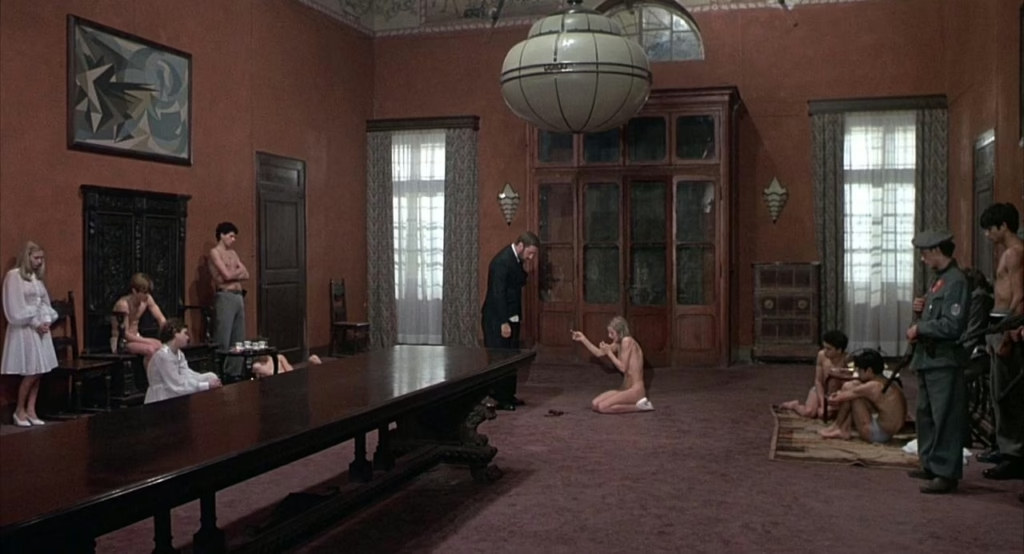

Pasolini’s blocking of actors in this space similarly conforms to these refined aesthetics, yet in his choreographed brutality, he explicitly profanes the classical order. His art does not strive to celebrate the human form, as Leonardo Da Vinci did centuries prior, but to expose its desecration at the hands of authoritarian control. Where the libertines wear fine clothing and lounge across furniture like the noble subjects of oil paintings, the enslaved teenagers are dressed in austere grey uniforms and eventually stripped entirely. Their rightful place is on the floor, thoroughly objectified by the libertines’ exercises in physical and psychological torture, and stripped of individual identities when their rulers play their most repugnant game of all.

“I think there is a way to repeat the act of the executioner,” the Bishop ponders, challenging the Duke’s argument that murder as a form of abuse cannot be repeated upon the same subject. Gathering their young victims in a single room and instructing them to kneel with their backsides in their air, they thus hold a contest – whoever possesses the “prettiest” posterior is to be killed. There is no distinguishing between male and female in this foul commodification of bodies, arranged like offerings on an altar. When the libertines eventually choose the winner and hold him at gunpoint, the empty click of the barrel briefly relieves tension – until the Bishop explains his method of perpetual execution.

“You poor idiot. You must be stupid to think death would be so easy. Don’t you know that we intend to kill you a thousand times over? Until the end of eternity – if there could be an end to eternity.”

By further desecrating the holy institution of marriage too, these fascists essentially lock the adolescents in a conjugal prison, performing mock weddings to pervert this traditional rite of passage into a shattering loss of innocence. Pasolini continues to approach his staging with aesthetic rigidity here, particularly when the libertines themselves decide to marry their studs in a blasphemous parody of matrimony – the Duke, Magistrate, and President garbed in drag, while the Bishop conducts the ceremony in searing red robes. Within the otherwise colourless hall, these aggressive tones pierce the grim proceedings, drawing our eye to the farce of power dressed in sacred vestments.

The end goal of all this is apparent. By crushing the human spirit and everything it reveres, the regime compels its victims to turn on one another, ensuring that the machinery of violence sustains itself through internal collapse. Seeking favour with the Bishop, one boy betrays a girl’s secret photograph hidden under her pillow, and she in turn informs on the guard Ezio’s forbidden liaison with a servant. In what is perhaps Salò’s most unexpected act of rebellion though, Ezio meets the firing squad with an upraised fist, and dies a forgotten martyr in wordless, Communist defiance.

As for the others who have been deemed rule breakers – they are granted nothing more than slow, agonising deaths. From the upper floor of the villa, we adopt the President’s voyeuristic gaze, peering at the medieval carnage outside through binoculars. There, they are raped, hanged, scalped, whipped, and branded with hot iron. They have their eyes gouged out, their genitals held to open flames, their necks crushed, and their tongues sawn off. At the very least, we are mercifully granted silent reprieve from the sound of inhuman suffering, though this does little to temper the sheer horror on display. It is no wonder that Salò holds the reputation it does – this is an extraordinarily tough film to stomach, stripping away the comforts of narrative to confront the ease with which cruelty may be systemised and aestheticised.

Perhaps then it is surprising to learn that behind the scenes of this impassioned political diatribe, the cast reported largely positive experiences, even spending their free time playing soccer against the crew of Bernardo Bertolucci’s epic 1900. Not so blithely innocent is Pasolini’s devastating murder three weeks before Salò’s release, officially sealing it as his final work and denying him the macabre pleasure of witnessing its polarising reception. Even as we admire the film’s cinematic audacity, it’s hard not to sympathise a little with its detractors, though whatever revulsion is provoked by such brutal imagery pales in comparison to the outrage warranted by real-world fascist regimes that institutionalise these atrocities. In truth, turning away does nothing to erase their existence. Through his uncompromising lens and formal severity, Pasolini stares unflinchingly into the repellent darkness of humanity’s soul – and if we are to understand the depths of our own enduring, moral complicity, then so too must we.

Salò, or the 120 Days of Sodom is not currently streaming in Australia.